On Nietzsche Mountain

“They don’t go to Nietzsche to reflect on or question themselves, but to confirm their beliefs.”

DECEMBER 5, 2024

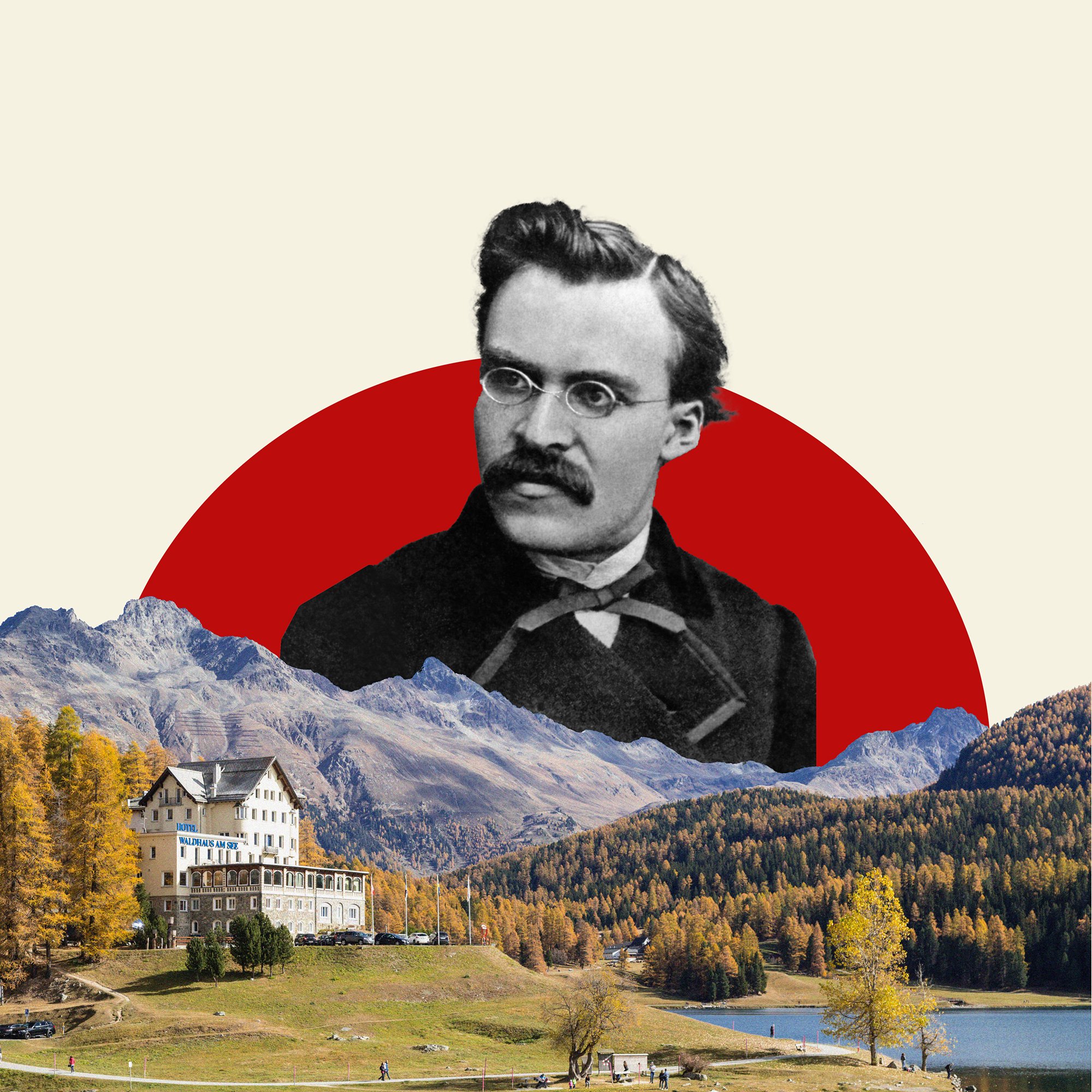

Every year, people gather in a luxury hotel perched above Sils Maria, a small village in the Swiss Alps, to discuss the life and work of Friedrich Nietzsche. This year, I was among the 50 or so guests who came together at the Waldhaus Hotel to listen to lectures, go on walks, debate and drink wine.

The topic of this year’s conference was Ecce Homo, Nietzsche’s last work, written before he collapsed into madness and published posthumously in 1908. It is an unusual text, a quasi-biography that discusses his life and the creation of his works. Chapters are headed “Why I am so wise,” “Why I am so clever,” “Why I write such excellent books.” It seems to contain signs of the oncoming breakdown.

