Emergency Mode in Geneva

President Donald Trump’s cuts to USAID have thrown the “capital of international development” into disarray.

FEBRUARY 13, 2025

State of the World features occasional dispatches on the latest news, events, and ideas. To receive these updates directly in your inbox, sign up for our newsletter.

✺

This week, Isabelle Mayault reports from Geneva, Switzerland.

One of the signs at the main entrance to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) offices in Washington, D.C. being taped over on February 7, 2025. (By G. Edward Johnson via Wikimedia)

On January 24, WhatsApp groups buzzed all night with three strange words: “stop work orders.” The buzz came from a leaked memo signed by the State Department Director for Foreign Assistance Peter Marocco, which went viral across Geneva’s ecosystem of international organizations and NGOs. “For existing foreign assistance rewards,” the memo said, “contracting officers and grant officers shall immediately issue stop work orders.” Not unlike the word “lockdown” early in the COVID pandemic, the phrase “stop work orders” felt at first both threatening and vague; it would take on a more ominous meaning in the days ahead.

Geneva is a city built in part thanks to international aid money. One of the city’s most recognizable landmarks is the United Nations headquarters, which looms large behind four rows of flags. A giant red sculpture at the center of the city known as the “Broken Chair” symbolizes opposition to landmines and cluster bombs. The city is home to 43 major international organizations and 750 non- governmental ones; the headquarters of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR) are roughly a mile apart. Some 32,000 international civil servants and NGO workers bring with them conversations in global English, sky-rocketing real estate prices and expensive bilingual private schools.

By now, Geneva, a usually sleepy city during the winter, was in fully emergency mode.

