Brigades of the Bereaved

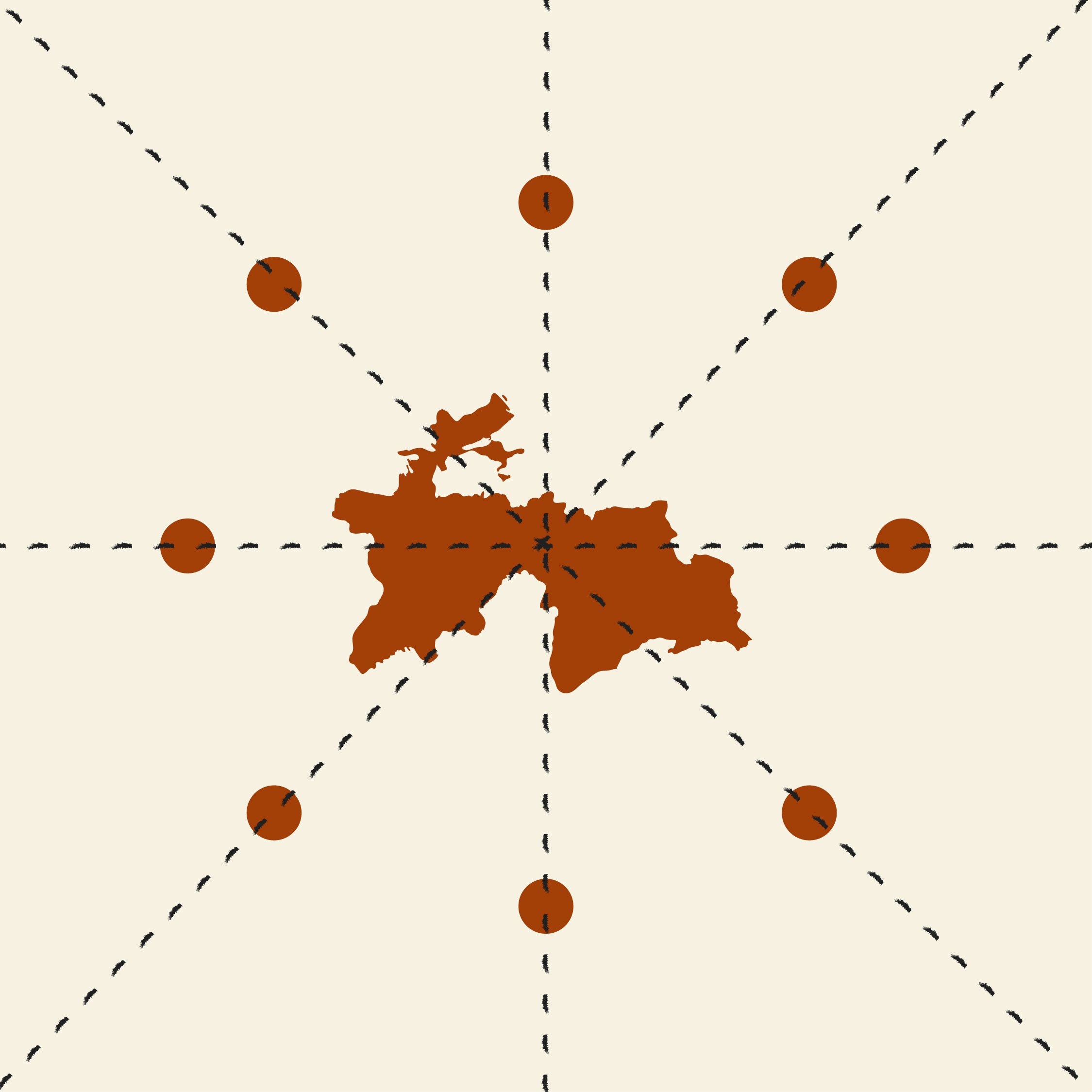

In Mexico, victims of “enforced disappearances” leave no trace; family members risk their lives in search of remains.

MARCH 5, 2024

PHOTO: Armed Mexican National Guard and local officials accompany the Armadillos Rastreadores search brigade as they supervise the unearthing of human remains from an unmarked grave in Michoacán, Mexico, August 2023. (Jared Olson)

On a cloudy morning late last August, in the low blue mountains of Michoacán, along Mexico’s western coast, a dozen people set out in search of bodies. The Armadillos Rastreadores, or “Tracker Armadillos,” as they call themselves, are one of a handful of search brigades that have formed across Mexico over the past decade. Almost everyone in these search parties has had a loved one “disappeared” over the course of Mexico’s 17-year drug war. Finding their remains means learning to identify clandestine graves in unlikely places: abandoned farms; overgrown, bouldered hillsides; derelict garbage heaps. The members of these groups scour territories notorious for violence, risking their own lives in order to recover the bones of the deceased.

