Hornets

“Hornets are trying to live too, making their nests. Humans have inside them envy and cruelty and pride and so on and hornets, well, they have a bit of poison.”

AUGUST 22, 2024

-

One of Kerala’s contemporary economic phenomena is the migration of semiskilled and unskilled workers from other states in India, especially from the north and northeast, looking for work. The government has given them the welcoming epithet “athidhi thozhilali” — guest worker — but they are routinely exploited by their bosses and treated with suspicion by the police and the public. By juxtaposing this issue with the seemingly unconnected story of the eradication of dangerous hornets in an ordinary suburban front yard, K. N. Prasanth addresses questions of power, displacement and belonging.

Prasanth told me that the story is based on two incidents from his life: the first a childhood memory of a nest of hornets — usually found in the forests of northern Kerala, called “poothappani” in the local dialect — being set alight, and the second an unfortunate road accident that led to an assault of two migrant workers by well-meaning locals. “That night, as I lay unable to sleep, the two men’s helpless faces begging for mercy filling my mind, I remembered the little creatures and their home set alight,” he said. “Both living, breathing beings of this earth that are trying to keep alive, fleeing from one place to another.”

What happens when we draw borders and boundaries based on our fears, perceived threats and notions of ownership? Prasanth’s story, in exploring this heavy question, is gentle and finely paced as it urges readers to consider the poignancy of survival. It is this narrative control even as he addresses urgent issues that makes K. N. Prasanth one of Malayalam’s most exciting contemporary writers.

It was an ordinary day until Divakaran came to Raghavan maash asking for permission to cut a piece of wood from the kanjiram tree to make a new handle for his hoe.

“Go right ahead, take whatever you need.”

As soon as the words were out of Raghavan maash’s mouth, Divakaran scrambled up the tree and disappeared into the canopy. Although he worked for Haridas doctor, the trustee of the colony’s residents association, Divakaran was helpful to everyone. Raghavan maash could not see him in the foliage, and when he heard the sound of the hatchet hitting wood he went back inside the house. Suddenly, an almighty roar shook the house and the trees, and by the time Raghavan maash rushed back out, Divakaran had dropped his hatchet and run away, screaming. A loud buzzing noise chased after him. Divakaran ran down the lane and jumped into the temple pond and lay submerged in the water. When he eventually came up for air, his face had swollen so much that he could not open his eyes. Climbing out of the waist-high water, he fell to the ground in a dead faint.

Divakaran, who had big eyes and strong muscles, lay in the hospital bed with a puffy face and swelling all over his body. When Raghavan maash went to see him, his relatives and friends showered him with abuse. They still called him “maash," as any man who was a teacher, retired or otherwise, would expect to be called, but that did not stop them from setting upon him and almost laying hands on him. They accused him of sending Divakaran knowingly up the tree that had a wild hornet nest in it. Haridas doctor was a shareholder at the hospital, and Divakaran had been working for him when he climbed the tree, and yet the relatives insisted that Raghavan maash pay the full 3,000 rupees for his treatment. He did, and then went back home with a mind aching like it had been stung by a hornet.

He had stopped writing poetry and reading a long time ago, but the trees gave him the solace his old poems once had.

