Death in Grammar

“Oh, how I admire the capacity of the Spanish language to express uncertainty so precisely!”

NOVEMBER 12, 2024

Among the students taking the preparatory course in phonetics and linguistics during the spring semester of 1997 — a requirement for all students of Spanish at the University of Bergen — there was much talk of the letter. Those who scored a 1.2 or better on the exam would receive an invitation to major in linguistics.

At the time I was obsessed with syntax trees. A syntax tree is an analysis of a sentence in which clause elements, phrases and words are arranged in relation to one another. Unlike dry texts about the Conquistadors in Latin America, crammed with advanced vocabulary, a completed syntax tree gave me a lovely little shot of endorphins. Again and again and again. Although I wasn’t intending to major in linguistics, I was looking forward to receiving the letter, solemnly framing it and hanging it up at my student accommodation.

A couple of months earlier I had returned to snow and general Christmas merriment after three months traveling around Latin America. I had done a four-week Spanish course and picked up an amoeba in my gut. As a parting gift, I had also found myself embroiled in a hostage crisis in Peru. On 17 December 1996, the guerrilla movement Movimiento Revolucionario Tùpac Amaru (yep, that’s where Tupac Shakur got his name) took 500 people hostage at the residence of the Japanese ambassador, and the then President of Peru, Alberto Fujimori, declared a state of emergency. A curfew was instituted, and all foreigners were asked to leave the country as soon as possible. I had little choice but to go home earlier than planned.

Exhausted, I landed at Stokmarknes’ tiny Skagen Airport in Vesterålen. My feet were throbbing — courtesy of a pair of much-too expensive and much-too tight shoes purchased during our stopover in Rome — and my body was weakened after more than a month of diarrhoea and vomiting. And my Spanish? The eight hours a day of private tuition had mostly been devoted to grammar. Dutiful and obedient, I had plugged away at Spanish verb conjugations, but I hadn’t picked up much conversational vocabulary or many colloquial phrases.

I was (and still am) fascinated by the clear right-or-wrongness of Spanish grammar, and yet how that grammar can also express doubt, uncertainty, contradiction and even irony.

The language course, my stay with a host family (they had a 15-year-old maid and a host who yelled louder and louder if I didn’t understand what he was saying), plus the backpacking trips to the Galapagos Islands, the Andes and Lake Titicaca — all of it was financed by my student loan and a stipend. In return, once back in Bergen, I was required to pass Foundational Spanish in reasonably short order.

And while the details of South America’s colonization — the guns, massacres, diseases, dates and heroic feats of masculinity — were dull, I found Latin American poetry and short stories captivating.

