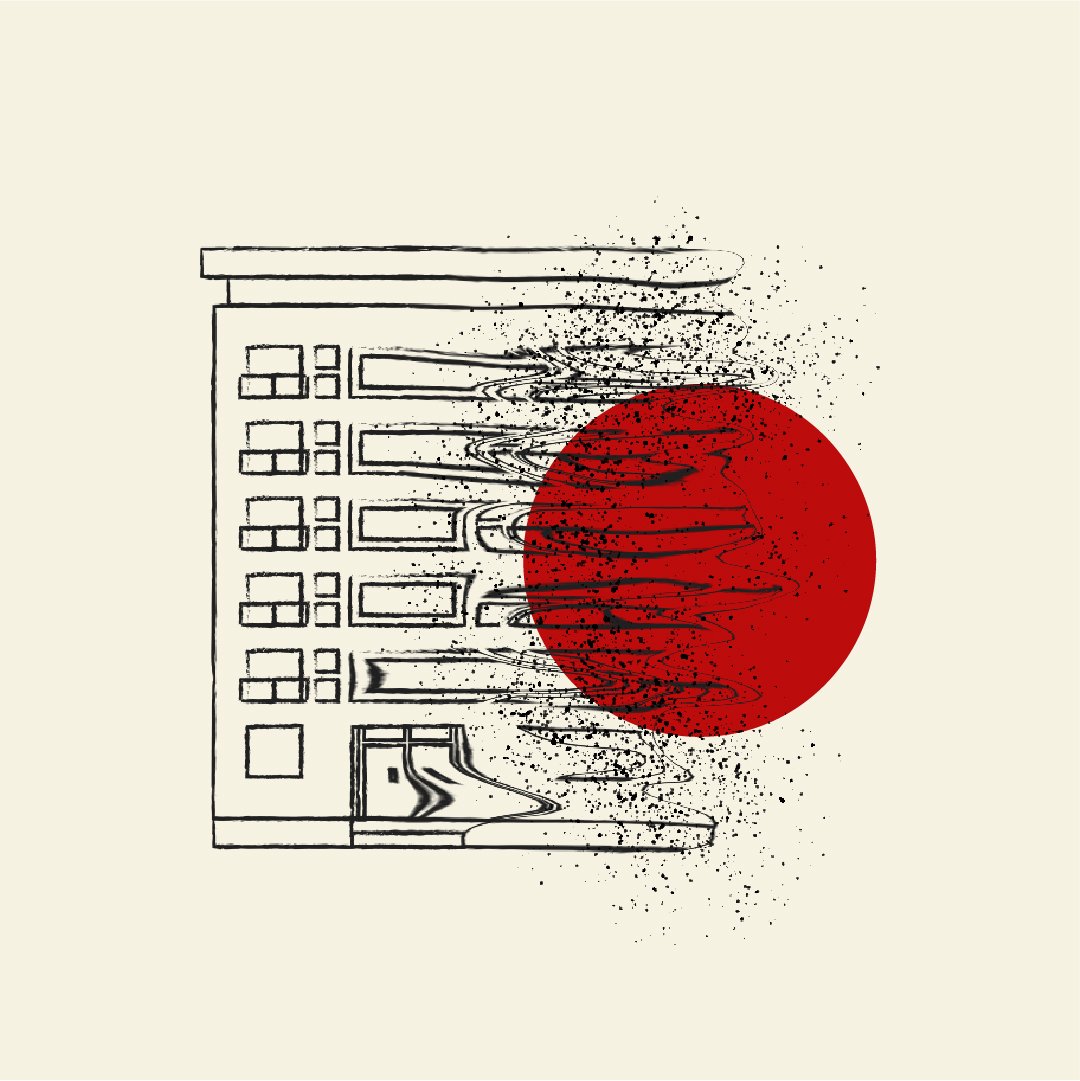

Total Demolition

Behind the evictions transforming Mexico City.

DECEMBER 17, 2024

Just before midnight on February 23, 2024, the residents of Puebla 261 heard a pounding at the entrance of their apartment building. It sounded like someone was ramming the doors with a trunk. The sprawling art-deco building, with 21 apartments, sits in the heart of the Roma Norte neighborhood down the street from a café-bakery frequented by tourists. Its inhabitants count among some of the last old-timers on the block in the center of the capital’s tourist district.