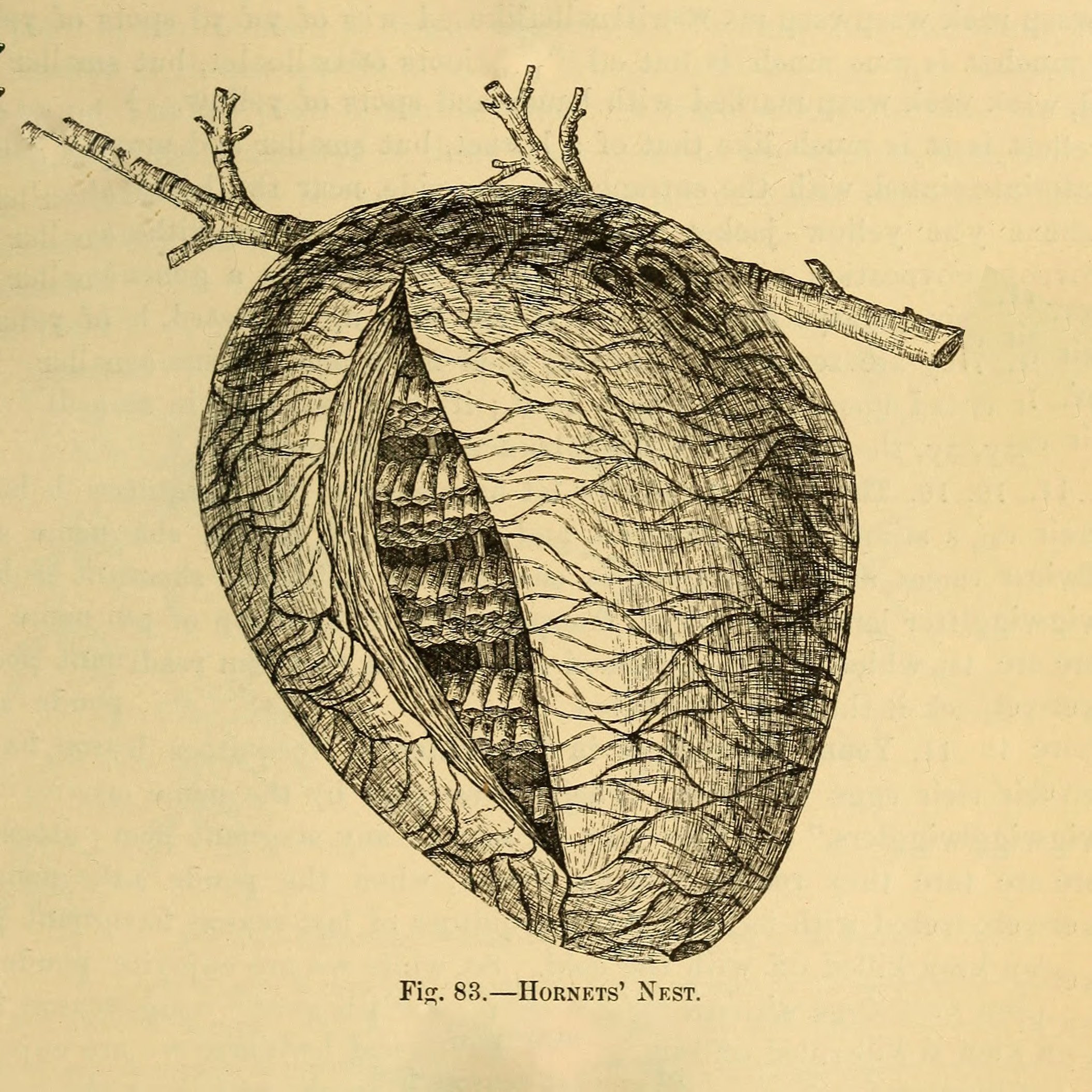

The hornet nest was hidden in the foliage of the kanjiram, which was part of the small grove around the house. Resembling a gray, slanting mud pot, the nest was visible only if one looked very carefully. When the wind blew, huge poisonous hornets, with yellow bands on their black bodies, flew in and out of the nest, humming. With a shudder, Raghavan maash recalled pelting stones at the njaval tree next to it to drop purple fruits for the neighborhood’s children.

He had planted the trees — now fully grown, with branches covering the whole property — when the house was being built all those years ago. When he had purchased the land, there was not a single tree on it. In those days, he used to write poems under the name “Raghavan Vattamthitta” and publish them himself, and it was a visit to a favorite poet of his that had seeded the idea of planting trees around his new house. But he could not emulate the poet and place stone benches among the trees. “What do you think this is? A railway station?” his wife, Sathi teacher, had asked, effectively putting an end to that idea.