Miguel Angel Trujillo, one of the group’s organizers, who is searching for the remains of three of his siblings, receives frequent messages hinting at the location of hidden graves. This past August, the weathered 40-something received a promising tip. Several farmers had found an unsettling scene while clearing untilled land high in the mountains, and an anonymous source, writing from an unknown number, said the spot held a grave. “Don’t tell anyone it was me who told you,” the source wrote. “My father-in-law can’t find out it was me.”

As they prepared to load up their van and set off from the church where they had taken refuge for the night, the members of the brigade discovered that the protectors who had promised to accompany them, the Mexican army and National Guard, were nowhere to be found. The group — composed of middle-aged mothers from Michoacán and surrounding states, several Mexican journalists, a collection of government-linked forensic archaeologists, and the two authors of this piece — would enter a conflict zone disputed by paramilitary criminal groups with only two local police officers to ensure safe passage.

Past a silent village, beyond cattle pastures and agave fields, the brigade left the van at the end of a dirt road and walked to a clearing under the arching branches of an old gray oak. Beneath the tree, the group discovered the rusted springs of a mattress, the stuffing long rotted away, poking out of the ground. Underneath the mattress lay a human femur. Several of the women joined hands in a semicircle and said a soft prayer over the spot — the bone could have belonged to any one of their missing sons, daughters, husbands, wives or grandchildren. There, we waited late into the afternoon for officials from the district attorney’s office to remove the remains, one of the over 100,000 “disappeared” victims of Mexico’s unending war.

But by the time dusk was nearing, no one had arrived, despite the office’s promises over the phone. It was only after the brigade had decided to leave and drive the van down the way we came that we encountered a pickup truck stamped with the seal of the district attorney’s office. Both truck and van stopped on the side of the road. An overseer from the district attorney’s office with a paunch and a pistol at his belt emerged from the truck and proceeded to remark on the group’s recklessness: How could we go up into the mountains with so little protection?

“I’m not going up there now,” he said. “What if they [members of the Jalisco cartel] meet us on the road with 30 guys with AR-15s in six trucks and there are only three of us?”

The next morning, the brigade returned to the same spot beneath the oak. Three army and National Guard jeeps arrived full of troops with automatic rifles. The guns formed a ring around the grave, searching the horizon. Clad in white plastic suits, two forensic examiners from the district attorney’s office exhumed bones, melted skin and bucketfuls of contaminated dirt. Several members of the brigade donned latex gloves and joined the forensic examiners to sift their fingers through mounds of soil, looking for bone fragments. Only later did we realize we hadn’t found any hands or feet.

In 2012, in their coastal village in Michoacán, the Mexican Marines arrived at the family home with local hitmen and state police and took her away at gunpoint. She was never seen again.

A few inches beneath the bones, the examiners found a rotting sack made of woven plastic fibers. Inside, they knew, would be the mother lode, what had once been someone’s torso and head. The remains they had found were laid out on a plastic tarp, the femur and hip bones separated and photographed. The body bag would then be shipped off to a forensic lab, where it would wait alongside thousands of other bags of unidentified remains, another anonymous number added to the tally of mostly poor, mostly young victims lost in Mexico’s forever war — a death toll that critics say is far higher than the government’s official count. But for all the searchers know, the bag may have ended up in the trash.

✺

Since the drug war began in 2006, at least 110,000 people are known to have gone missing in Mexico, according to the government’s official count. So-called “enforced disappearance” has become a ubiquitous tactic used by criminal groups, the state and individuals to hide crimes from view. The Mexican criminal justice system has enabled a tight-lipped culture of impunity in which missing persons reports are almost never investigated. Military jeeps patrol city avenues and remote dirt roads in the name of a war against organized crime while poor and middle-class Mexicans are caught in the middle of the army’s corrupt dealings with local criminal and paramilitary groups. In many areas, military and non-state armed groups are difficult to distinguish from one another, so families are often left unsure whether their loved ones were killed by police, military or cartel actors.

Evangelina Contreras, who has lost three of her six children to violence, is one of the leaders of the Tracker Armadillos and has spent a decade searching for her children’s bodies. The first of her children to disappear was her daughter Tania Contreras Cejas, then 17 years old, who had rejected attempts by a neighbor to recruit her into a sex trafficking network. In 2012, in their coastal village in Michoacán, the Mexican Marines arrived at the family home with local hitmen and state police and took her away at gunpoint. She was never seen again.

