Butcher Ding

“I never expected that tai chi sword would become a special type of physical therapy for me.”

AUGUST 22, 2024

I had never thought about taking up the sword; the word “sword” always made me think of unconventional individuals with extraordinary abilities. The swordsmen and swordswomen in literary chronicles are not only proficient in swordsmanship but also capable of incredible feats, such as leaping across rooftops and scaling walls. Some of them are even skilled in sorcery and can use poison to melt bones. Swordsmen and swordswomen are respected because they uplift the weak and overthrow the strong, but in fact, most of them are merely assassins, ancient “terminators” (like in the science-fiction film), loyal only to their masters.

I finally took up the sword because of my instructor. After I underwent surgery, my friends urged me to learn tai chi, so three times a week, I went to a seaside athletic field relatively far from home to study with a tai chi practitioner. It was a class with more than ten students, including young people in their twenties and even elderly people in their seventies — surprisingly, women made up half the class. The instructor arrived early. While others were reluctant to leave dreamland, he’d already been demonstrating his sword and knife skills on the field. The early arrivals could witness his martial prowess. His knife techniques were swift and fierce, stirring up the air with swishing sounds; when he wielded the sword, however, it seemed to carry a blend of strength and softness, a unique gracefulness. If the sword were gendered, as French words are, it probably would have originated as masculine and gradually turned feminine, in contrast to the knife.

Some of my classmates wanted to learn other, additional martial arts after studying one set of tai chi forms for half a year—every class simply involved repeated practice. The instructor was pleased and willing to teach us after class. Anyone who had time to stay could learn at no extra charge. The majority of those wanting to learn the sword and knife were women. The instructor said women were particularly well-suited to learn the sword for two reasons: One, it was elegant, and two, it wasn’t overly intense. And so, I started learning the sword, move by move. Tai chi boxing and tai chi sword were originally the twin sisters of Chinese martial arts. If I didn’t perform well, it became a gentle exercise, but done beautifully, it was a dance.

I never expected that tai chi sword would become a special type of physical therapy for me. After my surgery, my arm and ribs would swell, which could only be alleviated through constant movement. After studying tai chi for half a year, I could move my arm freely, but sometimes it still swelled up. Surprisingly, practicing with the sword helped heal the swelling. A few times when it rained and I couldn’t practice, my arm gradually swelled up again. From then on, I didn’t dare to neglect it and was diligent in my practice, and feeling great.

When the Tang poet Du Fu was five years old, he watched Lady Gongsun perform a sword dance in the Jiangnan region. Fifty years later, he saw her apprentice, Twelfth Lady Li, perform in Sichuan. “Sword dance” is the name of a type of martial dance. Did they hold swords in their hands? It seems like there are swords, and double-edged swords at that, casting intertwined and intermittent glimmers of light in Du Fu’s poem:

Flashing like a thousand suns shot down by Archer Yi Lofty like a group of gods soaring with dragon teams Advancing like a thunderbolt rumbling with rage

Halting like the streams and seas freezing into a clear gleam

Du Fu truly wields the pen like a sword, then uses the sword to elicit the feelings of the individual and even of the country. As the scholar Wang Sishi says: “Seeing the sword dance recalls past wounds — ‘bringing up matters evokes deep feelings.’” However, Wang Sishi then concludes: “Otherwise, it’s just a dancing girl, hardly worth shaking his pen over.” There are always such interpretations full of bias.

No matter how early I got up, there was always someone doing morning exercises in the park, always someone who had arrived earlier than me.

There seem to be no images of sword dances in ancient Chinese paintings. However, there is a North Korean woodblock print where, upon closer examination, what the woman holds in her hand appears to be not a sword but a knife, single-edged, kept close to the body; conversely, the sword is double-edged and must be wielded away from the body — otherwise, you could easily cut yourself. The Qing dynasty artist Jiang Rong did paint a noblewoman performing a sword dance, but unfortunately, the long sword hangs from her waist and isn’t held in her hand at all. In fiction, there is a woman named Zhao from the Wei and Jin dynasties who is skilled at wielding the sword. The text doesn’t specify what type of sword she uses, but even with a bamboo stalk she is able to showcase her exceptional abilities. Swordsmen and swordswomen in modern novels often use flying swords, which can even give off light — gold, silver, blue, and yellow. The depth of the swordsmanship can be discerned by the color of the light. Swordsmen and swordswomen can also fly with their swords, which would make a great scene in a science-fiction film. In the park at night, I often see a man demonstrating the sword, flashing silver in the moonlight. On the evening of the Mid-Autumn Festival, the park is at its liveliest, with many children brandishing battery-powered lightsabers and reenacting The Empire Strikes Back, the last sword dance of the twentieth century.