The Nietzsche Colloquium typically takes place over four days at the Waldhaus. The first day began at 4 p.m. in the great hall of the hotel. We sat in comfortable velvet seats, beside large glass windows that look out over the valley. A trio played live music. More guests were over 50 than under, and there were nearly as many women as men. The majority were staying at the five-star hotel. They would dine together every night, a set menu with many courses. Others were staying in the town of Sils Maria and would be left to their own devices in the evenings. (I stayed a few villages away). This year, there were lectures by Swiss, German and Italian academics, as well as by one American, exploring some facet or interpretation of Ecce Homo. Each lecture was followed by a debate. Guests could also sign up for reading groups, to discuss Nietzsche’s texts in more depth. For most of the guests, the event was a yearly pilgrimage, an opportunity to mingle with academics and intellectuals in an idyllic setting.

Besides the luxurious hotel, the big draw is, of course, the promise of new insight into one of the most influential, and controversial, modern philosophers. Nietzsche, who famously proclaimed that “God is dead,” was a powerful critic of traditional conceptions of morality, religion and philosophy. Arguing that society held a false understanding of “good” or “bad,” he undertook a “revaluation of values.” His thinking was full of contradictions, and he made a point of accepting them. He championed the idea that there is no one absolute truth and that knowledge is always based on perspective. Crucially, he claimed that all people are driven by a “will to power” — the idea that there is not only an instinct to survive but to thrive.

His ideas made an indelible mark on 20th-century theology, psychology and philosophy, influencing thinkers like Sigmund Freud, Albert Camus and Michael Foucault. They also have a darker legacy. After Nietzsche’s death, his sister Elisabeth, who was married to a virulent antisemitic activist and who would later support Adolf Hitler, took control of his literary estate. Among other posthumous works, including Ecce Homo, she published a book titled The Will to Power that took fragments of Nietzsche’s work and pasted them together in service of her own ideas. Nazi propagandists went on to misuse phrases like “Übermensch” and “the blond beast” to justify their ideas of a racial hierarchy.

Besides the luxurious hotel, the big draw is, of course, the promise of new insight into one of the most influential, and controversial, modern philosophers.

At the conference, though, there was no mention of how Nietzsche’s ideas were coopted by the Nazis, or why his philosophy continues to find traction among today’s alt-right. This unpalatable aspect of his legacy was, it seemed, considered out of place in the tasteful, hushed atmosphere of the Waldhaus Hotel. For many people Nietzsche is simply whoever they want him to be.

✺

Nietzsche was born in 1844 in the Prussian province of Saxony. His father and younger brother died when he was five and he grew up with his sister, mother, grandmother and two aunts. He was smart and could debate his classmates in Latin. He started and then stopped studying theology, turning to philology instead, a subject in which he became the youngest ever professor at Basel, when he was only 24.

Ten years later, he left the post and wandered around Europe on his pension, not settling anywhere. He suffered from chronic headaches, terrible eyesight and debilitating stomach pain, which he treated with all sorts of tinctures, opioids and acids. The search for a place with a climate suited to his illnesses led him around Europe: He spent time in Nice, Genoa and Turin, and in 1881 discovered Sils Maria, where he would return every summer for seven years.

His many published works were not successful — some sold no more than 100 copies. Yet he was convinced that he would be recognized by later generations. In 1888 he wrote four books, including Ecce Homo, while he was residing in Sils Maria and then Turin. In January 1889, he had a breakdown. He spent the next three days singing, crying, dancing naked and sending letters to friends and family of such a concerning nature that his friend Franz Overbeck went immediately to Turin to pick him up. He was admitted into a mental institution, and around this time people started to express interest in his work. Nietzsche’s publisher decided to reprint his books, which so far had been gathering dust on the shelves, and they began to sell.

Why the sudden popularity? The German philosopher Rüdiger Safranski has a theory: Nietzsche’s descent into madness leant his work new allure because it suggested he had uncovered something so deeply true and unsettling about humanity that it drove him insane, Safranski wrote in his 2000 biography of Nietzsche.

✺

The Waldhaus Hotel was not around when Nietzsche was alive. It opened in 1908, the same year Ecce Homo was published, eight years after his death. When he came to Sils Maria, he stayed in the village itself, in a simple room in a simple house. A visit to this house, which has been renamed the Nietzsche House and turned into a small museum about the philosopher and his time in Sils Maria, is part of the colloquium’s agenda every year.

The nature surrounding the town is beautiful in the superlative: rough mountain tops against blue sky, moody dark forests lining milky-blue lakes and a cloud formation named the “Maloja Snake,” which slithers through the valley almost every day. Intellectuals and artists, including Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke and Alberto Giacometti, came here to be inspired. It was easy to see why.