Over the past year, Contreras has observed a marked transformation in the relationship between the search brigades and the state, noticeable through instances in which security forces sporadically abandon civilian searchers in dangerous areas for no apparent reason. “One time we were in an area where two people were killed several days before, and security just left,” she said.

At least 20 searchers have been killed or disappeared in the past decade. Just this past month, Angelica Meraz León, from Baja California, and Noé Sandoval, from Guerrero, were killed, and Lorenza Cano, from Guanajuato, was kidnapped from her home, her spouse and son murdered while she was taken. Many brigade leaders, such as Trujillo, are subject to frequent death threats. “I receive death threats every single day, but I ignore them,” he said, showing a threatening WhatsApp message from an unknown number. “I’m still here alive!”

✺

In 2022, the official number of “disappeared” people in Mexico surpassed 100,000. In reality, the six-figure toll may be only half (or some theorize even a fifth) of the real number, colloquially referred to as the cifra negra, or “black toll.” The cifra negra would account for everyone who has gone missing in Mexico since the drug war began in 2006, including those whose families were too afraid to file a missing persons report. Between 2006 and 2019, the number of unidentified remains sent to Mexican forensic labs rose by over a thousand percent, and thousands of these bodies were lost or buried in mass graves as morgues in cities such as Chilpancingo, Guadalajara and Tijuana continued to overflow.

After they are taken, the “disappeared” suffer yet another blow, a process of criminalization via the widespread stigma that they are delinquents who were involved in questionable activity — and ultimately deserving of their fate. Andaba metido en algo, goes the common refrain: “They were involved in something.” But many say this with a nervous shake of the head, betraying this justification as a macabre survival tactic, a way of reassuring themselves that they won’t meet the same unfortunate end: forced into an unmarked car by masked men, never to be seen again.

In the first decade of the drug war, that stigma, combined with the fear produced by enforced disappearances, meant there were almost no organized groups to search for missing loved ones. That changed after the 2014 mass disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa, which catalyzed the formation of organized search brigades across the country.

Since then, disappearances have continued apace, with an average of 9,000 per year between 2019 and 2023. In 2022, numerous prominent nongovernmental organizations released statements criticizing inaction on the part of the Mexican state. The U.S. Government Accountability Office even published a report encouraging Congress to rethink military aid to Mexico, citing the number of the disappeared as evidence that the Mexican government is not sufficiently addressing the drug war and organized crime.

In 2017, with the apparent intention of clarifying the national tally, the government created the National Search Commission to track the disappeared. In late August 2023, Karla Quintana, the head of the commission, resigned without apparent explanation. Several days later, an investigation by the Mexican outlet Proceso revealed that she had left her post under pressure from Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration, which had wanted her to fudge the numbers and fabricate an image of decreasing disappearances. Quintana said in a press conference that she left because of “substantive differences, both in method and in objective.” She estimated that the number of disappeared was 126,000, and said that she suspected the tally López Obrador’s government released publicly the next month would be more than 30,000 lower.

In a press conference, López Obrador accused Quintana of acting in bad faith and conspiring with his political rivals. “They want to compare us to repressive, authoritarian governments,” he said. “They want to accuse us of disappearing the disappeared.”

“They’re sending less security because they don’t want us to do the searches anymore,” Contreras said. “Because if we do the searches, we’ll find bodies, and then the numbers of the disappeared will rise.

In December, the government released its official tally, which announced that 16,000 of the 110,000 people on the list had been located — either their remains had been found or they had turned up alive — since the filing of a missing persons report, thereby making the number fall below six figures once again. López Obrador mentioned this statistic triumphantly in a press conference and accused human rights organizations, including search groups, of being “openly against” his government, nefariously creating a situation in which the tally is higher now than it was under his predecessors. When a search brigade finds remains, usually they cannot be linked to anyone currently on the missing persons’ list, due to the fact that most families are too afraid to file missing persons reports after a disappearance, thereby making the tally rise with every search. “Never have more resources been devoted to looking for the disappeared,” the President said.

Meanwhile, some brigade leaders said they feel that the government’s new frosty attitude and their recent experiences of abandonment by military and National Guard during searches may be connected. “They’re sending less security because they don’t want us to do the searches anymore,” Contreras said. “Because if we do the searches, we’ll find bodies, and then the numbers of the disappeared will rise. So they leave us in positions where we don’t feel safe. Yesterday they told us they wouldn’t accompany us, and we would need to find our own security, but how?”

Last spring, Contreras received a tip that multiple bodies had been dumped in a lake bed in Michoacán. When she called the state district attorney’s office to arrange for security for the search, a representative told her that the office would not cooperate because it did not want to add to the tally of the disappeared. “This same government will let you be killed, or will kill you themselves,” she said. “They are not protecting you, so the only way to feel safe is safety in numbers.”

