Safe Space

Why does Switzerland have so many bunkers?

APRIL 24, 2025

PHOTO: Remains of an old infantry bunker near the barracks (300 m in direction Schöllenen) in Switzerland. (via Wikimedia)

At first, Zora Schelbert, chief operating officer and tour guide at the Sonnenberg nuclear bunker in Lucerne, Switzerland, wasn’t sure whether the requests she was receiving were a joke. It was February 2022, and Russia had just dropped the first bombs over Kyiv. “People were asking me what kind of measures they should take, where they would have to have to go,” Schelbert explained. She quickly realized they had confused the historical society she works for, “Unterirdisch Überleben” (“Surviving Underground”), for the local department of civil protection.

To the alternating fascination, bewilderment and envy of its European neighbors, Switzerland, population nearly 9 million, has more bunkers per capita than anywhere else in the world — enough to guarantee shelter space to every single resident in the event of a crisis. (Sweden and Finland are a close second, covering all major cities.) The queries Schelbert was receiving came from frightened people trying to locate their assigned places. Today, however, the Sonnenberg bunker is mostly a museum. Originally built in 1971 to protect up to 20,000 people, it remained one of the largest nuclear shelters in the world until 2002, when its capacity was reduced to 2,000 to improve efficiency and reduce costs.

The exposure to war and man-made disaster feels more acute than it has since any other time since the end of the Cold War.

“Of course I took my replies seriously,” Schelbert said, explaining how she redirected concerned parties toward the appropriate point people. “But yeah, then more emails came in. And phone calls.”

Faced with unrelenting Russian aggression and the simultaneous withdrawal of American military and diplomatic support, European countries across the continent are reinvesting in defense. But civilian protection, too — non-military measures for civil defense, including the construction of nuclear and air-raid bunkers — has emerged as a fresh priority. This January, Norway re-introduced a Cold War-era mandate to build air raid shelters in all newly constructed residential buildings — a requirement Switzerland has upheld continuously since 1963. In Germany, which recently passed groundbreaking legislation to finance billions in new military spending, the question of how and whether to build civilian bunkers is once again a matter of active public debate. Partly inspired by efforts in Germany and Norway, in March of this year, the European Union issued official statements urging residents to keep an emergency stockpile containing 72 hours’ worth of supplies on hand at all times. The exposure to war and man-made disaster feels more acute than it has since any other time since the end of the Cold War.

In Switzerland, the redoubled interest in civilian protection is more a bellwether for shifting public attitudes than a sign of an actual change in policy. Before 2022, “the shelters were seen by a big part of the population and even some politicians as unnecessary,” said Daniel Jordi, Switzerland’s federal director of civil protection and training. “And this definitely changed.” Silvia Berger, professor of Swiss and contemporary history at the University of Bern and a leading expert on the cultural history of bunkers, confirmed that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has deeply impacted public perceptions of civil protection: “We’re in the middle of a transformation” of public attitudes “that is not yet finished,” she told me.

Switzerland’s policy to provide shelter to every single resident in the event of a crisis was first enshrined into law in 1963. Every new residential building in Switzerland must either include an on-site bunker, or else developers are required to earmark funds for a nearby public one maintained by the state. As a result, Switzerland is today host to 370,000 bunkers designed to protect civilians underground for anywhere from a few hours to two weeks. Ventilation systems have a shelf life of about 40 years, and neutralize the effects of radiation, nuclear fallout and chemical and biological weapons. The maintenance and construction cost per person, borne largely by developers and property owners, is comparable to annual premiums for Swiss health insurance: Historically, the price per spot is about 1,400 Swiss francs in bunkers with a capacity of 50 to 200, or about 3,000 Swiss francs for smaller ones. In peacetime, most Swiss use them as wine cellars, storage facilities or saunas. In the 1990s, as Cold War tensions relaxed, bunkers even played host to paintball and band practice, or served as community centers.

A second type of bunker — command posts for civil protection and emergency personnel who manage operations — is designed for longer stays, and is equipped with showers, kitchenettes and internet access. In recent years, these command centers have been used, not without controversy, as overflow housing for refugees, asylum seekers and the homeless.

“This is what we wanted,” Jordi said of the bunkers’ extracurricular uses, “a system which is normally used, but when it comes to the worst, you can rather quickly change it into a protected room.” Current regulations require bunkers to be crisis-ready in less than five days. Of the notice period, Jordi explains, “War does not happen tomorrow without any introduction.”

In peacetime, most Swiss use them as wine cellars, storage facilities or saunas. In the 1990s, as Cold War tensions relaxed, bunkers even played host to paintball and band practice, or served as community centers.