When Pedro, who moved into the building 53 years ago, heard the intruders’ blows, he peeked out the window. Ten vans, belonging to the capital’s investigative police and the National Guard, lined the street.

The sound of blows resounded through the building, and the rest happened in a rush: Dozens of police swarmed the rooftop apartments where the residents took refuge. They knocked down doors and beat the neighbors indiscriminately. They shot Pedro in the eye with a rubber bullet gun; they hit his sister María over the head, drawing blood. Another neighbor, also bloodied from a beating, fainted.

“We wanted to make phone calls, we wanted to record, but the police officers stopped us from using our phones. They threatened us, they intimidated us, they told us to sit down like dirty criminals, and they said that if we used our cell phones they would take them away,” María recalled. (All neighbors’ names have been changed to prevent further retaliation.)

When Magdalena, a tattooed single mother with a young daughter, saw the police attempting to break into her apartment, she offered to open the door herself to assuage her pets. The police shut themselves inside, along with a group of men in plainclothes, carrying a ziploc bag filled with baggies of a green substance. When Magdalena realized what was happening, she cried out: “They’re planting drugs on me!”

With the neighbors rounded up on the roof, the police approached a man who had come to visit earlier that evening. They asked if he lived in the building; he said no. “Yes, you do,” they responded, then arrested him for selling drugs.

The 20-minute operation left the residents of Puebla 261 on the street, without a home or possessions. No one explained what was happening; no one read them their rights or explained the reasons for the raid.

Police rounded the neighbors up and forced them out of the building. One man, left bloodied and unconscious, had to be carried out. Downstairs an ambulance awaited them. When he and Pedro approached the ambulance, the police handcuffed them. In total, police arrested three people on charges of drug-dealing, crimes against health and resisting arrest.

The neighbors waited for an hour on the sidewalk with the police inside the building. Then the police posted an official seal on the door of Puebla 261, the residents’ belongings still inside. The sticker was a marker that the prosecutor’s office had seized the building as evidence in a drug dealing investigation.

The 20-minute operation left the residents of Puebla 261 on the street, without a home or possessions. No one explained what was happening; no one read them their rights or explained the reasons for the raid. “They just told us that at the public prosecutor they would let us give a statement, which never happened,” said María. “They just told us, when we were out of the building, that the building was being seized for drug dealing and drug-related crimes.”

The face of central Mexico City has changed over the last decade. Digital nomads, Airbnbs and trendy restaurants have proliferated. Migrants from the United States and Europe, who bring dollars and euros, have become an increasingly common sight in the city center. The businesses that line the streets of desirable districts appeal to the tastes and budgets of the global north: Trendy cafes replace family-owned torta shops. Puebla Street itself, with its frequent tourist traffic, is a microcosm of the changing city center.

Mexico City’s transformation is not the inevitable result of gringo migration, though: It relies on institutions like the prosecutor’s office, the National Guard and the police, which use state violence and, in this case, drug trafficking accusations to dispossess residents.

✺

About 3,000 court-ordered evictions took place each year in Mexico City between 2014 and 2018. After a slight drop during the Covid pandemic, the city recorded 4,000 evictions in 2022. In typical civil eviction proceedings, people are evicted after trials for not paying rent. In the cases that we have reported, we found that residents were never notified, depriving them of the right to defend themselves in court, and the person claiming the unpaid rents had no relation to the building.

These seizures do not go before a judge. No external control exists outside the prosecutor’s office. The residents, often after years of attempting to obtain documents for their homes, instead receive criminal charges.

Some 30 percent of 100 evictions we have followed since 2016 were carried out by a new division of Mexico City’s prosecutor’s office, the special environmental prosecutor.

This office created a fast track to empty out buildings caught in decades-old disputes. Homes in Mexico City are commonly passed down from generation to generation without finalizing legal titles. Thirty percent of residents in the city center lack papers for their dwellings, according to data from the Autoridad del Centro Histórico, a public entity in downtown Mexico City. Often, an owner dies without transferring their rights, leaving buildings in a legal limbo.

Mexican law recognizes residents’ right to possession. Longtime inhabitants have the right to stay and receive the legal titles to their homes. But the process of acquiring those papers from the city’s housing authorities involves decades of bureaucratic twists and turns.