He said he understood that the perpetrators had to choose between killing and being killed: “I would do it, too, if I were in that life,” he said. “Because [if I didn’t kill] I would pay with my life.”

Contreras is not the only brigade leader who has faced unexpected security lapses during searches in the past year. Ceci Flores, the director of one of Mexico’s most prominent grave-searching groups in the northern state of Sonora, described a scene last spring in which she and her group were left to fend for themselves in an area of Nogales, at the border with Arizona, where they faced a high risk of being shot at or disappeared themselves. The National Guard had promised that it would accompany the group, but it never arrived, nor did it give a reason for its absence. In Sonora, the National Guard has been implicated in recent corruption scandals involving local criminal groups. In Hermosillo, Sonora, in November, the group of 13 searchers was shot at by unknown gunmen, and now many are too afraid to continue their work.

✺

The reasons behind enforced disappearance can’t be reduced to a single formula, and often depend on local conditions. Women murdered by abusive partners, their bodies never found, join the ranks of the disappeared, as do poor people living in areas with coveted land or resources.

Many disappearances appear to be accidents or collateral damage — someone in the wrong place at the wrong time, picked up by organized crime operatives to avoid too many eyes witnessing a criminal act. Gerardo Ramírez’s son, Ángel, disappeared seemingly into thin air in 2021, along with two of his co-workers, minutes after they finished their shift at a Sanborns department store in northern Mexico City.

Other cases are more clear-cut, payback for a perceived affront. In 2020, Sonia Ramírez Flores, a searcher in Michoacán, watched from a window as her husband was carried away in a van, never to be seen again. He was a lawyer representing a farmer whose land had been taken over by a criminal group. When their son, an aspiring lawyer, decided to investigate his father’s case, he, too, was disappeared.

Some searchers have collected evidence that their loved ones were not killed immediately after they vanished but were sent to other Mexican states to serve as laborers for criminal groups, working on farms or as soldiers, or being held captive as sex slaves. Contreras even managed to contact two of her missing children for a period of several months after they disappeared. “I’m OK mom,” read the texts sent from her daughter’s phone. “They’re just taking me to Apatzingán.” Then the trail went cold.

“Disappearing” people as a way of enforcing social control and hiding crimes first appeared on a large scale in the 1970s, during Mexico’s “dirty war,” when the military disappeared several thousand student leftists, peasant organizers and upstart guerrillas.

Trujillo and other brigade leaders know where to look for bodies because they receive tips on social media, oftentimes from the killers themselves. He said he understood that the perpetrators had to choose between killing and being killed: “I would do it, too, if I were in that life,” he said. “Because [if I didn’t kill] I would pay with my life.”

✺

“Disappearing” people as a way of enforcing social control and hiding crimes first appeared on a large scale in the 1970s, during Mexico’s “dirty war,” when the military disappeared several thousand student leftists, peasant organizers and upstart guerrillas. The practice was later outsourced to criminal groups in the ’90s and early 2000s, when former officers and deserters from the military began selling their skills to drug trafficking networks. In the violent chaos of today’s drug war, both state and non-state armed groups engage in this tactic to sweep bodies under the rug.

Enforced disappearances skyrocketed after 2006, when former Mexican President Felipe Calderón deployed the military to the streets, ostensibly to fight drug cartels, as part of the war on drugs, an offensive supported by over a billion dollars in U.S. security aid. From the outset, it was clear that the operation entailed human rights abuses. In cities such as Juárez, commandos busted in doors, torturing, executing and disappearing people labeled as malandros: criminals, undesirables or street urchins. At the same time, state agents cultivated rapports with criminal syndicates and their paramilitary wings, making use of them one week — slicing quotas from their profits, using them to wipe out other gangs, or delegating to them the task of disappearing malandros — before exterminating them the next.

Mounting evidence over the past decade and a half has suggested the presence of a systematic state-criminal nexus — one in which state security forces negotiate pacts with criminal factions, allowing them to operate in exchange for money, and in some cases directly protecting or fighting alongside them.

Starting in 2019, the story told to justify this war — that the government was working against organized crime instead of taking part in it — dissolved amid accusations that Calderón and his former secretary of public security had given preferential treatment to the criminal network most people know as the Sinaloa cartel. But the damage was done: Disappearances have continued to rise, and to this day, military and police forces are accused of disappearing and killing people.