One philosophy student, who was there for the third time, complained that Nietzsche, because of his high regard for the aristocracy, seemed to attract people who have money.

On the first day of the conference, after a drinks reception and the first lecture, we examined one of only seven remaining copies of Thus spoke Zarathustra 4 that Nietzsche printed himself. We were invited to carefully touch the thin book and to notice Nietzsche’s handwriting on the blue cover page. In another box lay a first edition of German scholar Oscar Levy’s English translation of Ecce Homo, published in 1910. Levy’s granddaughter, Julia Rosenthal, told us the story of how Levy fled Germany and its antisemitism in the 1890s for England, where he became a Nietzsche scholar. After dinner, we reconvened for another lecture — this one on the question of self-criticism according to Nietzsche.

One of only seven remaining copies of Thus spoke Zarathustra 4 that Nietzsche printed himself. Guests of the Nietzsche Colloquium were invited to carefully touch the book and examine the philosopher's handwriting on the title page. (Photo by Tania Roettger)

The cloud formation called “Maloja Snake” as seen through the window in the Waldhaus. (Photo by Tania Roettger)

When he came to Sils Maria, Nietzsche stayed in a simple room in a simple house. A visit to this house, which has been turned into a small museum, is part of the colloquium’s agenda every year. (Photo by Tania Roettger)

The next day, we toured the Nietzsche House. A permanent exhibit presented the philosopher’s famous fans from the last century — among them the Romanian-born French poet Paul Celan and the Russian writer Boris Pasternak. There was also a tribute to Mazzino Montinari, the Italian communist editor who founded the Nietzsche Colloquium in 1978. Back then, the event was still held in the Nietzsche House, and the few attendees would sleep in the guest rooms. Montinari would come down the creaking stairs in the morning to smoke a cigarette as young Nietzsche scholars quizzed him in the same kitchen where Nietzsche had once eaten. At night they, too, drank wine and debated philosophy. Today, a photograph of Montinari standing outside the house, cigarette in hand, hangs on the wall. Here, people are not just fans of Nietzsche, but fans of his fans.

The colloquium “is always enlightening,” a woman in her 50s, who has attended 10 of these events, told me. It is the highlight of her year. There’s just something about being around educated people, and the atmosphere of the hotel, she said.

One philosophy student, who was there for the third time, complained that Nietzsche, because of his high regard for the aristocracy, seemed to attract people who have money. “They don’t go to Nietzsche to reflect on or question themselves, but to confirm their beliefs.” But the student added that true Nietzscheans — people who believe in him like a prophet — also sometimes attend. Last year, a guest went on stage and got down on all fours to demonstrate the Über-Tier — the idea, which Nietzsche mentions only briefly in Human, all too Human (1878), that people believe they are the most supreme animal. The bizarre performance showed how seriously some people take Nietzsche here, the student said.

A handful of guests were attending the conference for the first time. I met a woman who fell in love with Nietzsche when she read Beyond Good and Evil (1886) at 16 and went on to study philosophy as an undergraduate. Another guest said he had recently retired and enrolled in a university philosophy course; over the next four days, he was hoping to deepen what he had learned about Nietzsche in his first seminar. One woman had stumbled into the colloquium by chance; she was in the area to hike, but the weather was bad.

A group of students, attending the lectures as part of a seminar at the University of Basel, told me they were having a hard time following. I knew what they meant. Some of the lectures were highly technical, assuming more than a little prior knowledge. A few were also overly formal: In one, a professor in elegant clothes analyzed an excerpt containing some of the sillier-sounding terminology in Nietzsche’s writing (such as the “Hanswurst,” literally “Hans sausage,” often translated as buffoon) in a monotonous voice that made for a odd contrast between the lecture and its subject. By the end, the lecturer had argued that the term was in fact a meaningful one, used by Nietzsche to describe not only a buffoon who struggles to come to grips with modern ideas, but also the unconscious buffoon who does not question his own pathos.

✺

Deciphering Nietzsche is like learning a secret language. His prose veers wildly from judgments full of disgust to wonder at the beauty of the world (he describes a day in Switzerland’s Upper Engadine, the region that includes Sils Maria, as “containing within itself all opposites, all gradations between ice and south”). He is also known to conjure up vivid images to convey abstract ideas. In Ecce Homo, when he talks about a previous work, Twilight of the Idols, whose hypothesis is that “the old truth is coming to an end,” he writes: “A great wind blows through the trees, and all around fruits drop down — truths.” Sometimes he sounds like a disgruntled newspaper columnist (“The English diet too … is profoundly at odds with my own instinct; it seems to me that it gives the spirit heavy feet — the feet of Englishwomen…”); other times, like a writer of mystical fairytales (“We have an as yet undiscovered land ahead of us, whose borders no man has yet descried, a land beyond all previous lands and corners of the ideal, a world so over-rich in what is beautiful, alien, questionable, terrible and divine”). His grasp of language and unexpected turns of phrase made him one of the most read, quoted and debated philosophers of the past century. In 1932, the German writer Kurt Tucholsky quipped: “Tell me what you need, and I’ll get you a Nietzsche quote for that.”