By the time Raghavan maash retired from his teaching career, the trees had grown and filled the plot. He had stopped writing poetry and reading a long time ago, but the trees gave him the solace his old poems once had. When a marriage proposal for his daughter Athira came to nothing, Sathi teacher told him that she would not talk to him until the wilderness around the house had been cleared away. As soon as the prospective bridegroom’s family stepped through the door, the young man’s father looked around and remarked that even though it was right by the side of the road, no one would believe there was a house there. And the young man remained glum-faced even when he was introduced to Athira, and sat in front of the tea and snacks as if he were being forced to do so. Not half an hour passed after they left when Krishnan maash, who was the go-between, called. He was the headmaster at the school where Raghavan maash had worked.

“Let’s just forget about this match,” Krishnan maash said.

“Why? What’s the matter?” Raghavan maash was overcome with anxiety. Athira was not like him. She took after Sathi teacher, and she was well educated.

“Whatever it is, tell me,” he said in a stronger voice.

“Not right in the head, that lot,” Krishnan maash said, laughing. “Your house doesn’t have enough light, says the old man, and the forest around it makes it dark even in the daytime. It seems the boy needs a well-lit place.”

Raghavan maash was shocked. If Sathi teacher came to know of this, the trees would all be gone, cut right down to stumps. He remembered how she had come home and created a ruckus after she was made the butt of a joke in the staff room, her colleagues teasing her about how she managed to live in a forest.

But after the marriage proposal fizzled out, Athira told them about Hisham, her secret boyfriend. It took a while to convince Sathi teacher. When Hisham came to their home for the first time and remarked that a few benches among the trees would have been good, Raghavan maash raised his eyebrows at Athira as though to applaud her on her choice. Still, to his great confusion, Sathi teacher kept insisting that the trees should be cut down before the wedding to let in the light.

“Happy now?” she asked when Raghavan maash returned from the hospital. “All we need now is for the guests at the wedding to be stung by those hornets. That’ll fulfill your love of nature!”

She stomped off, leaving Raghavan maash in a quandary. Unable to think of what to do next, he called on his friend Krishnan maash.

“These are the poothappani variety of hornets. Vicious, they are,” Krishnan maash said. “A proper sting can kill a person. Don’t need anything more than the touch of a crow’s wing on the nest for these to be agitated. And if it happens in the nighttime, they will swarm to the faintest of light. In the olden days, when people went out at night in the light of a palm-leaf torch, they would have thought that these were poothams, spirits of the dark, that stung them. Maybe that’s why they’re called poothappani.”

The explanation made Raghavan maash angry and sad at the same time.

“Well, find me a solution,” he said, even as the sadness won and threatened to spout a spring of tears. Raghavan maash rarely did anything without consulting Krishnan maash, who, although he was younger, always found solutions to problems.

“Don’t you worry, Maash.” The answer came from Suresh, who drove Raghavan maash’s car. Raghavan maash could not drive and it was Suresh who took him everywhere. “They catch the tigers that wander out of the forest these days. These hornets are nothing!”

“Tell me, Suresh, how many hornets do you think there are in that nest?” Krishnan maash asked, smiling.

“A hundred, I’d say, maximum,” Suresh said, looking at them in the rearview mirror.

Krishnan maash laughed. “Well, it is estimated that there are well over 6,000 by the time a nest is finished,” he said.

A swarm of hornets buzzed inside Raghavan maash’s head. Surely Krishnan maash was making this up, just to scare them, he thought, feeling angry at his friend.

“Have you seen these things, Suresh?” Krishnan maash continued blithely. “Around 3 to 3 1/2 centimeters long, they are. Ten of them can take the life of a grown man. They’re rarely found outside of the forest. When something happens to their nest, they find another place to build a new one. May have been ousted from somewhere and they came to Maash’s property. Perhaps heard of his great love for nature!”

Their laughter was like a dagger to Raghavan maash’s heart.

The car stopped near a fallow field.

“We have to walk a bit from here.”

