Past Plunder

The reparative fictions of Egyptian novelist Sonhallah Ibrahim.

MARCH 28, 2023

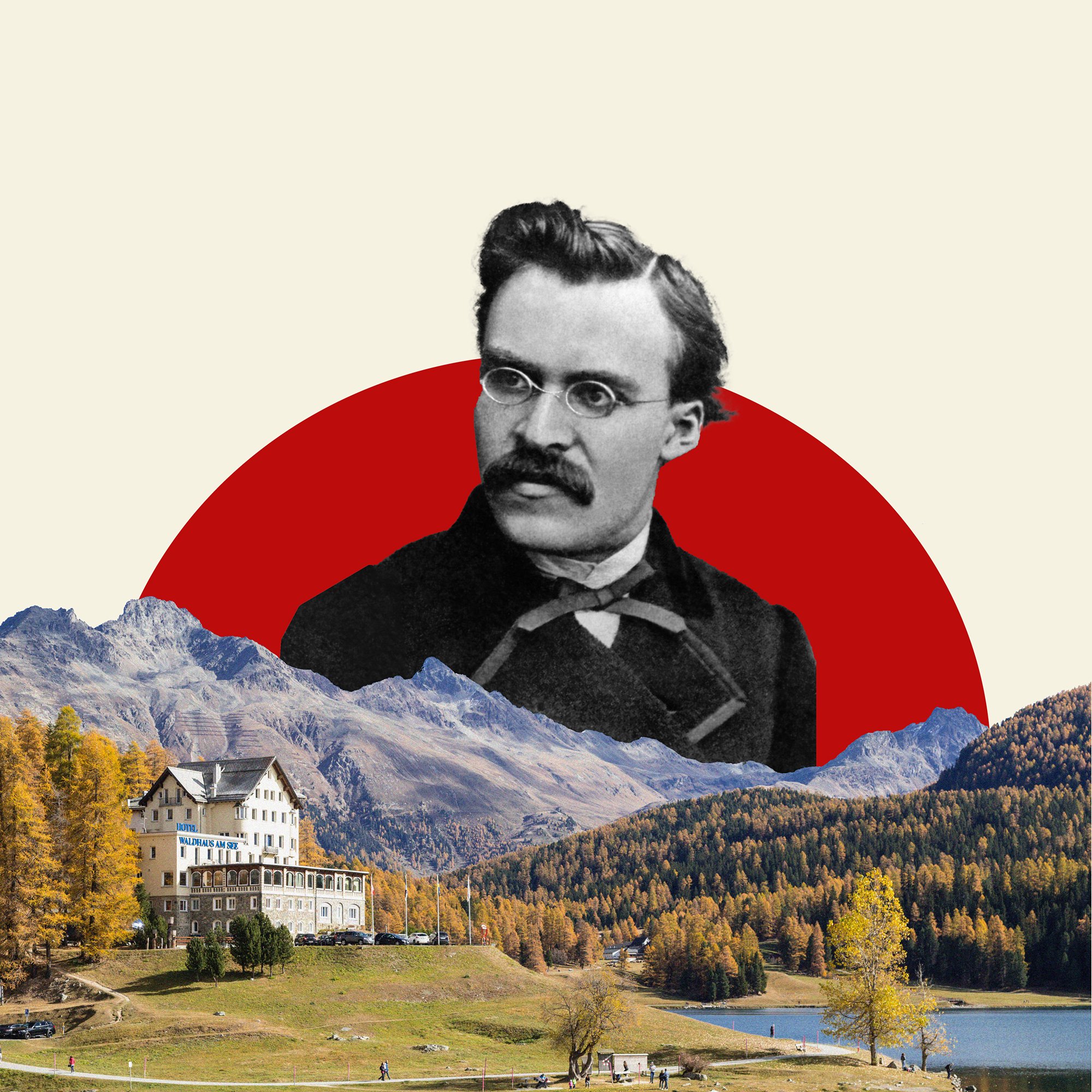

The Battle of the Pyramids 1810/2018, from the book A Tourist Handbook for Egypt Outside of Egypt, Sara Sallam, 2020

REVIEWED:

The Turban and the Hat

By Sonallah Ibrahim

Translated by Bruce Fudge

Seagull Books, September 2022

The first time I heard someone call for reinstating colonial rule in the Arab countries was October 2011. Earlier that year, the unprecedented protests at Tahrir Square later known as the January Revolution had managed to oust Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who had been in power since I was 5. Mubarak was a journeyman with little charisma, and the opposition saw him as more of a kleptocrat than a president. In the last 10 years of his reign, he had been grooming his son Gamal to succeed him as the next president of Egypt. Now the protests forced me to revise my conviction that in this part of the world, political agitation could change nothing.