Of the sword dances I’ve seen, the one I admire the most is from a video recording of the opera Farewell My Concubine, in which Mei Lanfang dances with a pair of swords that flit like butterflies. The two swords are adorned with long silk tassels, which makes it more difficult, because if the dance isn’t performed well, the silk tassels can become entangled, locking the swords in place. I didn’t have a precious sword — all I had was a series of rusty iron pieces that could be extended or shortened at will. The advantage was that my sword was easy to carry, just like a retractable umbrella. Carrying a long sword on the street is an extremely conspicuous affair. A modern-day General Han Xin might face fewer humiliations from thugs, but might also be stopped by the police and asked for identification, accused of carrying a dangerous weapon.

Every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday I went to the distant athletic field by the sea to practice the sword with my instructor. The other days, I practiced on my own in the park near my building. No matter how early I got up, there was always someone doing morning exercises in the park, always someone who had arrived earlier than me. If there were military roles to be assigned, I certainly wouldn’t have played the part of the famed strategist Zhang Liang. When did these early birds arrive? Four or five in the morning? Sometimes a group of teenagers hung around the park, huddled together and leaning against tree trunks, with their soda cans and plastic water bottles strewn all over the ground. They weren’t early birds but rather nightingales who hadn’t returned to their nests the previous evening, having spent all night in the park.

Early mornings in the park, there were very few young people and not a single child. The majority were elderly people, several doing gentle exercises together, seven or eight practicing a simple form of boxing. There were also those who jogged at a leisurely pace, faces glistening with sweat and panting, which made me concerned for their well-being. Of course, exercise is beneficial, but strenuous exercise may be harmful to the body, especially for those over the age of forty. Most people in the park were around sixty, their hair white. Some walked, and some did deep-breathing exercises, making me feel peaceful and serene.

Take me, for example: Who could tell I was a cancer patient? People are like this, neglecting their health in their daily lives, but once they fall ill, they panic and focus on exercising.

In addition to the elderly, there were quite a few sick people in the park as well. Every day, an elderly woman in a wheelchair was brought to the park by her son and daughter-in-law. Because they came every day, they were familiar with many people. The group of women who did gentle exercises often chatted among themselves: What a dutiful son — she must have accumulated good karma over many lifetimes. Another added: It’s rare to have such a virtuous daughter-in-law. Then they shared stories about their own family affairs — children, daughters-in-law, and the like. The wheelchair would enter through the park gate, be rolled toward the other end of the flower-lined path of the athletic field, and stop. The elderly woman, supported by her daughter-in-law, would get out of the chair and take careful steps.

It was evident that the person in the wheelchair was ill, but illness isn’t always as clear as day. That person who holds the “golden rooster standing on one leg” stance for a full five minutes might have kidney problems. This overweight middle-aged person, bending over with their protruding belly, might have heart disease. Take me, for example: Who could tell I was a cancer patient? People are like this, neglecting their health in their daily lives, but once they fall ill, they panic and focus on exercising.

There were also people practicing tai chi in the park. With just one move such as “cloud hands,” you could probably determine which school of tai chi they belonged to. No matter the school, I always watched for a while. This person’s movements were jerky, like the stop-motion dance of a wooden puppet. This person flowed smoothly and seamlessly, reminiscent of a graceful ballet dancer. I was a beginner. I knew my own performance wasn’t up to par, but where else could I practice, if not in the park? I had to hide in a secluded corner to practice. It was hard to escape the public eye, but I didn’t mind. It occurred to me that Lady Gongsun was also a folk dancer, performing on the streets and in the squares. With such impressive skills, of course she attracted a crowd of onlookers, some seated, some standing, and thus in the eyes of young Du Fu “the spectators were like mountains.” A set of tai chi, if performed quickly, took twenty minutes; if slowly, half an hour. I always performed it slowly: I had no choice but to go slow, because if I were to do it any faster, I’d easily lose my breath.

After I finished, I’d take a break for a bit, then practice the sword. Since I started learning tai chi, every time I went to the park, I carried more and more things. At first, I went empty-handed, then I carried a small cloth bag with a light jacket inside, and gradually I added an umbrella, then later a thermos of water, and finally, a sword. Not to mention the towel and wallet in my pockets. Each time I arrived at the park, I found a suitable spot, then hung my small cloth bag on the chain-link fence.