My own apartment block in Geneva, where I live, is outfitted with a typical residential bunker, though I didn’t know it was operational until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when the public mood shifted. I heard of friends of friends packing suitcases and stocking up on iodine. (At the cantonal level, Swiss civil protection units are responsible for stocking enough iodine for the entire population at all times to counteract exposure to radiation.) I learned the expression “Chernobyl baby,” an idiom equivalent in meaning to the anglophone, “Your mother must have dropped you on your head.” I went to the basement of my own building, home to over 100 families, to visit our on-site nuclear shelter, currently divided with raw wooden barriers into 10 separate caves, or storage spaces. A painted green door of reinforced concrete, a foot thick (and always propped open), seals hermetically with the help of a torque. There’s a drain in the middle of the floor. My neighbors’ caves are filled with skiing equipment and old cookware. Ours holds suitcases and American electronics not compatible with European voltage, nor likely to be of much use in the event of a nuclear attack. If our lives depended on it, I estimate we could clear it out in a few hours or less.

✺

The entrance to the Sonnenberg bunker is a brisk 15-minute walk from the Lucerne central train station. I arrive on a drizzling Sunday morning and head along the glacial lake, past tourists balancing heavy, panoramic camera lenses, through the cobblestone streets of the historic city center and into the hills that rise above it, until I reach a playground made lush by heavy recent rains. A cement ramp leads along the far end of the park, just beyond the swing set, to a set of heavy gray doors set into the hillside. If you weren’t already looking for the entrance to a nuclear bunker, you could easily mistake it for some far more mundane piece of municipal infrastructure, like a water treatment plant.

About 20 of us are gathered here for a public tour of Sonnenberg organized by Unterirdisch Überleben. Aside from Zora Schelbert, our guide, only five of us are women. A father, here with his 13-year-old son, jokes that interest in nuclear bunkers appears to be decidedly male-coded; his son insisted on a visit after his younger brother came home raving about a school field trip to the facility a few weeks earlier. The family lives in a pre-war home in central Lucerne, which means they have no on-site bunker in the basement. The father admits he has no idea to which public shelter they’ve been allocated. “We’re more of a music family,” he says by way of justification.

In the event of a nuclear attack, traffic would halt, and instead civilians would stream in, sealing off the tunnel entrances with the aid of four concrete doors 1.5 meters thick and capable of withstanding a nuclear detonation at a distance of 1 kilometer.

In addition to the father and son, there are two Londoner tourists with the very broken German of very good sports; an Austrian family of four who’ve relocated to Lucerne from Vienna, and who were drawn to the bunker after seeing a TV documentary; a rowdy group of young friends on a Sunday lark; a middle-aged couple from the nearby town of Aarau; and two attentive Swiss 30-somethings in hiking boots who refuse to speak to me. We’re joined at the last minute by a young Norwegian woman and her elderly father. As we head in, our most committed member, another Swiss man with an expensive-looking camera, volunteers to act as caboose; he lingers behind to take photos, and to confirm for Schelbert that we haven’t left anyone behind as we begin our descent underground.

What we’re visiting today is not the Sonnenberg bunker qua bunker, but rather the former command center — the seven-story, subterranean cement bloc where emergency squads were meant to implement the technical and logistical operations that sheltering 20,000 people underground entails. The original civilian “bunker,” in fact, is no less than the four lanes of traffic whizzing below our feet: An underground highway, the Sonnenberg Tunnel was conceived in the 1970s to ease traffic flow through mountainous central Switzerland, but when construction coincided with national efforts to bolster civil protection, the twin throughways were reinforced to serve a second purpose as emergency shelter space. In the event of a nuclear attack, traffic would halt, and instead civilians would stream in, sealing off the tunnel entrances with the aid of four concrete doors 1.5 meters thick and capable of withstanding a nuclear detonation at a distance of 1 kilometer. The command center overhead stocked a whole town’s worth (450 tonnes) of equipment — including bunk beds, dry toilets, water, and other supplies — ready to be mobilized into the tunnels below by way of dolly carts.

A gallon-sized food tin is labeled, unpromisingly, “Überlebensnahrung” (“Survival Food”). The kitchen and its canned menu were intended for the command staff only; even today, civilians are required to bring their own nonperishables underground.