The field, at the end of May, was parched, the soil cracked. They walked along the earthen walkway toward an old house. A woman, old yet strong-looking, came from the back of the house as they approached.

“Ambuvettan?” Suresh asked in a deferential voice.

“Ey, someone is here for you,” she called into the house. Turning away from them, she tightened the mundu around her waist and went back to where she had come from.

The man who emerged from the darkness of the house looked familiar but Raghavan maash could not place him. Muscles lost of their definition hung loose on his arms and chest as though they were reminders of the past. He invited them onto the veranda and bade them to sit. Standing beside the bench that could barely seat three people, Suresh told him why they were there.

“Takes only a night’s work, fellows,” said Ambuvettan. “Some petrol, a good-sized torch made of coconut palm leaves and some cotton cloth.”

Stories rose as Ambuvettan agitated the hornet nest of his memories, of the untold number of poothappanis he had set fire to from the time he was a young man, of the dangers he had faced as well as the hilarious moments. Raghavan maash looked at Krishnan maash and Suresh as though wondering why they were sitting there and wasting time listening to the old man’s brags and banal jokes.

“But Ambuvettan, tell us what we should do. Maash’s daughter’s wedding is on the 28th. We’ve got to find a solution to this problem by then.”

Krishnan maash sounded as though he was ready to fall at the old man’s feet. Suresh wondered why he behaved like that sometimes even with him, begging and pleading, forgetting that he was the headmaster of the school and Suresh was only the peon.

“Takes only a night’s work, fellows,” said Ambuvettan. “Some petrol, a good-size torch made of coconut palm leaves and some cotton cloth. It’s absolutely important that there isn’t even a grain of light anywhere near because if there is, the moment we set to work, the hornets will swarm straight to it. So one person climbs the tree while others wait at the bottom, ready with stakes wrapped with petrol-soaked cotton. Now you’ll ask me: Why not light up the nest from the ground? Ah, that won’t do because by the time the stakes are raised to it, the hornets would have begun to swarm. You take the torch to the nest and light it from the top. It should be big enough, mind you, to set the whole nest on fire in a single blaze.”

Listening to his explanation, Raghavan maash began to feel better.

“But you’ve seen the state of me,” Ambuvettan continued. “Do you reckon I can climb trees and show off my heroism like I used to?”

He straightened his legs and Krishnan maash felt the bench on which they sat shudder.

“Tell you what. You find a couple of young guys. I’ll tell them what to do, and I’ll be at the bottom of the tree holding the torch.”

Promising to come back as soon as they found the right people for the job, they got up to leave. Suresh tried to hand him the money Raghavan maash had given him earlier.

“Haven’t done my job yet, have I?” Ambuvettan said in a rough voice. “Besides, I don’t take money for doing this job. Not a difficult job, mind, just needs a bit of courage. Human life is more valuable than a hornet’s, right? Hornets are trying to live too, making their nests. Humans have inside them envy and cruelty and pride and so on and hornets, well, they have a bit of poison. That’s all. They don’t know, do they, that they’ve built their nest in a tree on your property. Trees are all the same to them. Who owns the trees, in any case? They spend weeks building their home and when their babies start forming inside, we pick up a stone and strike it. And so they attack. Is there any creature in this world that does not attack when its babies are threatened? And when we burn down the nest in the night, we’re actually burning down an entire country with thousands of citizens!”

They got back home to find a few people — officials of the residents association — waiting for them, which set Raghavan maash’s heart beating faster. Already there were murmurings about his lack of interest in the activities of the association. Vijayan, a police officer who was the secretary of the association, stood with his arms folded across his chest, puffed up as though he had been stung by a hornet.

“Tell us, Maash, what exactly are you going to do about this?” The question, in a loud voice, was from Dileepan Nambiar, who owned the medical shop.

“It’s been four days since Divakaran was hospitalized, and you’re still making up your mind,” said Vijayan police.