I took to binge-watching the Al Jazeera debate show “The Opposite Direction,” which brings together two guests with differing views to argue onstage. It was rarely intelligent or insightful, but there was something compelling about getting the pulse of Arab political discourse after two decades of relative political stasis. Over several months I worked my way through the show’s backlog till, one day, I came upon an episode from February 2010 on “colonialism and apology.”

Over the course of the 19th century, France and England colonized much of the Arab world. Few Arab countries gained independence before 1950. I sat watching while two guests debated that fraught legacy.

The first guest was Muhammad Jahid Younesi, an Algerian Islamist politician involved in campaigning demanding that France apologize for colonizing Algeria. The second was the French Libyan law professor Hadi Shallouf. Clad in an off-white tuxedo and burgundy bow tie, Shallouf rather haughtily argued that, compared with national governments, the occupiers had not plundered national resources, oppressed the people or failed to live up to their civic and developmental responsibilities at all. The homegrown regimes were so much worse than the colonial powers that came before them, he said, that it made empirical sense to demand the return of colonial rule.

Outrageous as he sounded, in light of the January Revolution — which marked the failure of the postcolonial state — I felt Shallouf had a point. By then decades of corruption, underdevelopment and abuse had resulted in many liberal-minded Egyptians feeling a kind of misplaced nostalgia for “the European system” of colonial times. Technically, Egypt never became part of a European empire. In 1798, the French led an abortive campaign that exposed Egyptians to the wonders of modern science and weaponry. Nearly a century later, in 1882, the British brought over an army to take control of the economy in Egypt, where they built the railway network and regulated cotton growing. They stayed until 1956. Perhaps political anger over the present had given a nostalgic twinge to the racism and exploitation the French and the British had both perpetrated.

Yet, while movements for reparations were taking hold in other formerly colonized countries, why were serious discussions of how Europeans might make up for the many decades during which they funneled profits out of Egypt — by aiding with the country’s foreign debt, for example — so rare and infrequent? Outside the occasional campaign to retrieve a museum piece taken out of Egypt during the colonial era, why did reparations rarely come up?

✺

In 2011, at the same time that I was watching “The Opposite Direction,” the novelist Sonallah Ibrahim was being hailed as an oracle of the January Revolution. He had always vocally opposed Mubarak. In 2003, he ostentatiously rejected a prestigious state prize, the Arab Novel Award, given by Mubarak’s Ministry of Culture. When the moment came, Ibrahim went up to the podium at the Cairo Opera House and announced that he had no choice but to emphatically decline “the honor of a government that does not have the credibility to bestow it.”

Ibrahim’s 1964 novella That Smell had been a formative influence on me. He was less interested in the West making up for past wrongs than in an Arab renaissance to counteract Western hegemony. He believed in socialism and Arab nationalism. “The reason for all the problems we suffer in the Arab world,” says Professor Shoukri, the left-wing historian hero who populates two of his books, “is that we did not manage to establish an advanced national industry. At the beginning the Ottomans divested us of our resources … and after them came the French and the English.” This would be a fairly accurate statement of Ibrahim’s own view.

Nasser had turned the country from an ailing kingdom under British occupation to an independent republic leading the struggle against colonialism in Africa and the Middle East. But by the time he died the country was in dire straits. It was inevitable that, from then on, the state would adopt a capitalist, pro-American ideology that, to Ibrahim and many others, felt like a betrayal.

Ibrahim had lived through many stages of Egypt’s political hopes and disappointments. When Ibrahim was barely 20, he was caught up in the revolutionary leader Gamal Abdel Nasser’s 1959 purge of communists and forced to spend five years in prison. On his release in 1964, he was penniless and terrified, without a university degree. While trying to write a never-to-be-completed collection of short stories that he hoped would be his first book, he began keeping a daily journal to reorient himself.

That diary eventually morphed into That Smell, which made Ibrahim’s name in the literary world. Using a limited vocabulary and terse sentences, That Smell is devoid of abstraction or metaphor, evoking the claustrophobia and emotional emptiness of Egypt in the mid-1960s. With a deadpan brutality, it narrates the systematic abuse of a young prisoner that the hero witnesses before his release, and the hero’s subsequent inability to make love and his self-consciousness when later he visits a well-off family. Notably, while Ibrahim makes no attempt to mimic Egyptian spoken dialect, which is distinct from written Arabic, the novel still manages to sound vernacular. The book introduced into Arabic fiction the idea of a narrator-protagonist who is neither hero nor anti-hero but simply witness, evoking an existential tradition perhaps most clearly exemplified by Camus’ The Stranger.