It’s a tall order to erect a small city overnight: While today’s bunkers are ready for emergency use within five days, and often less, the timeline for Sonnenberg was two weeks. In the one and only trial run, conducted in 1987, emergency squads managed to erect only a fraction of the necessary infrastructure. They were also unable to close one of the four, 350-tonne concrete doors; left ajar, it is unlikely to have been much protection against a nuclear bomb dropped at any distance. The failure fed suspicions over the feasibility of maintaining Sonnenberg at scale, eventually culminating in the local government’s decision to reduce capacity. Still, it remains an exception: Most shelters in Switzerland house anywhere from a single family up to 200 people.

Nor does your typical civilian bunker double as a semi-permanent museum, as Sonnenberg does today. Exhibitions preserving original equipment complement the tour, giving visitors a sense of what life might have been like within the command center during the Cold War. The LED strip lighting, exposed pipes and spotless cement hallways, give the impression of a brutalist prison. We move from floor to floor via sloping ramps originally designed to accommodate carts for delivering supplies into the tunnels below. The kitchen is a row of glistening steel vats, domed tops raised like permers at hair salons, set with ladles the size of human heads. A gallon-sized food tin is labeled, unpromisingly, “Überlebensnahrung” (“Survival Food”). The kitchen and its canned menu were intended for the command staff only; even today, civilians are required to bring their own nonperishables underground.

The original command center was also outfitted with a hospital; the pre-op room contains the only shower in the entire facility. There are tall stacks of dry toilets — glorified gray plastic buckets — of the kind still allocated to shelters today, and which protect against the spread of feces-borne disease; emergency water tanks; and internal phone lines to facilitate easy communication between departments and floors. There are no windows. The analogue clocks on the walls include a little red bulb to indicate whether it’s day or night above ground.

One can’t help but wonder: Is it worth it? In the surgery, the Norwegian man in his mid-70s, here with his daughter, shares that he doesn’t put much stock in the idea that nuclear war is survivable. He reasons that “if the Swiss go underground for two weeks, when they come back out, still they won’t be able to live.” He adds wryly that “the greatest protection the Swiss have is money.” Certainly it’s no accident that Switzerland, with the sixth highest GDP per capita in the world, and his native Norway, with the ninth, have historically boasted some of the world’s strongest civilian protection programs.

More truthfully, however, the efficacy of the bunkers depends on the type and scale of the crisis. The worst of the fallout from an atom bomb typically dissipates within days or weeks, conceivably within the intended length of stay, and when reducing radiation exposure is lifesaving. A meltdown at a nuclear plant the scale of Chernobyl, by contrast, can render the surrounding area uninhabitable for centuries.

The Austrian family also expresses doubts about surviving a worst-case scenario. They point out that while Vienna was even closer to the Iron Curtain during the Cold War, with the Hungarian and then Czechoslovakian borders only an hour away, no comparable infrastructure was built, nor do they wish Austria had followed Switzerland’s path. The family consensus is that there are “better things to spend money on,” and that “diplomacy is more effective.”

✺

Skepticism comes easily to life underground: How will large groups of strangers in great psychological duress cooperate for days in cramped cement cells underground? (One early recommendation from the 1970s — to channel rivalrous or aggressive impulses into card and board games — seems less than foolproof.) What about commuters far from their allocated spaces when crisis strikes? Can hospital patients and the elderly be efficiently ferried to the bunkers that have been built specially for them? And while ventilation systems will protect civilians from radiation, nuclear fallout, or chemical weapons — invisible dangers that simply hiding deep in the London Underground system, say, would fail to counteract — no bunker can withstand a direct hit from a nuclear bomb.

Early propaganda videos and cartoons from the 1950s and 1960s featured the Murmeltier, or marmot, drawn or filmed at peace among alpine wildflowers — then quickly ducking into its hovel at the sight of an eagle or other threat passing overhead.

Nevertheless, the Swiss attachment to universal civil protection remains notable, and the reasons behind it go deeper than finances alone. Bunkers are simply “an integral part of Swiss identity,” argued Guillaume Vergain, Deputy Head of Service for Civil Protection and Military Affairs for the canton of Geneva, and whose job it is to make sure shelters are built to code and at capacity within his jurisdiction. “It’s in our DNA.”

That DNA is inherited directly from World War II, when bunkers were already an established part of Swiss military strategy. In the early ‘40s, when neutral Switzerland was entirely surrounded by Axis powers, the army famously stocked the Swiss Réduit (“National Redoubt”), a series of military fortifications in the central Alps dating to the 1880s, with supplies and ammunition to prepare for a potential Nazi invasion. The paradigm-shifting rate of civilian casualties in air raids elsewhere across Europe, however, proved the need for an equivalent civilian protection program — a kind of “civilians’ réduit.”