When the prosecutor’s office seizes a building, it overrides the residents’ right to possession, expelling them with all their belongings inside. The prosecutor purports to seize buildings that are involved in litigation proceedings, but in practice, it carries out evictions on homes that are in legal limbo. It does so by inventing false charges against the residents, usually accusing them of illegally invading and occupying the building. The prosecutor then uses that fabricated crime as justification to seize the property and throw the residents onto the street. These seizures do not go before a judge. No external control exists outside the prosecutor’s office. The residents, often after years of attempting to obtain documents for their homes, instead receive criminal charges. Even after the residents leave the building, the charges often remain active.

The prosecutor’s office publicly maintains that its modus operandi is a legitimate way of maintaining custody of properties in dispute. In a recent publication on TikTok, the current head of the prosecutor’s office, Ulises Lara, outlined the division’s obligations: “This specialized prosecutor’s office oversees everything related to urban issues, like squatted apartments, construction of higher floors without permits and construction problems related to the wrongful sale of buildings.” (A caption added that the office guarantees the respect for our environment and the security of urban property.”) The office has left hundreds of families homeless, deepening the housing crisis for lower-income families with deep roots in the city. Meanwhile, the office turns the properties over to third parties who have no history of a relationship with the building — banks and real estate companies that claim legal rights to properties in the city’s most desirable neighborhoods, seeking to redevelop the land. In several cases, the buildings have been torn down for new, denser apartment complexes to be built. In the case of Puebla 261, which we originally covered as part of a documentary series, the prosecutor’s office went one step further and used drug trafficking charges to empty the building. Neither the prosecutor’s office, nor the special environmental prosecutor, responded to The Dial’s requests for comment.

Even though the institution had not finished the process of purchasing the still-occupied building (it had not yet formally registered the property), the bank filed a suit against the tenants for unpaid rent.

The troubles in Puebla 261 began in 2017 with an illegal sale. The former owner notified the residents that he planned to sell the building. The neighbors began organizing to purchase their home themselves, but before they put down an offer, the owner notified them that a bank, Banca Mifel, had already bought the property. The sale violated the right of first refusal that Mexico City law enshrines for renters: Owners must first consider offers by a building’s current tenants before seeking other buyers.

In December 2018, one of the residents received a notice that they owed rent to Banca Mifel. Even though the institution had not finished the process of purchasing the still-occupied building (it had not yet formally registered the property), the bank filed a suit against the tenants for unpaid rent.

Since then, the residents have faced constant harassment. Police and civilians broke into the building and began to destroy the building with the residents still inside. Banca Mifel attempted to install private armed security guards inside the building. A bank had also acquired the plot next door to Puebla 261, now an abandoned lot, and residents believed that the bank wanted to acquire the land to build a massive new development, like the shopping malls and apartment towers that increasingly dot the landscape around them.

The residents continued to push back. Along with others from across the city facing arbitrary evictions, they formed the Red de Desalojadas de la Ciudad de México (Mexico City Evicted People’s Network). The grassroots organization joined the historic working-class housing organization in Mexico City, the Movimiento Urbano Popular (Urban Popular Movement).

The group started to publicly address the housing crisis caused by forced evictions, organizing demonstrations and demanding a response from the capital’s authorities. When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Mexico, the network organized to call for a moratorium on arbitrary evictions, adopting the slogan “to stay at home, you have to have a home.” But the authorities’ operations continued. By the time of the false anti-drug operation, fewer than 10 families remained in Puebla 261, down from 35 a few years before.

The prosecutor’s investigation file alleges that Puebla 261 was abandoned and being used, presumably by intruders, for drug dealing: An anonymous complaint for drug dealing in the property was made on February 20, just three days before the eviction.

After the seizure, the prosecutor’s office turned over the building to a new trust at Banco BX+, unrelated to Banca Mifel. The procedure left the residents without answers once again. The only proof of the new ownership was the prosecutor, who told the neighbors that the bank had papers to prove its legal possession of the property. In 2021, Banca Mifel distanced itself from the case, telling the newspaper La Jornada that it was “not the owner of the building,” merely the executor of a trust that owned the building. Banca Mifel and Banco BX+ did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

The residents of Puebla 261 did not receive a copy of their investigation file, but prosecutors showed it to them in the office. The prosecutor’s investigation file alleges that Puebla 261 was abandoned and being used, presumably by intruders, for drug dealing: An anonymous complaint for drug dealing in the property was made on February 20, just three days before the eviction.