That Smell exposed a world irrevocably in decline. Egypt’s humiliating defeat in the 1967 war with Israel was followed by Nasser’s death in 1970. Nasser had turned the country from an ailing kingdom under British occupation to an independent republic leading the struggle against colonialism in Africa and the Middle East. But by the time he died the country was in dire straits. It was inevitable that, from then on, the state would adopt a capitalist, pro-American ideology that, to Ibrahim and many others, felt like a betrayal.

[Jabarti’s account] is a powerful evocation of the complexity of the Egyptian response to what is widely seen as the first major encroachment of modernity: fascination with previously unknown wonders, and resentment of the violence, lies and abuses in which they are wrapped.

With The Turban and the Hat (published in Egypt in 2008, and now translated into English by Bruce Fudge), Ibrahim made his definitive, if elliptical, statement on Egypt’s colonial encounter. Presented as the text of a previously undiscovered manuscript, the book takes the form of a diary written by a student of the great Cairo historian Abdul al-Rahman al-Jabarti, who famously chronicled Napoleon Bonaparte’s three-year occupation of Egypt from 1798 to 1801. Jabarti’s account of the French is damning, but it makes occasional room for the awe he obviously felt for their scientific prowess. It is a powerful evocation of the complexity of the Egyptian response to what is widely seen as the first major encroachment of modernity: fascination with previously unknown wonders, and resentment of the violence, lies and abuses in which they are wrapped.

The diary follows the rise of Muhammad Ali Pasha, who established his own dynasty in Egypt in the first half of the 19th century and is considered the founder of the modern state. Pasha transformed what had become an Ottoman backwater into a vibrant regional hub. He also sent prospective professionals and bureaucrats to study in Europe, presiding over what would become known as a renaissance that accompanied the emergence of modern Egypt in the wake of Bonaparte’s departure.

The Turban and the Hat opens in medias res. The narrator-protagonist — nameless like That Smell’s — follows a crowd back to the house of his teacher Jabarti to report Bonaparte’s victory over Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey, Egypt’s joint rulers, at the decisive Battle of Imbaba. “So, in defeat our two rival emirs finally come together,” Jabarti comments ironically.

Ibrahim uses the deadpan observations of an unremarkable witness to capture a world in flux. A young Mamluk, a member of the ruling warrior class to which the beys belong, rides through the streets and taunts pedestrians with his sword. A band of Ottoman Janissaries commandeer an old man’s mule. “Emaciated peasant women in black galabiyas” — the traditional tunics still worn in Egypt — “thin men, their blue shirts cinched round their waists with rough cords of hemp.”

Ibrahim is too aware of his modern audience and too eager to explain his setting for this to be a plausible diary from that time. So much research is seamlessly integrated that the book sometimes reads like a time traveler’s travel guide. But, aside from improving on Jabarti’s account for contemporary readers, the descriptive energy is so engaging that it is easy to maintain suspension of disbelief.

The translation by Bruce Fudge is vivid and precise, so that the English version of Ibrahim’s text brings late medieval Cairo to life just as well as the original does. What it does not convey is the subtle way Ibrahim plays with the archaic constructions and cadences of the historian Jabarti, whose work Ibrahim references. Jabarti wrote in a uniquely colloquial idiom, mixing standard grammar with vernacular diction in a sprawling, conversational style. Ibrahim brings his own trademark concision and clarity to that early modern Arabic, evoking Jabarti’s linguistic landscape in a far more accessible way.

The storyline that unfolds is that of the French occupation itself. While working at the Institut d’Égypte — the gathering point of the 167 “savants” who discovered the Rosetta stone and produced the monumental encyclopedia of scholarship the Description de l’Egypte — Ibrahim’s young witness begins to keep his own journal. Some 250 pages later, the British warships that will push the French out of Egypt have dropped anchor, the Mamluks are still in hiding and the grand vizier has arrived from Istanbul to take charge.

In the meantime, the narrator has accompanied the French on their campaign to Syria, where he witnessed the ravages of the plague and unutterable cruelties. He has had an affair with one of Bonaparte’s mistresses, Pauline Fourès. She hurts his feelings. His friend Suleiman al-Halabi, the 23-year-old Kurdish student who assassinated Bonaparte’s successor in Egypt, was tortured in punishment: his hand was burned and he was impaled through the anus. In one of many episodes that recall the hero of That Smell, the narrator has even been jailed after putting up posters inciting French soldiers to desert and return to their country.

Ibrahim’s genius comes through in the way these encounters alter the witness just as the presence of the French alters the identity of Egypt. He begins to count time in new ways:

I noted the date according to the Islamic calendar, but then I substituted the Christian date, as I had learned to do from a French merchant. I multiplied the Islamic year by 131, divided the result by 135 and then added 621 to get the corresponding Christian year.