The nuclear arms race during the Cold War made civilian protection programs all the more urgent. The result, historian Silvia Berger said, was a new mentality of “total national defense,” including the ideological defense of “core values of Switzerland,” such as federalism, independence, participatory democracy and political neutrality, ideals positioned in contrast to Soviet authoritarianism.

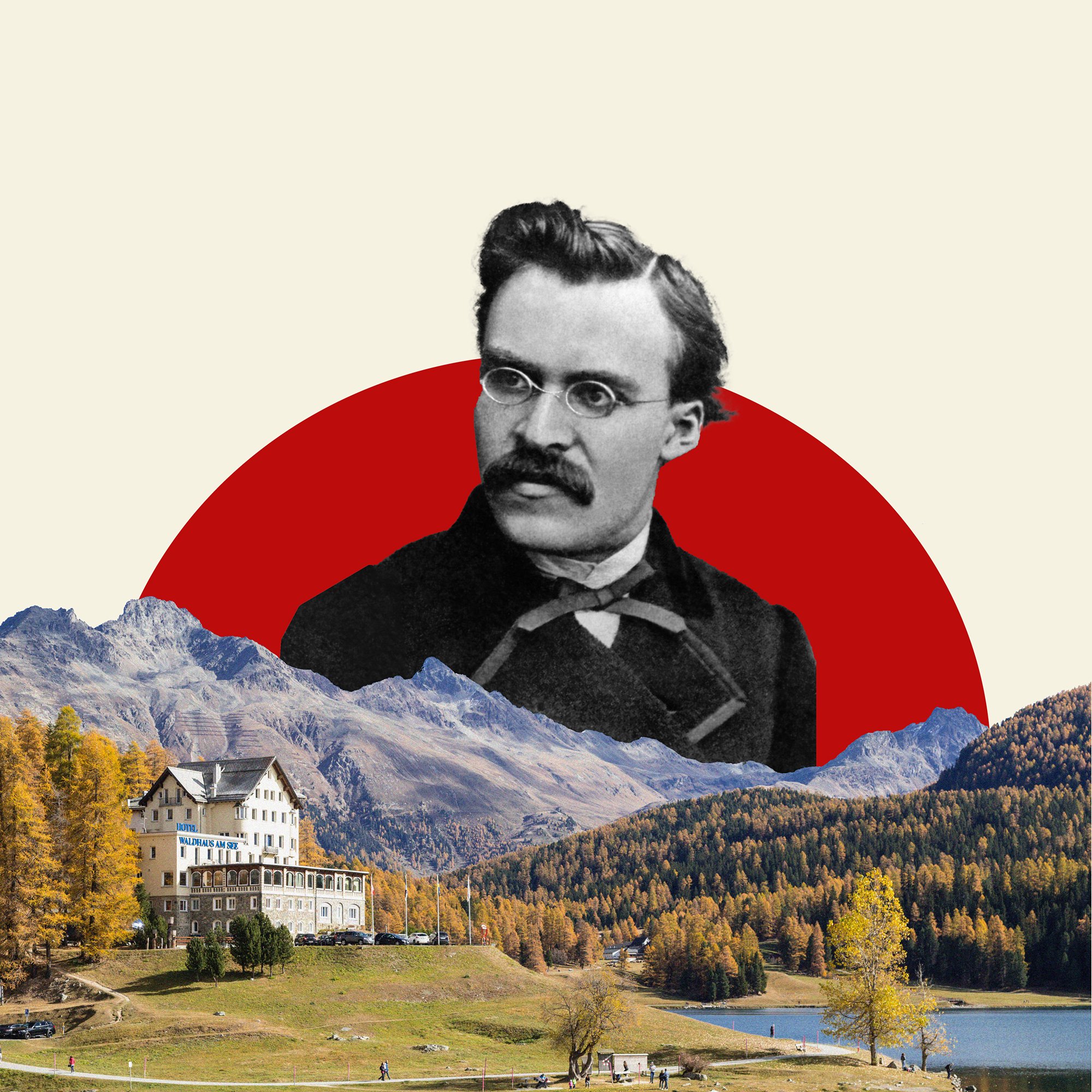

Other cultural factors made bunkers a logical strategy. Compared to the United States, Berger added, where during the Cold War going underground could be viewed scornfully as weak or culturally “un-American,” in Swiss military history, the mountains and the subterranean were always seen as a “safe space.”