He lived next door and had tried many times to pick fights. One issue was the leaves that fell into his yard from Raghavan maash’s trees. Refusing to be pulled into arguments, Raghavan maash got the branches that leaned into Vijayan police’s property pruned. Then Vijayan police filed a complaint at the municipality that mosquitoes were breeding in the terra cotta water dishes that Raghavan maash laid out for the birds. Raghavan maash solved the problem by turning the dishes upside down in the evenings.

Raghavan maash walked home feeling like a criminal. Sleep eluded him that night as he lay suffocating in the room with the windows shut against the hornets.

“We’re having a meeting this evening, at my house,” said Nambiar. He was the president of the association. “You must come. If you don’t, we’ll have to find other solutions.”

Just as they were leaving, walking in the shade of Raghavan maash’s trees, a scream emanated from Vijayan’s house.

“Papa, Mummy has been stung by a bee!”

Vijayan ran to his house. A hornet, separated from the horde, had got into the kitchen and stung his wife, and she had picked up a broom and beaten it to death.

As he took her to the hospital, Vijayan put his head out of the car window and shouted through gritted teeth, “I want this sorted today! If not …”

The rest of the party examined the dead hornet and marveled at its size. Vijayan’s son picked up a stick and poked at the poisonous dart, sharp as a needle, on its backside.

At the meeting of the residents association, Vijayan police created an almighty ruckus. The mood was to isolate the nature-crazed Raghavan maash. Banging on the table, Vijayan threatened police action if one more person was stung by hornets. Raghavan maash told them about Ambuvettan, but no one stepped up to help with the dangerous job. Everyone saved their own skin and left the task of finding the men to do the job to Vijayan police.

Raghavan maash walked home feeling like a criminal. Sleep eluded him that night as he lay suffocating with the windows shut against the hornets. Sathi teacher’s grumbling voice circled above his head like an insect, telling him how they could have slept comfortably if only he had heeded her and bought an air conditioner. When he finally managed to fall asleep, a dream in which hornets swarmed outside the windows, ready to drill through them, woke him up.

Despite searching far and wide, Suresh could not find anyone willing to do the job of setting fire to the hornet nest. Everyone had some excuse. The members of his WhatsApp group offered to find people if he would buy them alcohol, but Krishnan maash, who was a devoted Gandhian, scuppered this idea.

The next day, as Raghavan maash sat worried, his hand to his heavy head, someone rang the bell. He got up to find Vijayan police standing there with two men.

“Hindi folk, but don’t worry, they know Malayalam,” he said. “Came over here from somewhere in north India 10 or 12 years ago. They’ll do the job. Let’s be done with it tonight.”

Pulling Raghavan maash aside, he whispered in his ear, “That short one, he is from Jharkhand. We have our suspicions that he could be a Maoist. The other one — he says he is from Assam, but we know he is an intruder from Bangladesh. So keep your eyes on them.”

With that, Vijayan police went away in the jeep that was waiting for him.

As the two men stood around wondering what they were required to do, Raghavan maash took in their appearance. Their dirty clothes were ripped in places, and their faces had wounds and bruises as though they had been attacked. The shorter one had some dried blood at the tip of his nose. Wondering whether they had been beaten by the police, Raghavan maash went inside to get his phone to call Suresh and Krishnan maash.

He did not comprehend the danger that was waiting on the branch. There was a rumbling in his ears, memories of the stories his mother had told him.

Drinking the water Raghavan maash gave them, they asked him where the tree was. Before answering, he asked them what had happened to them, why they were bloodied. One of the men, Jabir Sheikh, was from Nellie in Assam, and the man from Jharkhand was named Bhupenlal Muchi. Sheikh began to weep as they told him about being waylaid and beaten by a group of men on their way to their new jobsite. Having no idea why they were being beaten, and overcome with fear and pain, they had wet themselves. The attackers took them to the police station, and it was there that they found out that those who had beaten them decided they were child snatchers. Thinking about their own children back home, they wiped away their tears silently.