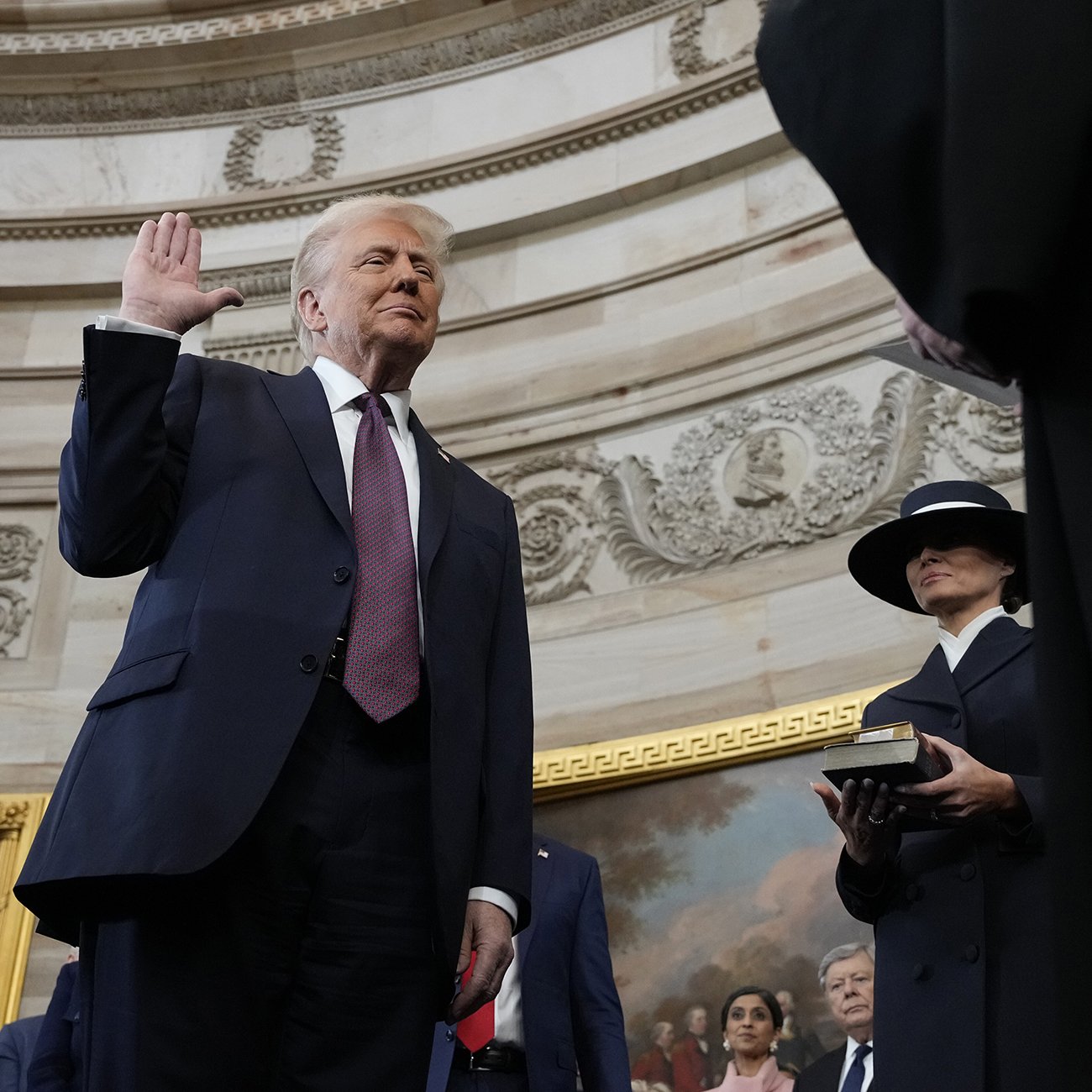

Things didn’t look too good for Geneva when Donald Trump was elected, but at first, most remained unfazed. Hadn’t Trump tried to quit the WHO in July 2020 and failed? Hours after taking office on January 20, Trump had ordered a 90-day pause in all foreign aid — with an exception for funding for Israel and Egypt — pending an internal review. But wasn’t it possible, or even likely, that he would change his mind if the news caused a big enough stir?

By late January, the consequences of Trump’s second term were clear.

Three days after Marocco’s memo, 60 top executives from U.S.A.I.D. were put on leave, leaving the international community in Geneva asking: Who would assess the pending contracts they so existentially depended on? A day later, on January 28, newly appointed Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a waiver making a second, broader exception for life-saving humanitarian assistance. The waiver had some in Geneva hoping for the best. But a week later, Rubio announced that he was now the administrator of the formerly independent U.S.A.I.D. agency; he and the State Department would be in charge of the review.

By now, Geneva, a usually sleepy city during the winter, was in fully emergency mode. Ken Jackson, assistant to the administrator for management and resources at U.S.A.I.D., issued another memo threatening employees who might be tempted not to comply with the new orders. “Failure to abide by this directive, or any of the directives sent out earlier this week or in the coming weeks will result in disciplinary action,” said the memo, written in the flat and aggressive style characteristic of the administration’s prose. By then, it was clear to anyone working in sectors dependent on U.S. foreign aid that it wasn’t just going to be a bad week, but bad weeks, perhaps even months.

Some 32,000 people in Geneva work in sectors funded heavily or in part by U.S. foreign aid. U.S. money makes up 18 percent of the WHO’s budget and 40 percent of the UNHCR’s. Thousands of contracts won’t be renewed in the next few months.

The U.S. is the biggest donor of foreign aid in the world. Now, $71.9 billion (the U.S. contribution in 2023) were suddenly gone. According to ForeignAssistance.gov, 27 percent of this amount was used for economic development, 21.7 percent for humanitarian assistance and 22.3 percent for health. More than half of the total — $43.8 billion — was disbursed by U.S.A.I.D. “I don’t think in the entire history of humanitarian assistance we’ve ever seen a shutdown of this size by any government,” said Peter Bouckaert, the former head of emergency for Human Rights Watch, now based in Madagascar. “Things have [come] to a halt. It is absolutely unprecedented.” Terre des hommes, the largest Swiss NGO dedicated to childcare, issued a statement saying 130,000 children around the world risked being affected by these cuts. In Bangladesh, the NGO said, 47,000 Rohingya refugees may be deprived of access to drinkable water. The Norwegian Refugee Council, whose Internal Displacement Monitoring Center is based in Geneva, said it was forced to “halt the scheduled February distribution of emergency support to 57,000 people in communities along the frontlines” in Ukraine.

Some 32,000 people in Geneva work in sectors funded heavily or in part by U.S. foreign aid. U.S. money makes up 18 percent of the WHO’s budget and 40 percent of the UNHCR’s. Thousands of work contracts won’t be renewed in the next few months. “Many of the contracts we have at the U.N. are precarious,” said one employee, speaking on the condition of anonymity, suggesting that these short- term contracts would be easy to terminate.

