Translating from Latvia’s Threatened Languages

DECEMBER 17, 2024

The Reporter’s Notebook is our monthly interview series with Dial contributors. To receive these conversations directly in your inbox, sign up for our newsletter.

✺

A conversation with writer and translator Will Mawhood, whose translation of poetry from Livonian, a threatened language in Latvia, appears in our Deadlines issue, alongside an introduction on the literary traditions of Livonian and Latgalian.

Will Mawhood, a writer and translator based in Riga, came to Latvia almost entirely by accident. For the past decade and a half, he has written about the wider Baltic region. His interest in language led him to Livonian and Latgalian, two regional languages that are still spoken in pockets of Latvia, despite past efforts to eradicate them.

Latgalian, often claimed to be merely a dialect of Latvian, was discouraged and stamped out from the media and public sphere under nationalist rule in the 1930s. Livonian, which shares no common origins with Latvian, was the daily language among a string of tiny fishing villages on a peninsula in western Latvia before the country was forcibly absorbed into the Soviet Union. Today, the language is seeing an improbable revival. There are now a few dozen fluent speakers, and “since three of them publish poetry in Livonian, its promoters light-heartedly claim that the language has the highest proportion of poets of any in the world,” Will writes in his introduction.

THE DIAL: How did you first come across these two languages? What about them intrigued you?

WILL MAWHOOD: I came to them through my interest in Latvian, which I developed just through living in Riga. Oddly I was initially fascinated not by the sound of Latvian but by the way it looks. The diacritics struck me as quite unusual for a European language.

I became aware of Latgalian through visiting the region, Latgale, which is the eastern-most part of Latvia. It has quite a different history from the rest of the country, which has left traces in the culture, religion and language. There is an ongoing debate about whether Latgalian is a dialect of Latvian or whether it is an entirely separate language. The idea that you cannot be sure if something is a separate language or not was very confusing to me at first.

Because the Latvian literary world is so small, I ended up translating the text for the first English-language students’ book for learning Latgalian a few years ago. That was an interesting challenge — I already had some knowledge of Latgalian but I had to work on it a lot. You can partially read it if you understand Latvian, but there are these words that are unexpected or have different meanings or you’ve just never seen before.

