Eleonor/Eleonora

“Was she out there somewhere, and what was she doing? And how had she survived the same ordeal as me?”

AUGUST 22, 2024

1.

About a year and a half before I saw Eleonora again in New York, Max and I were having breakfast at our hotel in Prague. We were in the middle of a European tour. He was the pianist and I his page-turner. Each of us was a gear that slotted into the other, he’d say, and in Prague this machinery would be no different.

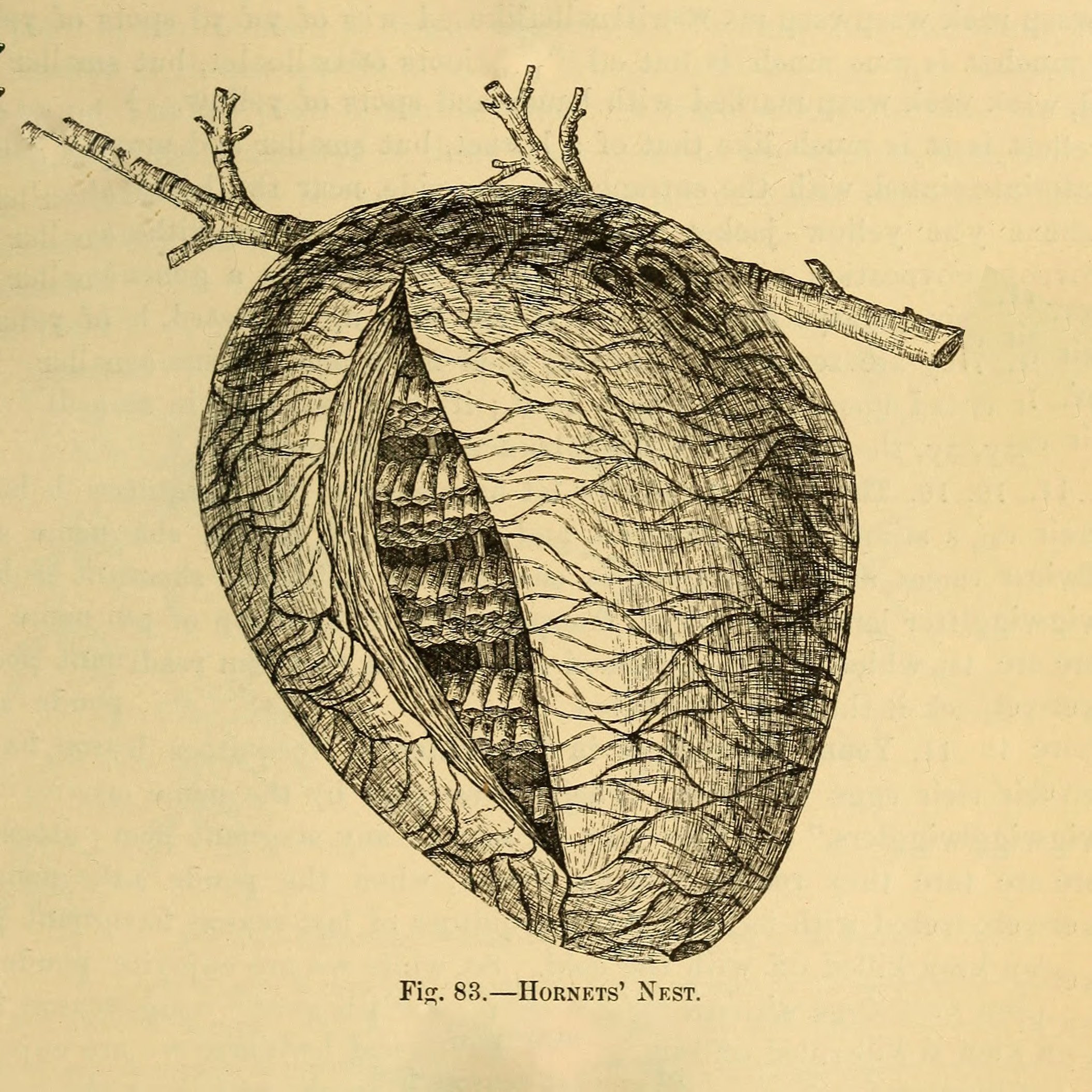

Without looking up from his newspaper, Max asked if I didn’t want to go out and explore the city a little. I’ll be practicing all day, but I wish I could go to the National Gallery, he said. They have one of Bronzino’s most important works.