After I finished exercising, I was in no hurry to go home. It was so early, what would I do at home — go back to bed? No, taking a stroll in the park was much better. The azaleas were in full bloom, a swath of purple, pink, and white along the fence, singing of the brilliant spring day. Bit by bit, the sky would become brighter and whiter, the sun would emerge, and soon light would shine on the treetops, marking another clear day. At this time of day, the air was the freshest, the flowers and grass emitting sweet smells. I took a walk along the small path between the bushes, letting my lungs soak it all in.

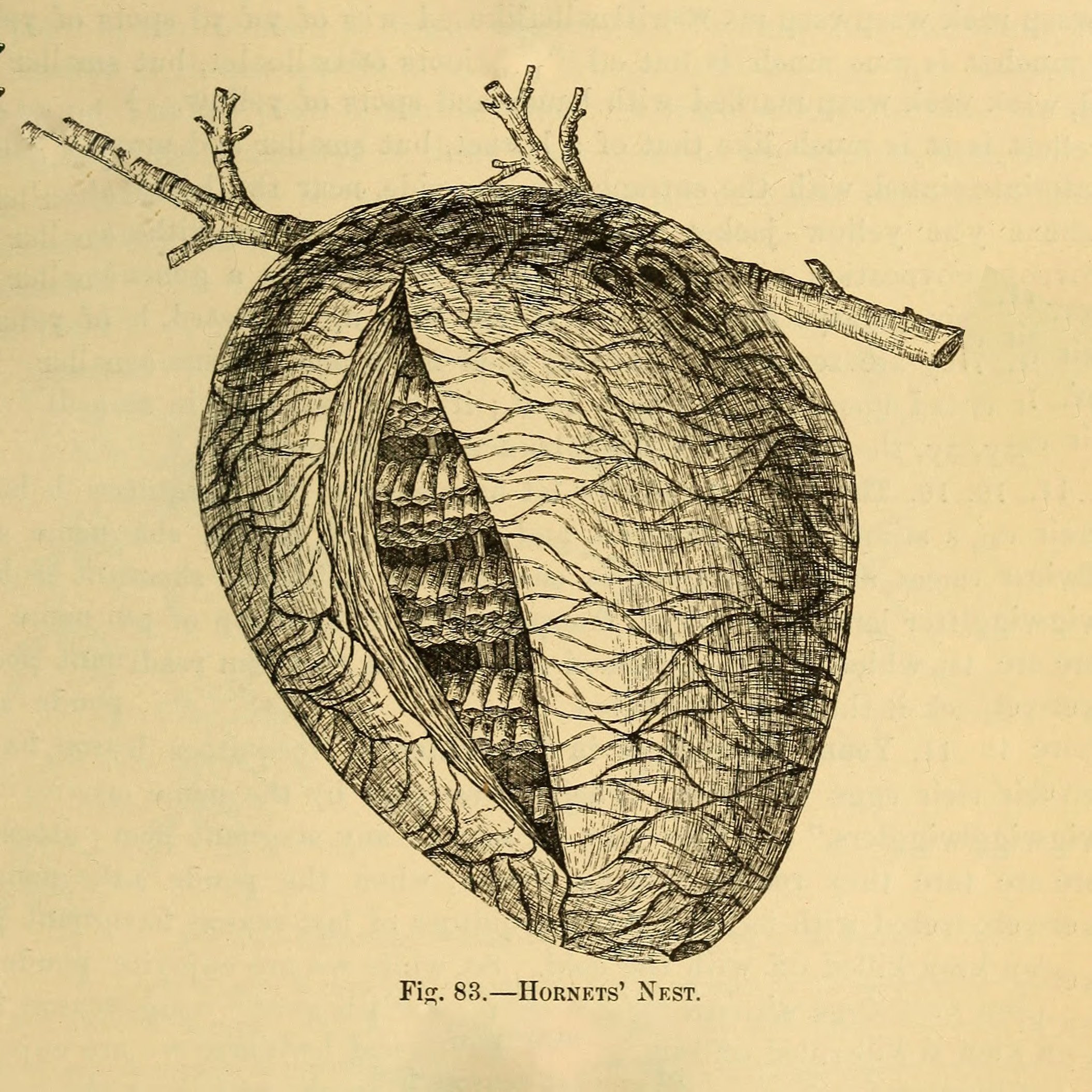

Across the road at the back of the park, there were two sets of buildings with completely different appearances. The one on the right was more than ten stories tall. It wasn’t a residential building, but instead consisted of two huge gas drums, black cylindrical structures, with steel ladders positioned beside them that curved and spiraled upward, much like a maze in a picture. All day long, the drums emitted a heavy mechanical noise, groaning like a wounded beast even into the night. Once it was dark, the ladder paths were lit by rows of vertical and horizontal white neon tubes, casting a ghastly pale light.