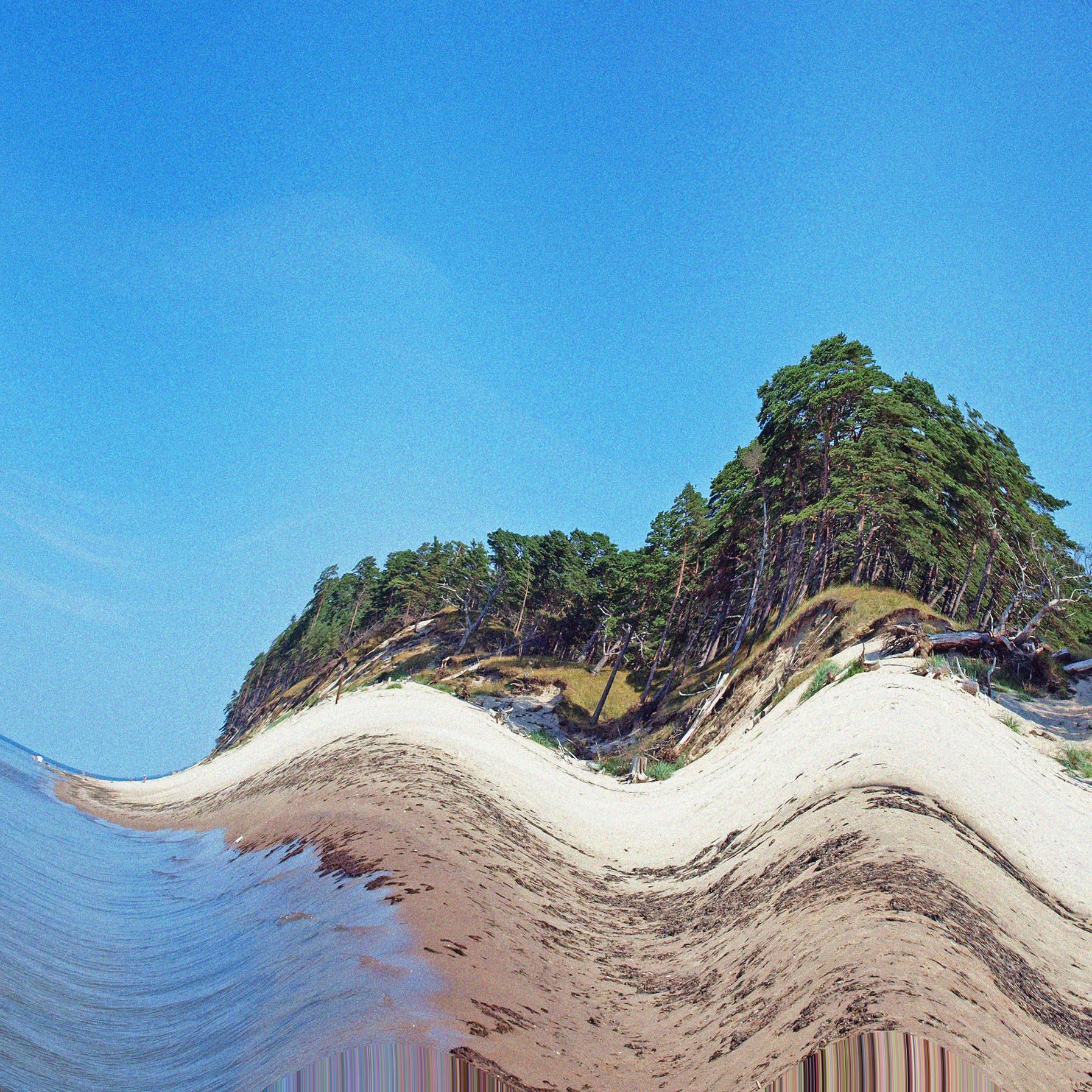

With Livonian, partly I became interested because I absolutely love that part of Latvia. The Livonian coast is the northwestern tip of Latvia, it’s a peninsula that becomes increasingly sparsely populated as you go north. I got to realize that one of the reasons that area is so unspoiled and kind of perfect is because it was heavily militarized by the army and the border guard under the Soviet Union. Because most of those villages were fishing villages, people were not able to continue with their work and their way of life. I was interested that such a small community had managed in such a determined way to keep hold of their language.

THE DIAL: How did you go about becoming acquainted with their literary traditions and the contemporary work being produced in them?

WM: With Livonian, it was relatively easy because the tradition is so small — which I don’t mean in a dismissive way at all, it’s very impressive for a community of that size. But the literary tradition is not much more than 100 years old and for the past 50 years the number of people writing in the language has been no more than a handful. So it’s not very difficult to familiarize yourself with what’s been written.

With Latgalian, I’m still discovering what’s out there. I did some additional research for this piece and that was really interesting and fun. It’s a literary tradition that is also reviving but it’s always had many more speakers than Livonian and it goes back further, to the 18th century. So it was harder to get a grip on in a short time, but I’ve been interested in it for years so it was just a case of putting it all together.

THE DIAL: Is there interest in these languages in Latvia?

WM: Everyone in the country will have heard of both of these languages, especially Latgalian, because it is spoken by at least 100,000 people on a day-to-day basis. If you’ve never heard Latgalian before and you’ve only heard Latvian, you would find it quite difficult to understand. There are quite a lot of different words, including common words like “to read” and “he” and “she.” But most Latvians have had some exposure to it — people often have ancestry in that part of the country, as there’s been a lot of emigration from Latgale.

Some people are a bit sensitive about it being described as a distinct language (in legal terms, it’s defined as a variant of Latvian). Latvian itself has often struggled to survive as the primary language in Latvia, especially during the Soviet occupation when Russian came to predominate in many fields, so it’s a very deep fear in Latvian culture that the language will basically disappear and die. So some people dislike that you’re in some ways splitting the language further.

THE DIAL: What do you make of there being so many poets working in Livonian, relative to fluent speakers?

WM: Well, there aren’t really so many, there are three. But three out of around 30 is a large proportion!