Every time we wandered through the Frick Collection, Max always found a way to steer us past the portrait of Lodovico Capponi. As if caught up in love at first sight, he’d come to a halt before that dandy with the lofty gaze painted on an emerald-green backdrop. To me there was something slightly deformed about that painting from 1550. I honestly didn’t understand Max’s fascination with Bronzino.

Make the most of your time in Prague, he said. I need to go over the Chopin. You know what I was thinking for the encore, if there is one? Villa-Lobos.

Savage Poem.

It’s just so long and complicated.

You always say that.

One of these days I’ll fit that piece into a program — that’s probably better, right? It’ll be my little homage to you.

That would be lovely, Max.

Almost all the tables in the breakfast room were occupied by this point, and according to the large clock over the lobby doorway, it wasn’t even 8. Max leaned over to kiss me on both cheeks. He delivered each kiss with a measured delicacy, as if he were testing his own balance while leaving two marks on someone else’s face.

✺

I stayed in my room answering Max’s emails and forgot all about the painting. I only remembered to leave the hotel for a walk later in the afternoon.

Impossible, I thought. The copper-colored hair and gaze made languid by the whites of her eyes were identical to those of the person I’d met in São Paulo.

I strolled over to the plaza where the museum was, and from there someone pointed me down a curved, cobbled alley that would take me to its entrance.

I paid for my ticket and followed the cashier’s directions. That way, she pointed. There was a courtyard with an overgrown garden and statues. I crossed and started up a staircase on the other side. On a landing between floors I was surprised to find a door that seemed to be for “employees only.”

I decided to open it, and after moving through several empty rooms, I asked the only guard I could find where the painting was. He told me to turn left, and there I found not one but two Bronzinos: A portrait of Cosimo I on the left and beside it one of his wife, Eleanor, according to the captions.

Impossible, I thought. The copper-colored hair and the gaze made languid by the whites of her eyes were identical to those of the person I’d met in São Paulo. And the same name. Even the clothes, with their embroidery of pearls, suggested a certain rebellious spirit.

It was Max who told me later. That same gaze, showing the whites of the eyes between the iris and the lower eyelid, was something the Japanese called sanpaku. It was a sign that the person was destined to a tragic end, after a difficult life.

The longer I stared at the painting, the more I realized that my assimilation of the past had been a fantasy, or that things weren’t quite as resolved as I’d thought. My memory of our night out together began to surface and it troubled me.

Tears came, then muffled sobs, until I couldn’t help myself anymore. I bawled like a child and the museum guard came over to see what was the matter. He placed a hand on my shoulder, offering me some water and a few words in Czech.

As I clutched the plastic cup and made an effort to calm down, the man stood by my side, surprised, perhaps, by the effect of the painting. It was, after all, one of the museum’s highlights. He rested his hand on my shoulder again and I nodded. He turned and ambled away.

I was alone with Eleanor again. My attention drifted to the overlapping brushstrokes of the cobalt backdrop, a color that conjured a crepuscular noise, like that of an insect-filled sky. Gradually the blue of the painting became just blue again. It was thick, like the drying tears stiffening on my skin, and a tiredness slowly cemented my face in hers. Now Eleanor was serene, or appeared to be.

✺

I left the museum wondering why Max had insisted I see that portrait. It couldn’t just have been his love of mannerist painting.

The guard was nowhere to be seen as I took the broad staircase to the ground floor. I walked down the alley to the plaza filled with tourists. My thoughts were now on the concert and I felt like I was running late.

Max would take the stage a few steps ahead of me so that the applause and spotlight would fall only on him. Being invisible was part of my job, and I liked it. Safe in his shadow, I felt free. I would watch the great artist perform while waiting for signs from his body, discreet little commands to turn the pages.

✺

During the concert I turned two pages at once by accident. They were stuck together, and I wasn’t able to loosen them in time. Nobody noticed because Max went right on playing. It was a piece he knew so well that he didn’t even need me by his side, I concluded afterward. He’d once told me that all artists had their superstitions, and I was one of his. He kept me beside him so that everything would go well.

Nevertheless, at dinner I muttered an apology. I was so upset with myself that I didn’t know what to say. Nor did I want to accept that the mishap had something to do with the painting I’d seen hours earlier.

Max. I’m really sorry.