To the left of the gas drums, there was a row of silent low-rise buildings, just two or three stories high, grayish-yellow in color. This presence was accompanied by an odor, a murky, foul stench that persisted over the years, as though the smell were a tangible, transparent object. Nearby residents lived with this odor. The row of low-rise buildings that occupied half of the long street was the government slaughterhouse. The gas drums and slaughterhouse were tall and short neighbors, seemingly unrelated, but they subtly echoed each other. Standing on the park’s lush green grass and gazing into the distance, the drums reminded me of the gas chambers of the Nazi concentration camps during World War II. People deemed “inferior” and “impure” were marched into the gas chambers one by one, and transformed into wisps of smoke; such slaughter was nearly devoid of any trace of blood.

I don’t know how cattle are slaughtered in the slaughterhouse. Nepalese Gurkha soldiers slaughter cows during New Year celebrations, beheading them with curved daggers, an occasion to flaunt their heroic prowess. I believe there are no such warriors in the slaughterhouse. The slaughterhouse kills numerous cattle on a daily basis. It is said that they use guns to shoot the cattle in the head, then hang them on moving hooks for bloodletting and butchering. The internal organs are displayed beside the hanging cattle carcass from which it came, for the health inspectors to check. Those that aren’t diseased will be taken to the market to be sold. I heard about a new machine that strips the entire layer of skin from the cow that’s placed inside it, spitting out bloody beef. I dare not imagine what the beef looks like. At street corners and the ends of alleys, there are snake shops, and in the markets, frogs, partridges, and softshell turtles, stripped of their skin and still wriggling ceaselessly. There are always people from the older generation who make up strange stories, saying a butcher was mistakenly rolled into a machine, skinned alive, and spat out.

Likewise, I have no idea how to slaughter a pig. I only know the traditional method, where a pig is tied to a wooden stool, and the butcher strikes with a knife, splitting open the pig from its throat all the way to its belly. Naturally, there are also rumors about the butcher who accidentally cuts open his own intestines. It’s all a misfortune of life. Standing in the park, separated from the buildings by the roaring traffic on the road, I never heard gunshots ring out from the slaughterhouse, nor the howls of pigs and cattle. Did residents who lived near the slaughterhouse hear these things? Presumably not, as it appeared there were no complaints from readers in the letters to the editor of the paper or on the TV program Citizen Voices. So then, slaughtering thousands of animals in broad daylight was a quiet business. My friend who loves cats wrote that the most tragic film, to her mind, is Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar, inspired by Dostoyevsky. In the end, after the donkey is shot, it shudders and walks into the midst of a flock of sheep, sitting there quietly, with the sky above and the earth below; it silently awaits its final moment. She watched the film twice, always wanting to cry out loud, but was unable to do so. Whenever she thought about it, the ending still pained her. The towering gas drums were black, while the side of the slaughterhouse facing the park had eroded to a dirt-yellow color over the years. Every day it was washed, water gushing out, all the slaughter seeming to spread continuously from the darkness in every direction.

If the world were divided only into two categories, those who slaughter and those who are slaughtered, I’d still choose to be slaughtered.

Standing in the park one morning, I saw an unusual sight: a cow and calf taking a stroll on the grassy slope outside the iron fence of the slaughterhouse. The cow stood there dazed, while the calf wagged its tail, bowing its head to graze. What a heartwarming pastoral im- age of mother and child. Who would know that on the other side of the iron fence was a slaughterhouse? Life and death were separated by a mere fence. The cow was probably brought to the slaughterhouse already pregnant and was permitted to give birth, resulting in the calf, but would this change their future fates?

There is a saying that cows cry when facing their executioners. It seems that such incidents have also happened in the slaughterhouse. A cow being led to slaughter charged out of the narrow road and ran into the courtyard. No matter how much it was tugged and pulled, it refused to budge, and suddenly the cow knelt down and shed tears. The slaughterhouse staff all said: Just spare this one. But the boss didn’t agree. This was a slaughterhouse, not a pasture; they continued leading the cow up the sloping narrow path, and it wasn’t long before the cow was suspended on the hoist, slowly gliding down. There’s more to the story: Things didn’t go so well in the end for the boss. Of course, some cows are lucky. A while ago, there was another crying cow, but it was pardoned and sent to a Daoist temple to live out its remaining years, and it even became an attraction for visitors. The writer Qian Zhongshu once joked that doctors are also a kind of butcher, but in my opinion, sometimes butchers are also doctors.