To expand access to civilian bunkers, however, the government first had to sell the public on the extraordinary effort; in 1945, only around 30 percent of the Swiss population had access to a shelter. Early propaganda videos and cartoons from the 1950s and 1960s featured the Murmeltier, or marmot, drawn or filmed at peace among alpine wildflowers — then quickly ducking into its hovel at the sight of an eagle or other threat passing overhead. A later video dating to the 1960s, shown on the Sonnenberg tour, features mountain vistas, couples dancing at the disco, and nuclear families sharing a peaceful meal around a red checkered tablecloth. A voiceover acknowledges that while war and crisis may seem “far away” and confined “to the TV,” and that while it may seem as if the worst that could fall from Swiss skies is a “flowerpot” from someone’s window box, the threat of war is in fact all too real.

Shelbert, the guide, has noticed that today visitors to Sonnenberg, once skeptical of the value of maintaining bunkers in a land as peaceful and insulated from crisis as Switzerland, are now more likely to see them as a “privilege,” even a luxury.

Early implementation of the 1963 policy to build shelters in new buildings was met with little protest; in a McCarthyist echo of the U.S., rare critics could be cast as Russian sympathizers or communists. With the rise of the peace movements in the 1970s and 1980s, however, more people began to question whether nuclear bunkers were necessary — or practical. One of the most enduring criticisms is whether bunkers in fact enable nuclear war: What’s to stop countries from using the nuclear option if it is, in fact, survivable? In the late 1980s, sudden, man-made disasters like the meltdown of the Chernobyl nuclear facility in Ukraine in 1986, or the major chemical spill at the Sandoz pharmaceutical plant outside of Basel in 1986, made bunkers seem even more suspect and obsolete, shifting the focus of civil protection from war to disaster preparedness. Along with Finland, Switzerland is also a top exporter of bunker design and know-how, providing plans, construction materials and other expertise that can expose firms to geopolitically motivated critiques: In 2003, at the start of the Iraq war, the Swiss firm Zellweger Luwa, which produces ventilation systems, came under fire for having taken on Saddam Hussein as a client in the 1980s.

The debate has continued to wax and wane according to the public perception of the threats. In 2011, just before a tsunami engulfed the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan, the Swiss parliament had discussed discontinuing the 1963 shelter mandate. After the Fukushima meltdown, however, the existing policy was continued.

The ongoing horrors in Ukraine and Gaza have had a similar effect on public opinion. Shelbert, the guide, has noticed that today visitors to Sonnenberg, once skeptical of the value of maintaining bunkers in a land as peaceful and insulated from crisis as Switzerland, are now more likely to see them as a “privilege,” even a luxury. Public messaging accords with this new attitude. Today, official communications focus on promoting Switzerland’s “culture of preparedness” — and remind the Swiss public that while spending money on shelters is unpopular during peacetime, continual maintenance is essential for readiness in the event of war.

In a small cell crammed with civilian sleeper bunks meant to model how closely packed people would have been in a shelter like Sonnenberg, I duck into a lower berth. It’s as comfortable as a hammock, and more comfortable than a couchette on a night train, made from green mesh slung across metal supports, and complete with a pillow and thick wool blanket. Schelbert urges us to imagine this same space overwhelmed with screaming, crying, terrified people with no more than 1 square meter to call their own. I close my eyes. I can’t.

✺

The entire time I’m underground, it is impossible to shake off a latent sense of the absurd. The planning is exceptional, the engineering impressive; Swiss civil protection services have thought of everything. But to house an entire nation underground for even a few days is akin to trying to colonize the moon: There are so many unknowns that even the most brilliant and thorough plans can easily fail. As, in the case of the Sonnenberg trial run in 1987, they did.

Exiting back into the sunlight, it’s hard not to feel, therefore, that deterrence, diplomacy and nonproliferation are more urgent than ever. Yet supporters of diplomacy are currently fighting a losing battle, especially along the transatlantic axis. When I mention I’m American, one person pulls up screenshots, shown on the local news, of the invasive letters Elon Musk’s DOGE initiative has sent to European universities that have received American grants or funding, with profound ripple effects for researchers in Switzerland and elsewhere. When two visitors decline to speak with me, I wonder, for a fleeting moment, whether it was a mistake to mention that I’m an “amerikanische Journalistin.” Then I remind myself that’s just the paranoia talking — the slow creep of a nationalist strain of thought that conflates individuals with their passports, and which I’d rather resist.

If there is one impression the Swiss civil protection system leaves, it’s that impulsiveness is no way to deal with a crisis, and that the very best civilian protection program is one whose bunkers need never be used. The opposite tack translates to a world ruled by belligerence, unpredictability and close calls — a world of “America first,” where diplomacy is reduced to an outrageous race to press the red button before your enemy can.