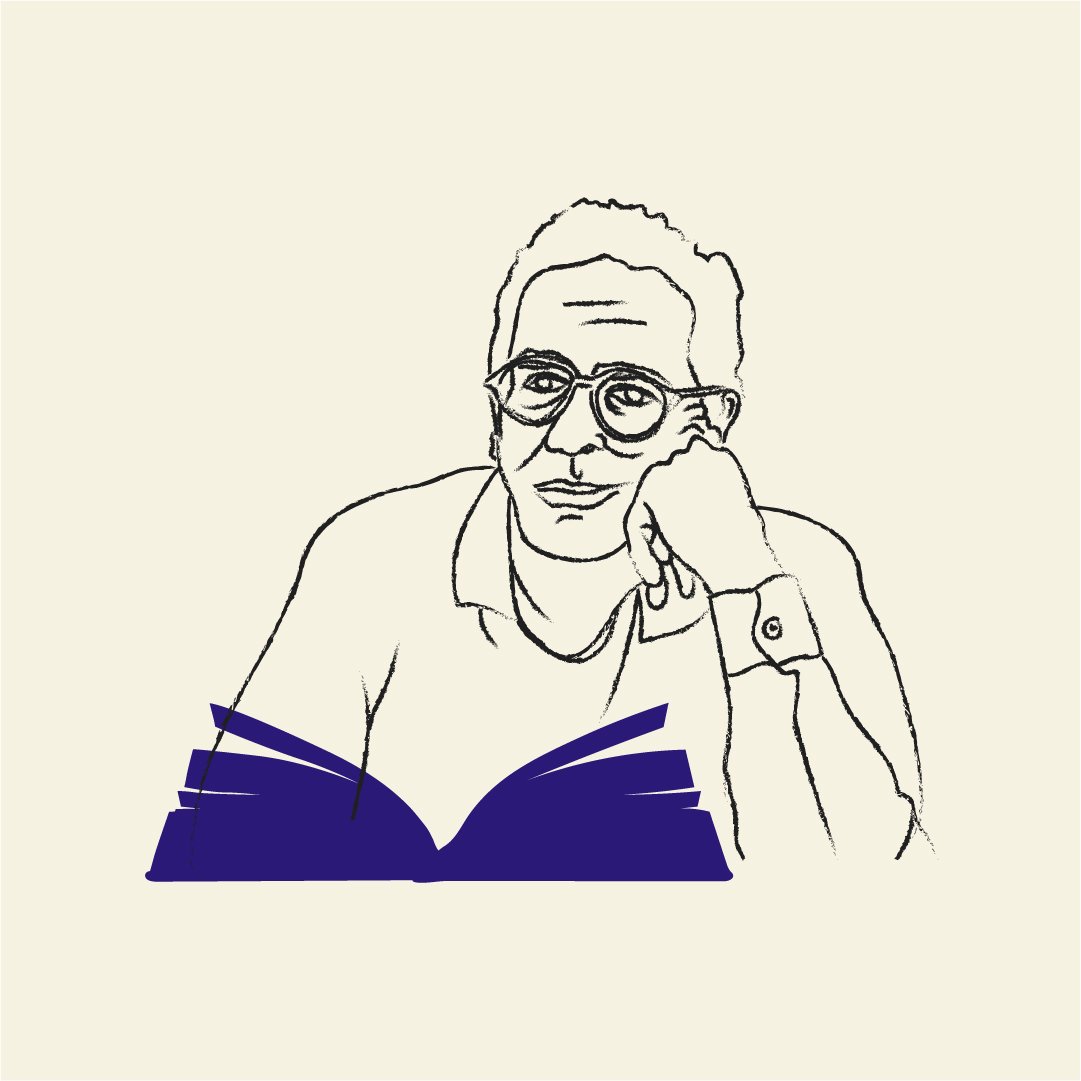

I became fascinated by the Argentinian short-story writer Julio Cortázar (1914–1984), who transformed one character into another — quite naturally — merely by virtue of a grammatical mood that doesn’t exist in Norwegian: the subjunctive. Mood indicates the intention of the speaker. While in Spanish there are three moods — indicative (realis), imperative (commands) and subjunctive (hypothetical) — in Norwegian we use only the indicative and the imperative, with the exception of a few set expressions, such as “fanden partere meg,” which literally translates into English as “may the devil carve me up” and more colloquially as ‘holy shit!’ In this essay I examine solely the semantic use of the subjunctive, and not its more extensive and rule-governed grammatical usage.

We read gloomy, gorgeous and difficult poetry by Alfonsina Storni (1892–1938), also from Argentina. The subjunctive, I discovered, could be used to create a distinctive atmosphere, an uncertainty in the reader: What is happening? Can that be happening? Is the impossible possible? Yes! The impossible is made possible merely by an inflection of grammatical mood.

I battled my way through short stories and poems. The greater the resistance, the harder I worked; at least, after permitting myself my daily dose of syntax trees. And although I may have struggled to fully understand the poems of Alfonsina Storni, I felt them — I understood them emotionally (and grammatically). Her poetry was about a deep yearning for death, and the death she longed for was liberating, relieving, alluring. Death was a victory, death was beautiful.

Alfonsina Storni’s life was full of yearning too. Alfonsina, who was miserably in love with a married man. Alfonsina, who was described as ugly. Alfonsina, who fell pregnant by a colleague and had the child outside of wedlock. Alfonsina, who found a lump in her breast in 1935. Alfonsina, who drowned at Playa del Perla (Pearl Beach) in the resort town of Mar del Plata (Silver Sea) aged 46.

Oh, how I loved it. I loved the heaviness, the beauty. I would sit in the dim reading room at Sydneshaugen with the Blue Spanish–Norwegian Norwegian–Spanish Dictionary at hand, taking notes with my freshly sharpened grey pencil and flipping through Conjugación del verbo — a lovely little grayish-brown thing that included all the Spanish verbs, plus a complete conjugation of all the irregular ones. You simply had to follow the instructions.