Spanish bullfighting is really and truly bulls fighting. It’s bulls resisting the curse of their fate, the struggle of life. The bulls cannot vanquish the spears, swords, and various opponents who take turns wearing them down, and they die having exhausted their strength. Ordinary cows have no room for a final battle and can only await their inevitable demise. Do the cows destined for slaughter possess a sixth sense? No one cares about the cows’ feelings. If the world were divided only into two categories, those who slaughter and those who are slaughtered, I’d still choose to be slaughtered.

In Zhuangzi’s writing, the cow is almost invisible. What we see is Butcher Ding. Zhuangzi says that after he perfects his skills, he doesn’t need to use his eyes to see the cow. He understands it intuitively, relying on the principals of nature, following its inherent way, slaughtering a complicated cow with ease, like a cellist playing a concert with closed eyes. It’s strange — while I was lying in the operating room, seeing the surgeon donning a white robe and green cap, I suddenly thought he was Butcher Ding. I also finally grasped the second half of Du Fu’s line “the spectators were like mountains, their color sapped away.” Was he an ordinary butcher who replaced his knife every month, or a skilled butcher who only replaced his knife once a year? In his mind, was I a person, or was I just a tumor?

Waiting in the hospital bed for nearly fifteen minutes, all I could think about was butchering a cow. The doctors and nurses all showed up early, but the anesthesiologist was missing. There must have been a traffic jam — he charged in fifteen minutes late. This time, I saw the anesthesiologist’s appearance: He was short and stout, like the actor Cantinflas in the film Around the World in 80 Days. Ah, Passepartout was present — we could start the show.

Beforehand, the nurse had applied adhesive tape to my legs and helped me slide out of the sleeves. I heard the doctor request a “drip pan,” using the English words. I didn’t know what that was. Once the anesthesiologist arrived, the surgery began soon after. I wasn’t the least bit afraid. I only heard the anesthesiologist say: I’m going to give you anesthesia, and you’ll sleep for a while. I said, Okay. He injected the needle with the IV into my wrist and placed an oxygen mask on me. I took a few breaths, still aware of everything. Someone drew a map on my chest. Something was icy cold — possibly the medicine. Oh no! They were going to cut open my chest, but I was still conscious! I wanted to speak, but I couldn’t make a sound. I tried gesturing with my hands and feet, but my hands and feet didn’t get the memo and wouldn’t move. Everything failed. And so, I tried blinking my eyes to indicate that no, no, I was still conscious. Whew, they hadn’t started operating at that moment. When I blinked again, I was already lying in my hospital bed. It was four hours later. The surgery had taken two hours.

Who invented anesthesia? It’s nothing short of a lifesaver for patients. Think about the immense courage and endurance it takes for Guan Yu to endure bone-scraping treatment in the historical novel the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, or for Cao Cao to have his head opened and brain operated on, but this of course is all in the realm of fiction. However, the real-life Hua Tuo invented the powdered anesthetic mafeisan more than seventeen hundred years ago. He had his patients ingest it with alcohol and fall into a deep sleep before performing surgery on them. How remarkable. When the anesthesia took effect, I didn’t feel anything at all. Was this what death is like? Well then, perhaps death is an extremely comfortable thing. If a person can depart in such a way, what’s wrong with it? Some time ago, there was the unfortunate case of a patient who died during surgery due to the incorrect use of an oxygen tank. I think that if I were in that situation, I wouldn’t feel regret; having no feeling would be much better than feeling anything, because once you start to feel something, it’s mostly pain.

In the operating room, for several hours, I had no awareness at all. During this time, the doctors and nurses must have been busy: sterilizing the skin, making an irregular fusiform incision around the breast, first cutting the epidermis and then cutting the dermis, separating the skin flap, clamping the subcutaneous tissue with hemostatic forceps, covering and protecting the skin flap with moist gauze pads, cutting and ligating at the same time, dealing with veins, arteries, and nerves, cutting off the pectoral muscle, dissecting the axillary vein and removing the axillary lymph nodes, cutting the breast tissue, removing the surgical specimen, stopping the wound from bleeding, thoroughly irrigating the wound, inserting a drainage tube, connecting a negative pressure suction tube, then suturing the skin. Ah yes, the patient’s condition was very good — no need for a blood transfusion or skin grafting.