In Jabarti’s library, the narrator notices “an incomparable copy of al-Jawhari’s Arabic dictionary that stood out because it was not in manuscript form but had been printed as a lithograph in Turkey” — indeed, the French brought the printing press to Egypt. He grows familiar with the site of the modern restaurant, where men and women mix:

Through the open door I could see the Frenchmen seated on chairs around what looked like raised wooden benches. An attendant was serving them plates of food. I asked one of the donkey drivers whose house it was, and he told me it was a place for eating.

The fraught relationship between colonized and colonizer is powerfully exposed during a conversation between the narrator and one of his friends. The friend, a kind of prototype of the modern Islamist, prefers the oppression of the Mamluks — the old order — to that of Christian infidels. For him, the infidels must be fought no matter what. The hero, perhaps a prototype of the Nasserist, is less certain. He can see the modernity the French have brought along with them — the possibility of a progressive future — and the potential of that change to free Egyptians of Turkic tyranny.

The French go up and down the lanes and alleys to harass the women, said Abd al-Zaher.

—But we’re ready for them, he added with determination.

I recited a verse from the Quran: and We never destroyed the cities, except those whose inhabitants were evildoers.

—You forget the first part of the verse, he said. Yet thy Lord never destroyed the cities without having sent in their midst a Messenger, to recite Our signs unto them.

—But no one has come yet. Anyway, overall we’re better off than we were under the Turks and the Mamluks.

—Are you mad? They were Muslims, not Christians.

—I heard from my teacher that the French aren’t really Christians. They’re materialists.

—O Master, he asked mockingly, and who are these materialists?

—They deny the resurrection and the Hereafter and the Prophets, and they claim the world is eternal and that all cosmic events are caused by circular movements. They believe that reason is the best judge and that Muhammad, Jesus and Moses were all wise men and that the laws they brought were their own creations, only intended for the times they were living in.

—So they are unbelievers, and we must fight them.

—And how are we going to do that?

This is not a tension that Ibrahim wants to resolve.

✺

Bonaparte — his presence, his plunders — has continued to be a topic of discussion and argument in Egypt for more than 200 years. In 2008, the same year that The Turban and the Hat was published, the Parisian Institut du Monde Arabe commemorated the French occupation of Egypt with a 3.6 million euro exhibition titled “Bonaparte et l’Égypte: feu et lumières.” (People forget: Bonaparte was not yet “Napoleon I” when he was in Egypt).

Critics took aim at his implication that Bonaparte was responsible for turning Egypt into a modern nation-state. It was, as one headline put it, as if the country were celebrating its occupation.

It featured “national treasures” supplied by the Egyptian government. Mubarak’s longtime minister of culture Farouk Hosni opened the exhibition, joining the Institut president onstage to make a statement in which he claimed that France’s expedition had paved the way to the renaissance Egypt saw at the start of the 19th century. Hosni’s remarks led to an outcry in the Egyptian press. Critics took aim at his implication that Bonaparte was responsible for turning Egypt into a modern nation-state. It was, as one headline put it, as if the country were celebrating its occupation. Others felt that Hosni had attempted a kind of cosmopolitan sensibility that could be anti-colonial without discrediting meaningful connections to Europe. But, from the standpoint of Egyptians, can such an approach exist?

In The French Law, his 2008 sequel to The Turban and the Hat – released later in the same year – Ibrahim seems to suggest not. The novel sees Professor Shoukri, Ibrahim’s historian hero, travel to France to participate in a conference on the French campaign with a newly discovered manuscript: the text of The Turban and the Hat. While there, he meets a woman, Celine, who does community work with immigrant children. They seem to hit it off until his last night in Paris. She gets drunk, confides that she has cancer and rages against his postcolonial ideas, saying that former colonial subjects should be grateful for their colonizers and confessing that she actually hates the immigrant children with whom she works.

The next morning Shoukri wakes up early for his flight home and finds the conference program on which he had written his contact information for Celine the night before. “My response,” she has added in pencil, as though answering an invitation to be in touch, “is precisely that you are a naïve, backward human being.” It is clear that, although she may have felt some attraction to or intimacy with the professor, the Frenchwoman does not regard an Arab as worthy of her affections.

While this exchange doesn’t do justice to the complexity and nuance so carefully developed in The Turban and the Hat, it does illustrate that, for Ibrahim, however much our former colonizers pretend to be fair, they will never see us as equals. Perhaps only a sense of national identity capable of accumulating power — not one that needs to beseech past conquerors for an amende honorable — can provide hope for the future.

But, while we wait for such a sense of identity to manifest — and wait we must — what do we make of the past? If not in power then in knowledge, and if not in knowledge then in the capacity for historical evolution and creative feeling, perhaps the only reparation we should insist on is seeing ourselves as peers.