I was (and still am) fascinated by the clear right-or-wrongness of Spanish grammar, and yet how that grammar can also express doubt, uncertainty, contradiction and even irony. And as in grammar, so in poetry. A poem is similarly made of constituent parts: It adds up to itself, to a feeling, to a state, to a being. At the same time, poetry reflects the very uncertainty, the enigma, the unbearable all-ness or unbearable nothing-ness of existence.

And this, this can be expressed in Spanish through the conjugation of a single verb. It’s a far cry from Norwegian, where you need to rope in various auxiliary verbs and inevitably end up with a hopelessly knotted sentence. Take, for instance, the verb to die — morir in Spanish, a concrete action. In Spanish, the subject can be packaged up with the verb: In other words, the “I” is unnecessary if I want to say “I’m dying.”

PRESENT

Muero I’m dying

Muera I’m dying?

PAST TENSE

Morí I died

Moría I died

Muriera I died?

Muriese I died?

PRESENT PERFECT

He muerto I have died

Haya muerto I have died?

PAST PERFECT

Hube muerto I had died

Había muerto I had died

Huberia muerto I had died?

Hubiese muerto I had died?

FUTURE

Moriré I will die

Habré muerto I will die

Muriere I will die?

Hubiere muerto I will die?

CONDITIONAL

Moriría I would die

CONDITIONAL PERFECT

Habría muerto I would have died

Oh, how I admire the capacity of the Spanish language to express uncertainty so precisely!

In 2003, five years after taking Foundational Spanish (I had done ridiculously well on the exam, thanks to my knowledge of the subjunctive and feminist Argentine poetry of the 20th century), I made a fresh attempt to learn to speak the language by traveling to Argentina, homeland of Alfonsina Storni and Julio Cortázar, and to the city of Buenos Aires. The goal was to carry out interviews in Spanish, as I had several freelance articles lined up.

A few weeks into my stay, after daily conversations with a teacher whose real desire was to be a full-time actor and communist; after renting a room with a young man who worked for the right-wing candidate in the presidential election and had a serious complex about Norway (he was the descendant of a Norwegian Nazi who had fled to Argentina); after completing a few freelance assignments, including profiling a woman who was obsessively in love with a deceased and rather mediocre pop singer (she visited him weekly at the cemetery, and I distinctly remember her husband loitering in the background, bored-looking, while she passionately kissed the tombstone) — anyway, after a few weeks, or maybe a month, because I’d also finished an article about the country’s spiral into bankruptcy (yep, plus ça change), I found myself standing on a jam-packed bus with my nose buried in someone’s sweaty armpit, while I hung on to the overhead strap as best I could.

I was on my way to a football match at Estadio Monumental, the biggest stadium in Latin America, with a capacity of 85,000 people. I was working on a piece about Iglesia Maradoniana (the Church of Maradona), and a few days earlier I’d interviewed the three founders in the nearby city of Rosario. As far as I could tell, there was minimal use of the subjunctive in our conversation.

In this particular religious community, which today has hundreds of thousands of members, Maradona’s autobiography is the Bible. Their calendar begins with the year of Maradona’s birth, and their Lord’s Prayer starts as follows: “Dear God, who art in football stadiums, hallowed be thy left foot.” The Credo? “I believe in Diego, almighty footballer, creator of magic and passion.” The first of the Ten Commandments? “The ball shall never be sullied.” The firstborn son in each family is christened Diego, and all members take Diego as a middle name. Believers swear on the ball, couples get married at football stadiums — and in this ministry, it was of course the hand of God, not Maradona’s, that scored the notorious goal when Argentina defeated England 1–0 at the World Cup in 1986.

It was there, in the middle of the packed bus, amid that whooping, sweaty crush of men, that I formulated a grammatically correct sentence in the subjunctive — beautiful and perfect! — to my Argentinian companion. I wanted to celebrate, to yank the strap I was clinging to like a horn, but when I remarked on my grammatical genius, triumphant and delighted, he didn’t seem to hear what I was saying.

✺

Back to 1996 and my first encounter with Latin America. After a four-week Spanish course in the Ecuadorian capital of Quito, I went travelling with a student friend in the Amazon. We spent just under a week trekking on foot through the jungle, sleeping under the open skies. This was when the amoeba first came into my life — the stupid bloody amoeba that would eventually cause 10 kilograms of weight loss and countless embarrassing incidents, for example on the world’s largest salt flat, the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia, where we headed some weeks later. By that time the amoeba had made itself well and truly at home in my system, and before I knew it, I was desperately trying to figure out how to maintain my last scrap of dignity. I had little more than a fig leaf plucked off a bush to hide behind, and I could feel the jet building at both ends. Should I tear off my clothes in front of four total strangers? Or should I keep the clothes on and get back into the car in a fetid cloud before driving an unknown number of miles with said strangers?