In the operating room, was the doctor cutting and slicing with his scalpel in silence, focusing on the task at hand, or was he talking and laughing, in an almost dance-like rhythm? My hunch is he was talking and laughing. Amputating a breast is not major surgery. There aren’t a lot of intestines involved. My younger sister also had a small tumor. It was benign, and as it was only a minor procedure, she didn’t need anesthesia. She kept her eyes open and watched the doctor perform the surgery, witnessing the blood, needle, and thread through the mirror, how the doctor sewed stitch by stitch, tied a knot, sewed again, then tied another knot. My sister is gutsy — I’m sure I wouldn’t have dared to look.

Did the doctor who operated on me also love music? We were such strangers to each other — he didn’t know me, and I didn’t know him, yet my life was in his hands, and I had to trust him. What went through his mind while he was performing my surgery? In his eyes, was I a whole cow, or just some cow bones, tendons, and flesh?

My friend told me that when he was a child, while goofing off playing soccer, he fell and split open his lip. He went to the doctor and received five or six stitches, without any anesthetic, simply observing the doctor and nurse chatting about weekend programs while stitching him up, a single thread, pierced downward, pulled out, drawn across, bent down, making a stitch, tugged taut. My friend became a leather shoe. He believes that if a surgeon were ever to lose their job, they could easily change careers and become a cobbler.

Our family doctor, who’d emigrated and wouldn’t return for half a year, might be surprised to see my condition. He’d treated me before he left. Other than slightly high blood pressure, I’d still been in fairly good health. In medical school, our family doctor studied both internal medicine and surgery, but he rarely performed surgical procedures, almost never, because he was left-handed and found it inconvenient. He enjoyed playing the piano in his free time, going to the horse track on weekends. When he performed surgeries, what went through his mind — which horse would cross the finish line first, or the steady rhythm of baroque music?

Many doctors are fond of music and can play an instrument or two. Recently, a group of music-loving doctors formed an orchestral group. Because they didn’t have a flute player, they only formed a string ensemble, actively practicing “Greensleeves” to raise money for patients in Nam Long Hospital. Hearing the name Nam Long Hospital is alarming for cancer patients, as it’s a convalescent hospital for patients with terminal cancer. Although it’s referred to as a place for convalescence, in reality, it serves as a gateway to another journey: the afterlife. For terminal cancer patients, doctors often have nothing left to say, so they pay tribute with music, raising funds for the hospital, making patients’ journeys a little more comfortable. This also provides additional funding for the research center to help save those who are sick and those who may become sick.

Did the doctor who operated on me also love music? We were such strangers to each other — he didn’t know me, and I didn’t know him, yet my life was in his hands, and I had to trust him. What went through his mind while he was performing my surgery? In his eyes, was I a whole cow, or just some cow bones, tendons, and flesh? The anesthesia was truly marvelous. When things turned gory, I was suddenly absent. For me, surgery was just like Zhuangzi’s tale “Essentials of Nourishing Life,” about Butcher Ding cutting up a cow — I saw only Butcher Ding but not the cow. Before I had a chance to see or feel the blade, the doctor had wiped it clean and safely stored it away. After writing about Butcher Ding, Zhuangzi went on to write fifty words about the one-footed Commander of the Right. I used to think that this was a disjointed style of writing. What was the connection between butchering a cow and a limping foot? Reading it now, I feel I have a deeper understanding than others might. Wholeness or deficiencies of the physical body, regardless of whether innate or human-made, indeed do not matter.

Was the cow that Butcher Ding cut up a living cow, its four feet bound, unable to move? Was it conscious? At that time, of course, there was no anesthesia. Did the cow cry out? Zhuangzi didn’t address these details. In the writings of this philosopher who saw unity with all things, the cow is inevitably an objectified alien being. As for the bull in the bullfighting arena, it certainly suffers. The mountain-like spectators can see the bull’s struggles. The cruelty of bullfighting lies not in the bull’s fated death but in the prolonged process of suffering. Where are the voices of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals?

Sunlight shone down on the grass. It was another clear spring day. Hallelujah, I was still alive. I carried the small cloth bag home, the iron sword clanging inside. Might the sword of decisive battles and the sword used to pierce bulls someday become part of a national sword dance?

This text is an excerpt from Mourning a Breast by Xi Xi (First published in English by New York Review Books, Translation Copyright © 2024 by Jennifer Feeley)

✺ Published in “Issue 19: Fiction” of The Dial

Photo: Freepik