Without their belongings and homes, denied the chance of building a legal case in their defense, few Mexico City residents have resisted. When the Evicted People’s Network had first contacted now-president Claudia Sheinbaum, then mayor of the capital, in June 2019, the network consisted of residents of 17 buildings, all fighting attempts by third parties to remove them from their homes. The group presented a petition to Sheinbaum and authorities from the local housing institute, the Human Rights Commission and the prosecutor’s office, among others, who formed a working group to address the evictions. The working group and residents developed a rapid-response protocol meant to prevent illegal evictions. But while the government managed to delay some evictions, it could not prevent them, arguing that the autonomy of powers prevented it from intervening in cases in the justice system. The rest, after being evicted, remain empty and abandoned. Sheinbaum’s spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

✺

Thrown out of their homes, the residents of Puebla 261 started knocking on doors and organizing.

On Monday, April 8, the neighbors arrived at the National Palace before sunrise. Inside, then-president Andres Manuel López Obrador would give his morning press conference at 8 a.m. The daily presentation is live streamed on YouTube and watched by thousands, and the neighbors wanted an audience with the head of state. As dawn broke, a posse of bleary-eyed public servants, credentials on lanyards dangling over their sweatshirts, came out to meet the people. One by one, the interlocutors approached the would-be complainants to hear their plights. They nodded sympathetically but made it clear that no one would pass through the palace doors.

A security guard in a padded vest paced back and forth. Inside, all the rooms had holes in the floors. Within just a few days, Puebla 261 had become uninhabitable.

The neighbors, some of whom were on disability leave from work due to injuries sustained during the eviction, brought a printed letter petitioning the president’s intervention. They wanted Civil Protection officials, the authority that oversees risks in construction sites, to stop the illegal demolition. Legally, the seals on the building’s doors indicated that no one should enter, and the construction crew lacked the permits necessary for demolition. A phone call would suffice. The official insisted, though, that they had to go through the prosecutor’s office. He offered to set up a meeting for them the next day.

On Tuesday, April 9, the neighbors showed up early at the prosecutor’s office accompanied by several lawyers. Receptionists and officials shuffled them from one office to another until finally sending them away.

One neighbor managed to negotiate a permit to enter the building to collect her belongings. On Wednesday, April 10, she showed up to find a disturbing scene. A dozen men, dressed in jeans and t-shirts destroyed the walls and floors of Puebla 261 one hammer-blow at a time. Each blow let loose a shower of plaster dust. From a certain angle, peering up into the second-story windows, they glimpsed patches of blue sky where the ceiling used to be.

The official seizure seals hung crooked across the front gate, half-unstuck. Inside the gate, a loose screen prevented passersby from looking in. The neighbors used a twig, inserted through a gap in the gate, to push the net to the side, jerry-rigging a peephole into the front hallway. When they pushed their faces close, they heard the panting of a guard dog. Further down the hall, a shaft of light illuminated another German shepherd, chained up between piles of rubble. A security guard in a padded vest paced back and forth. Inside, all the rooms had holes in the floors. Within just a few days, Puebla 261 had become uninhabitable.

Thursday found the neighbors again wielding hand-drawn signs in the morning light. They made their way to the nearby intersection of Valladolid Street and Avenida Chapultepec, a major thoroughfare through the center of the city, and at 10:40am, they stepped into the street to block traffic until civil protection showed up. Once they noted that the rubble falling out of a second-story window could harm passersby, they stretched caution tape across the front of the building. A Civil Protection official told the security guard through the screen that he was suspending work on the building until the crew installed the necessary safety measures; they made a verbal agreement to cease work for the time being.

The neighbors decided to sit and wait until the workers left the site. An hour passed, and the thuds began again, this time with more force. They peered into the front hallway and saw the ceiling collapse under blows. The passage filled with rubble. Dust billowed out of the windows. They called the phone numbers left by the police and Civil Protection; they called the delegation; they called animal protection. No one answered. No one showed up.

Two police officers accompanied two men to deliver a pizza. From the second floor a window opened, and a rope snaked out; the men tied the pizza to the rope and hauled it into the building. The next day the construction crew returned, this time covering the windows to prevent rubble from falling onto the sidewalk and onlookers from peering inside.

The seals from the prosecutor’s office disappeared by mid-summer. Spray-painted across the mint-green walls reads an order: TOTAL DEMOLITION.