“Do we look like child snatchers?” Muchi’s voice trembled when he asked the question.

Sheikh patted his shoulder, his own eyes brimming with tears. As Raghavan maash stood there looking at them, not knowing what to do, Suresh and Krishnan maash arrived.

“Ped climbing chalega?”

Not sure whether to laugh at Krishnan maash’s attempt at Hindi, they said, in unison, “Sure.”

The sun had set by the time Ambuvettan arrived. Suresh had gone to fetch him in the car, but Ambuvettan sent him back, saying he preferred to walk. In any case, they had to wait until it was dark. Anticipating rain, they prepared the torches wrapped with strips of cotton.

Darkness fell. Vijayan police arrived dressed in civilian clothes, hurled abuse at the two workers and then stood aside, ready to watch the show. All the neighboring houses were told to switch off their lights and keep their doors and windows securely locked. When the entire neighborhood was enveloped in darkness, under Ambuvettan’s directions, Sheikh took a petrol-soaked torch and began climbing the tree.

“Your friend is a foreigner,” Vijayan said, putting his arm around Muchi’s shoulder. “An intruder. Anti-national.”

Sheikh heard him as he climbed up the tree. He did not comprehend the danger that was waiting on the branch. There was a rumbling in his ears, memories of the stories his mother had told him. Of nights of fire that set the lanes alight, of lives fleeing even as the rain and wind from the Subarnarekha put the torches out. He pictured those who had crossed the river in the darkness, shivering in their wet clothes like hatchlings. It was their voices murmuring in his ears now. The land had not yet become two separate countries, but they were already on the run then, and they continued to run even after it was cleaved apart. A crazed, desperate fleeing that prevented them from settling down anywhere, as names were laid at their feet — intruder, anti-national, traitor — and they were threatened by hateful looks, police and prison. He sat on the branch, motionless, lost in the memory of ancient homes covered in a timeless darkness, lit only by the blazing flames. Was it the cries of those who were fleeing, with the meager possessions they could salvage as their huts burned down to ashes, that was ringing in his ears now? His head felt light. A cold wind announcing that the worst of the heat was about to be over shook the branches. Far away, lightning flashed behind clouds.

“Light the torch.”

Anger in Ambuvettan’s voice as he stood below, impatient for the flames and worried about the approaching rain. Snapping out of his thoughts, Sheikh flicked his cigarette lighter. But the blowing wind put it out. They could hear the approaching rain now and a rumbling that rose above it that could be the wakening hornets or the wind.

“Burn it, quick,” Ambuvettan called out again, anxious.

The flame shot up from the torch and set fire to the nest, and in the same moment the rain fell, huge drops accompanied by a roaring wind. As he stared helplessly at the dead torch, Sheikh became aware of a whole village fleeing above his head, shrieking.

Vijayan police tried to run, suddenly aware that the hornets, like a thousand arrows, were homing in on the moonlight of his phone, which had lit up with someone’s call. He tried to stuff it in his pocket, but they came at it, their collective drone filled with the sorrow and rage of those who had been ousted. The phone fell to the ground and continued to vibrate as though in symphony with Vijayan’s screams. The insects swarmed around its light as the rain quieted and withdrew to prepare for another deluge.

Vijayan police was rushed to the hospital in the jeep that had been waiting to take Jabir Sheikh and Bhupenlal Muchi back. He lay in it writhing in agony and continued to hurl abuse at them. Their bodies and minds were hurt and aching, but Sheikh and Muchi looked at each other and smiled as though they were savoring each horrible word that came out of his mouth. Raghavan maash watched them as his mind, cleared of its concerns, settled.

Lights came back on in the houses one by one as though they were shaking themselves awake. The rain roared once again as it passed over them, up above the canopy of the trees.

Published in the original Malayalam, “Poothappani,” in Pachakuthira, November 2019.

This story appears in K. N. Prasanth’s collection of short stories Pathiaraleela.

IMAGE: The Hornet’s Nest, 1887, via Wikimedia