U.N. agencies refused to openly break into panic. The WHO, which used to hold a daily press conference during the pandemic, told me over email that no such conference was on the agenda to discuss the recent U.S. announcement. The UNHCR issued a statement that the agency’s own spokesperson qualified in an email as “rather bland”: Behind closed doors, top management was busy negotiating with U.S. interlocutors in the hopes of falling on the right side of the State Department. In a two-paragraph email sent to all staff, the U.N. secretary-general soberly wrote that his team had responded to the latest U.S. declarations “with a call to ensure the delivery of critical development and humanitarian activities.” Other organizations told their staff to refrain from speaking their minds on social media or to members of the press, reflecting a certain amount of fear and uncertainty in the ranks of usually unflappable civil servants and humanitarian workers.

Below the surface, things were rather less calm. A friend shared, during a tram ride, that she had spent her week letting people know her NGO’s job openings were no longer open. Another friend was afraid to lose her work visa if her husband was let go from his U.N. job. A neighbor working for the WHO wondered out loud where the organization would find the now missing billion dollars left by the American withdrawal. Rumors circulated: People were taking their kids out of their very expensive private schools; others anticipated a drastic career change if they lost their jobs.

Organizations that don’t rely on U.S. funds — like Doctors Without Borders, which relies solely on private donations — have found themselves winning this odd game of musical chairs by default. “What would be the opposite of the expression ‘victims of our [own] success’?” joked a senior executive of a Geneva-based organization that works with refugees. For years, his organization had unsuccessfully applied to U.S. grants. Now, this looked like luck.