In 2018, López Obrador campaigned on de-escalating the drug war. Yet when he was elected, he did the opposite: He gave more funding to the military; granted it control over ports, airports, trains and mega-projects; attempted to dissolve the ostensibly civilian National Guard into the military; and pushed for troops to remain in the streets until 2027.

Mounting evidence over the past decade and a half has suggested the presence of a systematic state-criminal nexus — one in which state security forces negotiate pacts with criminal factions, allowing them to operate in exchange for money, and in some cases directly protecting or fighting alongside them. In local contexts, police and criminal actors often know one another and sometimes even grew up together, facilitating back-door deals and creating an environment where state and non-state groups are truly two sides of the same coin. In state and national contexts, military and National Guard officials accept bribes from organized crime groups, knowing they will likely never be prosecuted, and can safely pocket the money.

In 2020, Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos, who directed the Mexican military from 2012 to 2018, was arrested by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration under accusations that he had accepted bribes and used his institution’s power to protect the Sinaloa cartel. A month later, through murky negotiations between the U.S. and Mexican governments, he was released to Mexico, where he has faced no charges. In 2023, a protected witness alleged that members of the 27th Infantry Battalion gave weapons to the Guerreros Unidos criminal group, accused of disappearing 43 students in 2014. Years of journalistic investigations have suggested that the military was the intellectual author of that crime.

Multiple local residents of regions affected by violence told The Dial that in Michoacán, collaboration continues between state security forces and criminal groups that have been implicated in enforced disappearance.

In the coastal town of Aquila, two hours south of where we joined the Tracker Armadillos, residents said that a yearslong wave of enforced disappearances is connected to the expansion of mining interests, and is carried out by criminal groups with the de facto green light of the military. Though the criminal factions presumed to be behind disappearances have come and gone, two residents — who asked to remain anonymous for security concerns — said the military and National Guard continue to allow those factions to operate, at times even protecting them. On multiple occasions, they said they’ve witnessed trucks full of soldiers or National Guard members casually and unhurriedly drive past their village on the narrow valley road just a short distance behind trucks full of gunmen for criminal groups. “They protect them,” one of the residents said. “There’s complicity.”

Enforced disappearances have become such an intractable crisis in part due to the institutional culture within the military and police, which allows officials to use their power to instrumentalize and co-opt criminal networks. “It isn’t just organized crime pushing into the state,” said Falko Ernst, a researcher with the think tank International Crisis Group who has spent over a decade interviewing soldiers, police officers and hitmen in Michoacán. It’s also the reverse, he explained: State actors seek out these arrangements for money and control.

“No one wants to have a disappeared child, or five. … He should put himself in our shoes for a second to understand the magnitude of the problem,” Flores said.

“Imagine it’s like a layer cake,” said Romain le Cour Grandmaison, another researcher who has investigated conflict in Michoacán for over a decade. “You can’t have organized crime without political protection. Super-local arrangements end up piling up — that’s how the state works.” It’s not just that the state sanctions criminal networks involved in human rights abuses, he said: There’s a violent instability inherent to the overlapping agreements between different state and criminal actors. A National Guard commander might pass weapons to one group of hitmen, for example, while a military lieutenant protects another faction of a competing criminal group, and the state police are intermixed with another. Trust breaks down as new agreements are made and former allies become enemies, leading to recurrent outbursts of warfare. People like Contreras’ children and Trujillo’s siblings end up caught in the crossfire.

✺

After the government’s tally was made public in December 2023 and López Obrador accused search brigades of being “against” him, Flores, the brigade leader from Sonora, said in a video on Facebook that she does not agree with the statistics offered by the government. The investigators did not make their data public, so no outside actor could fact-check their work, and several prominent brigade leaders found their loved ones’ names mysteriously missing from the updated list. “Why say that searching mothers are just government opposition who want to increase the number of the disappeared?” she said. “No one wants to have a disappeared child, or five. … He should put himself in our shoes for a second to understand the magnitude of the problem,” Flores said.

Facing a government increasingly at odds with their work, search brigades have reacted in various ways to the turned backs of the military and National Guard. “In terms of security, they just keep introducing more and more obstacles,” Judith Godínez, a searcher in Michoacán, said. Some family members of the disappeared see accompaniment as a nonnegotiable requirement, but many searchers have vowed to continue looking for the bodies of their loved ones, no matter their own personal risk.

Ceci Hernández, a mother who began searching for her son, Kevin Saéz Hernández, in 2023, is determined to find his body. “You try so hard, you work so hard to give your kids everything, but you can’t keep them safe,” she said. “I wanted to go to the U.S., but now I won’t leave Michoacán until I find my son.” When he vanished in 2022, her son was wearing a necklace of sentimental value, so she sweeps the dirt around every grave, looking for a hint of gold.