I suspect it probably has something to do with the circumstances of how the community came to leave its homeland after the Soviet army came in and started heavily monitoring the area. Because it happened so suddenly and in such a traumatic way — Livonians had to abandon their homes and their traditional way of life — Livonians were probably very motivated to keep their community alive, even though doing so was very difficult because of how scattered they were. There were also limitations imposed by the Soviet Union. You were not allowed to declare you were Livonian, for example, on your passport, where there was a section for ethnicity — you had to be Latvian or something else. As soon as it became possible to promote Livonian, after Latvia restored its independence, there was immediately an upswing.

THE DIAL: You translated the poem published in this issue from Livonian. How did you familiarize yourself with the language and its very specific cultural context?

WM: It’s definitely the strangest translation I’ve ever done.

For this translation, I was working largely from the Latvian version. Almost everything published in Livonian is also published in Latvian — certainly since the restoration of independence. But Valts Ernštreits, who I’ve known for a long time — he writes poetry in Livonian and is probably the most prominent expert in the language — sent me a word for word translation of the Livonian text, because I wanted to get it as close as possible to the original phrasing.

I had a sense from reading Livonian poetry previously, and having read about Livonian culture and history, that the particular geographical theme of the poem does recur again and again. Sometimes in a very idyllic way — it is a really gorgeous part of the world — and sometimes in quite a dark way, often reflecting the fact that the peninsula became almost inaccessible for a lot of people.

It’s an example of a poem that’s gained a certain poignancy through the later context. When Kõrli Stalte wrote it, in the 1930s, I believe it was written as a kind of celebration. I imagine things seemed reasonably optimistic for Livonians at the time — after the Republic of Latvia was declared, they were able to set up their own organizations, schools, newspapers and so on, although there were still some frustrations. But within a decade or two, the area went on to become heavily militarized and people would have to flee. So the poem gains a different quality.

THE DIAL: Do you have a favorite word or expression in either language? Did they change your perception of Latvian people and history in some way?

WM: Latgalians are generally perceived in Latvia to be quite hospitable and kind of hearty people, so I like that the most common word for “hello” in Latgalian (vasals) can also mean “cheers!” (as well as “bless you”).

THE DIAL: What interests you in Latvia, and the Baltic region, more generally? How did you come to live here after growing up in the U.K.?

WM: I’ve been living in the Baltics on and off since 2011. I came here entirely by accident. I wanted to teach English as a foreign language and was offered a job in Tallinn, in Estonia, after which I moved down here to Riga. I think what I found fascinating was just how completely different it was from my expectations — in terms of language, architecture and culture.

I started the publication Deep Baltic in 2015 because I was quite frustrated by the lack of depth in coverage about the Baltic states. It’s quite difficult to sell stories to English-speaking media about this part of the world. Part of which is understandable, they have lots of things to cover and these are very small countries. So I set it up as an outlet for things I’d written but then people who were in a similar position to me were interested in submitting pieces. It’s an outlet for people to put things that the “mainstream media” would not be so interested in.

THE DIAL: Do you have any future translation or reporting projects in the works that you’re particularly excited about?

WM: I’m working on a story about a village in Lithuania that declared itself independent after World War I and existed in a semi-independent state for five years. I’m also doing translations for a Latvian author called Vilis Kasims, who is very interesting and a very unusual writer. He does what he calls “miniatūras” (miniatures) that are often quite dream-like and just a page or two. But he’s started writing longer fiction, too, as well as non-fiction. He has quite an interesting backstory where his mother was from a part of Moldova called Gagauzia, which was originally a Turkic-speaking enclave. Having grown up in the Latvian countryside, he has an interesting view of coming from two quite different cultures. I’ve been working on those translations, and hopefully we can get something published in English.

WILL MAWHOOD is a Riga-based writer who translates from Latvian and Latgalian. He is the editor of the website Deep Baltic.

TESSA AUGSBERGER is a German-American writer from Los Angeles, California. She attends Dartmouth College, where she is a Hanlon Scholar and serves as president of Dartmouth’s undergraduate history honor society. She enjoys writing satirically about style and culture and writes a twice-weekly newsletter called Faux Pas on Substack.