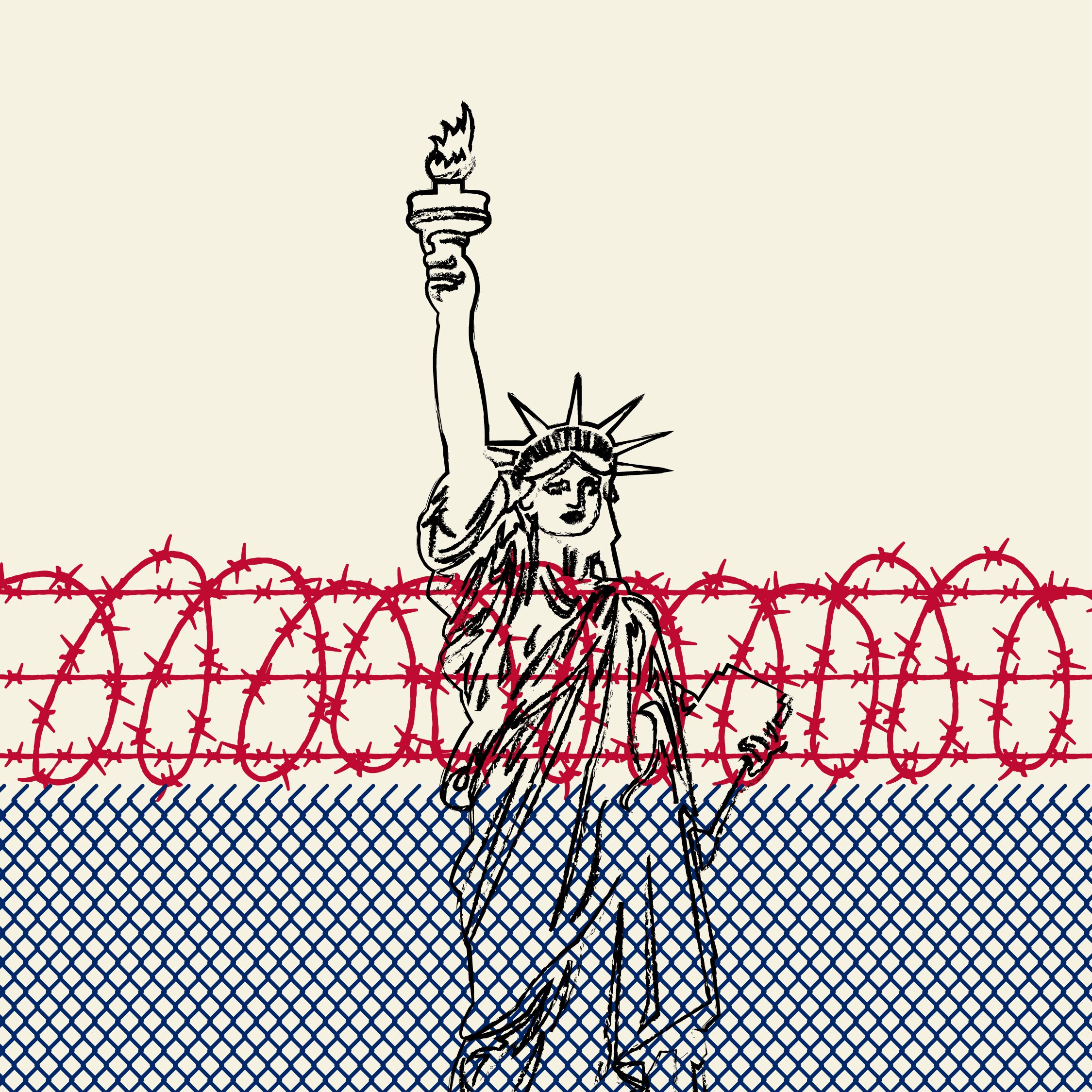

As much as Geneva likes to think of itself as the capital of international development, the U.S. executive orders have only highlighted how outdated the concept of a center of global governance had become.

No one can say for sure when layoffs will come. Bigger organizations tend to move more slowly and have more complex financing schemes, leaving most of their employees in the dark as to how many of them could be affected by the coming cuts. Even smaller NGO structures, quicker to react and more transparent, must hold a two-week consultation with their staff if they would want to lay off more than 30 percent of their employees — a condition guaranteed by Swiss labor law.

Meanwhile, old debates about the U.N.’s raison d’être and staff’s lavish lifestyle have resurfaced. On a private Facebook group for Geneva expats, a communication officer based in the city wrote: “From our chalets along lac Leman beneath the panorama of the Alps, we know we’re extending lifelines to underdeveloped communities but what if we’re contributing to that underdevelopment? What if our literal proximity to global capital isn’t incidental?” A UNICEF officer who had recently published an ad for her rental house in a luxury Alpine ski resort on her own Facebook page, replied: “I would suggest you could look at it from another angle, and that would be that the U.N. world and all the NGOs have forgotten to share their success ... Who’s getting aid to Gaza right now as we type? And Polio [sic] has been nearly eliminated because?”

As much as Geneva likes to think of itself as the capital of international development, the U.S. executive orders have only highlighted how outdated the concept of a center of global governance had become. “We need to [zoom out] from Geneva and the U.S. and shine light on other regions: Latin America, Africa,” said Luis Pizarro, the executive director of the Geneva-based Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, a private-public entity focused on developing new treatments for neglected diseases, such as paediatric HIV and sleeping sickness. “I myself am Chilean. South America does not wait for Geneva organizations to take matters into its own hands.”

A more pressing question: How did the humanitarian sector become so dependent on U.S. money? After World War II, the U.S. helped create the multilateral system in its own image. It actively backed the then-brand-new U.N., contributed to rebuilding Europe through the Marshall plan and created NATO, all of which would last for decades. And in January 1949, in his inaugural speech at the White House, President Harry Truman laid the groundwork for the first global U.S. foreign aid program. By inaugurating the era of development aid, the U.S. was strategically using the concept of universality to undermine what was left of the British, French and Belgian colonial empires while guaranteeing its own access to new markets in developing countries.

Some predict that the vacuum left by the U.S. could be filled by other great powers: “For China and Russia, this could be an opportunity to project their power to the world. There is lots of soft power coming with humanitarian work,” said Bouckaert. “And lots of potentially lucrative contracts too.” China has already increased its participation to the U.N.’s regular budget — it accounted for 20 percent of the budget in 2024, its highest bid so far.

Of course, the Trump administration’s recent decisions have also had another, less desirable, effect on donors: imitation. Argentina announced it was quitting the WHO two weeks after the U.S. did. Israel claimed it would leave the U.N. Council of Human Rights the day after the U.S. said it would. It is unclear whether either can really quit the job, though. Both states are technically “observers” at the Council, meaning that they are present in the room and can take part in debates. As Pascal Sim, the spokesperson for the Council, put it, “a state with the status of observer cannot quit an intergovernmental body it is not a member state of.”

Earlier this week, France’s prime minister passed a law in parliament cutting development aid by up to 40 percent, while Switzerland announced that previously agreed cuts worth several hundred million Swiss francs in the development and cooperation budget for 2025-2028 would affect its contribution to UNAIDS, the U.N. program coordinating the global fight against AIDS. Even though the amounts may seem small compared to the U.S.’s $72 billion freeze, these more quiet moves seem to indicate that, these days, many governments find strength in withdrawal.