Deciphering Nietzsche is like learning a secret language.

Nietzsche also contained contradictions. He railed against religion, but the titular character of his Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a religious figure, and Ecce Homo is full of biblical references. He wrote things like, “When a woman has scholarly inclinations there is usually something wrong with her sexuality,” but was friends with smart and outspoken women, such as the Russian writer Lou Andreas-Salomé and composer and pianist Cosima Wagner.

Ecce Homo further complicates attempts to understand who Nietzsche really was. In it, Nietzsche portrays himself as healthy even though he was ill. He claims he is Polish even though he was German. He makes himself out as successful even though objectively he was not. He writes about glowing friendships even though he was isolated. In one of the colloquium’s most well-received lectures, Anthony Jensen, a professor from Providence College who is on the editorial board of Walter de Gruyter’s Nietzsche scholarship series and was previously an associate editor of The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, suggested that this was not a sign of madness but an attempt to rewrite his failures and to heal.

✺

None of the lectures at the colloquium directly addressed the more controversial aspects of Nietzsche’s work. A few years ago, a returning guest told me, a lecturer gave a feminist reading of Nietzsche’s writing about women, arguing that what he wrote in later years was misogynistic. But this did not go down well with some of the colloquium guests.

“You can find anything in Nietzsche — for democracy, against democracy. Anyone can read their own opinion into him.”

I asked whether Nietzsche’s adulation in some corners of the far right was ever discussed at the colloquium. No one had ever lectured on such a thing, as far as anyone could recall. Instead, everyone I spoke to reiterated that Nietzsche himself was against nationalism and antisemitism.

“The idea of ethnic purity does not exist with Nietzsche,” said Hubert Thüring, a professor at Basel and publisher of Nietzsche’s work, as well as the colloquium’s program coordinator. It was the third day of the event, and we were sitting in a corner of the great hall, where several guests were reading. A group of attendees who obviously belonged to the far right had attended the colloquium once, in the 1980s, he told me. Perhaps to stake out whether there was something here for them. They did not come back.

“There is no philosophically sound reading of Nietzsche as right-wing,” Jensen, the professor from Providence College, agreed. But he added: “You can find anything in Nietzsche — for democracy, against democracy. Anyone can read their own opinion into him.”

Members of the German far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD) reference Nietzsche frequently, as do prominent figures of the white nationalist movement in the United States. The right-wing influencer “Bronze Age Pervert,” who preaches fitness and diet as a means to dominance, has recorded several podcast episodes on Nietzsche.

“The only right interpretation is the direct, explicit and naïve one that Nietzsche is a right-winger, a man of the far right,” he tells listeners about Ecce Homo, in an episode from March 2021. He quotes passages from Nietzsche’s writing on nutrition and exercise, such as: “Sit as little as possible, give no credence to any thought that was not born outdoors, as one moved about freely, in which the muscles are celebrating a feast as well.” Bronze Age Pervert also claims Nietzsche as his “spiritual father,” noting that the philosopher went on long walks and carried books on his travels (which the podcaster compares to weightlifting). He warns that listeners “should never read any academics about him … only his original words” and even speculates about Nietzsche’s corpse: “Medical students who witnessed his autopsy say he was ripped!” (Nietzsche did not get an autopsy. Toward the end of his life, he could neither walk nor stand.)

✺

On the last day of the conference, the sun was shining, and a cold wind blew from the Maloja mountain pass. The organizers announced the date for next year’s event. The topic, they said, would be “Justice and Violence.”

After the conference concludes, the path to the peninsula in the Sils lake is busy with wanderers. Among them, several from the colloquium, who are taking these final moments to walk the path that Nietzsche himself walked.

I wondered what Nietzsche would make of us attempting to follow in his footsteps. In his foreword to Ecce Homo, Nietzsche wrote in 1888: “I need only to talk with one or other of the ‘educated people’ who come to the Upper Engadine in the summer to convince myself that I am not alive.”

I asked Wolfram Groddek, a professor from Zurich who gave the first lecture of the colloquium, an introduction to the pleasure of reading Nietzsche, what Nietzsche meant by this.

“It means he had no success,” he told me. “The educated people did not understand him.”

IMAGE: Illustration using photos of the Waldhaus Hotel and Lake St. Moritz and Nietzsche (c. 1869) (via Wikimedia)