Don’t ask me which option I chose. I think I’ve blocked it out.

At any rate, that first day in the jungle, before the amoeba had reared its ugly head, we reached a river. The current was strong, and the water much higher than was normal for that time of year. Our guide had launched out into the river but was dragged down by the powerful current, although he managed to cross a bit further downstream. He was strong, pure muscle, he was from the Amazon and he knew what he was doing. The solution for the rest of the group — two tall lads, my tall female friend and myself, average height — was a log across the river. One of the boys went first. Then my friend. She clung on tightly to the log, which the two boys and the guide were holding firmly in place on either side. I saw the current tug at her, but the log prevented her from being dragged along.

Once she had reached the other side, I set out into the water. The bag on my back was filled with containers of water and I gave the straps an extra tighten. Drinking water was important, and it was heavy. My boots felt heavy too, as I stepped into the river. I took a few steps forward, keeping a firm grip on the log, but all of a sudden the water was very high — rising much too high, all the way up to my neck! — and then my legs were knocked from underneath me.

The bag! The heavy bag made it impossible to hoist my torso any higher up out of the water, and the fierce current made it impossible to plant my feet on the riverbed. Everybody on the bank was yelling, yelling not to let go, not under any circumstances to let go.

In my 22 years I’d had experiences that had given me a different perspective on life and death, although I’d never really stopped to think about it much. I was given to proclaiming merrily that I didn’t care if I lived or died. After all, once you’re dead you’re not aware of it, so why would it matter? I’d follow up with a jaunty laugh. Besides, I had a useful ability, one I wasn’t even aware of: I could detach from my body. I simply disconnected from the feeling of having a body from the neck down. Mentally, I abandoned myself.

As I hung from nothing but my fists in the middle of those raging Amazon waters, unable to either loosen the bag or kick off my boots, I don’t remember feeling any fear. Nor did I realize how much river water I was swallowing. I just acted. I moved one hand then the other along the tree trunk, over and over until I reached one of the tall Europeans, who stretched out his long white arms toward me. I remember reeds and bushes and twigs and undergrowth where I came ashore, half hauled, half scrabbling. I don’t remember any reaction afterward either. We simply carried on into the jungle.

Si hubiera muerto …

No, I didn’t want to die that day in the Amazon. Not there, not then.

Alfonsina Storni wanted to die.

In 1938, she drowned herself. I don’t believe her biography, which says she only did it because she’d been told she had incurable breast cancer and was in pain. She had written the most beautiful, most death-desiring poems I have ever read.

Alfonsina has been coming back to me the last three years. I know why. I know why I’ve become preoccupied again by the subjunctive and poetry, why I think back to Foundational Spanish and my days as a syntax tree hugger. It’s because grammar and poetry offer acknowledgement, understanding, resonance — even if I don’t understand them wholly. Poetry brings me comfort, grammar brings me answers, and together poetry and grammar make up a higher beauty, a unified truth.

At the time, Alfonsina Storni’s poetry felt comforting in a way I didn’t understand. Now it is an inexplicable consolation no longer but a clear, raised voice: It’s okay to long for death. Death can be beautiful.

We had two of her poems on the syllabus: the last poem she wrote, “Voy a dormir,” which she sent to the newspaper La Nación the same day she took her own life, and “Epitafio para mi tumba” from the collection Ocre (1925).

Inscription on My Gravestone (Epitafio para mi tumba)

Here I rest, ‘Alfonsina’ written on my gravestone.

Here I rest, and in this well I feel nothing. I am at ease.

Those clouded eyes of mine dart no more glances. Those pale lips of mine give no more sighs.

I sleep a heavy, endless dream. They’re calling to me, but I won’t go back.

I lie in earth, but it doesn’t weigh me down. The winter wind blows, but I am not cold.

My pulse does not quicken with the spring. Summer does not ripen my dreams.

My heart no longer leaps. I am beyond the field of battle now.

What is it saying, walker, that bird? Translate its troubled song for me.

‘The new moon is born and the sea is scented like perfume. Beautiful bodies bathe in foamy waves.

‘A man walks along the shore. In his mouth there is a bee, wild and free.

‘Under the white cloth lies the body that wants another body, one that throbs and dies.

‘The sailors are dreaming in the bow, the girls are singing from the stern.

‘The men set sail. From their clear caves, they journey to unknown lands.

‘The woman asleep in the ground. Jeering at life in her epitaph, delivering one last lie: ‘I am tired of living.’

“Epitafio para mi tumba” is a strange poem. On the one hand, it seems straightforward: a woman reports from beyond the grave how good it is to be dead, but the last strophe is ironic. Life might have been worth living if she hadn’t been a woman — at the same time, it’s as though parts of the poem evade complete understanding. It is hazy, unreal, the way mental illness is experienced as both unreal and real — so it was for me, anyway, when I was hospitalized at Kronstad District Psychiatric Centre from March until June 2022, and for the first time I attempted my own version of it — because I had to, because I was this poem.

When I took Foundational Spanish in 1997, a chord was struck, awakening a sense that there was a darkness in me, darkness that crept out at night, through drunken jokes or in my detailed, violent nightmares.

At the time, Alfonsina Storni’s poetry felt comforting in a way I didn’t understand. Now it is an inexplicable consolation no longer but a clear, raised voice: It’s okay to long for death. Death can be beautiful. Or — so I can’t be accused of glorifying death, I’ll moderate that slightly: the thought of death can make death appear beautiful; death as the last union of life with nature. A final calm, an all-encompassing peace.

Why this spoke to me in 1997 I wasn’t sure, and I didn’t dwell on it. Perhaps I knew unconsciously that thinking more about it would be too dangerous a path.

I Want to Sleep (Voy a dormir)

Teeth of flowers, cap of dew

Herb hands, dear nursemaid mine

Make for me the bed of earth

The quilt of moss

I want to sleep, my nursemaid, take me to bed

Put at its head a lamp

Set it where you like

Anywhere is fine, just turn it down a little

Let me be alone now: Listen, the buds are breaking

A heavenly foot rocks you to sleep

And a bird twitters the pulse

so that you forget … Thank you. Oh, one thing:

if he calls again

tell him not to keep asking, I’ve already left…

Twenty-five years later, Alfonsina came and sat on the edge of my bed. I was lying under a duvet with HEALTH SERVICE printed in blue letters on the stiff white cover.

She moved the bedside lamp so it wasn’t shining into my eyes. Her thick white hair was a frame around an almost childlike face. Alfonsina said she knew what my heart desired, that she understood me, that she knew no one else did. She said she knew I was crying, although I had my back to her and cried without sound or movement. I’m good at that.

She said she knew my pain. She said she loved me, and I felt the warmth streaming from her words. Gently she took my shoulder and turned me to face her. Her hands smelled wonderful. Carefully, she lifted my head into her lap. She brushed back my graying hair, stroked tear after tear from my wrinkled eyes — the same eyes as when I was 16, 17, 18, and had longed so desperately to lie like this in a lap and have my hair stroked while a voice repeated softly, “There, there, my girl. There, there.”

Alfonsina assured me she would let him know if I did decide to leave. But she asked me to stay. “Spring has come,” said Alfonsina as she ran her fingers through my hair. “You may be blind to its colors now, but one day you will discover them anew. One day you will be happy listening to the buds burst open, and watch attentively as spring gives birth to nature, again and again.”

“The good thing about where you are now,” she went on, “is that there are no hooks on the walls or in the ceiling, the mirror in the bathroom is made of plastic and the window is locked. The door to the roof terrace is bolted. You’ve given the responsibility to someone else. I know what it’s like.” She stroked my cheek. “But I’m glad you’re not able do it.”

“I think you are too,” she added. “In a way, you’re grateful that you can’t act on your urge to die in here.”

“Yes,” I murmured in her lap.

“You’ll be alright,” Alfonsina said, tucking me up tightly in the duvet. “You’ll be alright.”

✺

P.S. I got a 2.9 on the exam in phonetics and linguistics. In other words: I never did get a letter.

P.P.S. The translations of “Epitafio para mi tumba” (Ocre, 1925) and “Voy a dormir” (La Nación, 1938) are based on the author’s Norwegian reworkings of the original poems.