Max stared at me as if he didn’t know what I was talking about. He did that whenever he was annoyed, with cool aloofness. About what, dear? Cheers. He raised his glass.

I’m sorry. Max. You know why.

Why?

Never mind.

I’m all ears.

Why did you suggest I go to the museum?

Was it that out of the way?

No.

Because I thought it might be instructive for you.

Instructive how? To see mannerist paintings?

Didn’t you have a friend named Eleanor — Eleonora?

I didn’t think you remembered her name.

All right, so you went to the museum and didn’t like it. It happens. Now ask me something else.

OK … what were you doing all afternoon while I was at the museum? I tried calling your room and the concert hall to invite you along, in case you were tired of the piano.

Me? I tried practicing the piece, but I couldn’t.

You didn’t want to come with me to the museum.

Of course I did. But suddenly I wanted a different kind of distraction. I went to one of this city’s glorious saunas.

To get to know the boys of Prague better.

That’s right, sweetheart, he said, taking up my hand to kiss it. Next he filled our flutes with more champagne. I want you with me all the time, on all my trips. What happened happens. Pages stick together. But just out of curiosity: What do you think of that Czech exec?

The thin man sitting in front of Max was wearing a black silk shirt and twirling his glass clockwise. Before pressing it to his lips, he ran a finger across the arabesques on the surface of the Bohemian crystal and gave me a sharp smile.

Max’s longtime boyfriend, Scott, was afraid of flying and usually stayed in New York, which made Max’s life and his escapades with other men easier. Even so, he felt the need to explain himself, with a toast or a quixotic kiss on my hand. He sighed. Despite my slipup during the concert, Max had performed well and was in high spirits.

✺

I asked Max if he wanted to get some fresh air after dinner. It was still hot in September, and to him, fresh air meant a walk. Avoiding the gaps in the cobbled footpath, I tried to explain that I didn’t know what to make of my memories, of the fact that so many of them still revolved around Eleonora.

I told him everything in detail, starting with the hotel driver who had taken me to the museum plaza.

Before I finished my story, Max asked if the painting had really disturbed me.

It was terrifying, I said.

Which brought me to the inevitable. Was she out there somewhere, and what was she doing? And how had she survived the same ordeal as me? At this point Eleonora was almost a mirror image of me. Whatever that means. I kept looking at Max.

That night I asked if I could sleep in his room and he laughed. He said no way because he snored a lot and he’d be worse than usual because he’d forgotten his sleep apnea device.

It must have been about 6 in the morning when the phone in my room rang. It was Max, inviting me for a coffee on his balcony. I took a quick shower, pulled on a tracksuit and climbed the two flights to his room.

Max was shaving when I came in. We didn’t usually share this kind of intimacy, me sitting on his bed with my wet hair, but I poured myself a cup of coffee while he finished drawing the white foam from his ear to his chin. He made orderly lines, like a lawnmower, dragging the sleepy razor slowly around his chin.

He said pastries would be there soon and asked if I’d slept well. I leaned my head on my hand, said yes and watched him. Max told me we’d been invited to watch the final match in a tennis tournament — the Laver Cup. I asked if the invitation had come from the Czech exec. The poster boy for Bohemian crystal.

Max laughed. Yes, from that svelte, princely exec on the far side of the table.

✺

After Prague I barely slept for two weeks. I realized that Eleonora had never ceased to cast a shadow over my life. She bubbled up from the past like spring water, and Bronzino’s controlled brushstrokes had only intensified that impression.

Before Prague, I had gone more than five years without obsessing over the image of the rosy-cheeked redhead, my boyfriend’s neighbor, standing at the gate late that afternoon. I thought about Eleonora whenever I came across some random news about her on the internet, but I did so with a measure of detachment, until I came face-to-face with the portrait in Prague. I wanted the painting to correspond to something completely resolved in my life, but what came over me was the raw and pulsing memory of the Eleonora of years past, and it began to haunt me.

I felt an urge to place one image over the other, as if they were two transparent slides of human anatomy. I needed this connection between Eleanor and Eleonora so that I could keep moving forward.

✺

One day, on Long Island, I was watching the waves crash hard against the sand and listening to the music of the water, observing how the sea never repeated a movement. The water washed across the sand in layers, like two hands caressing each other, overlapping only partially.

I didn’t know how to explain Eleonora’s reappearance in my life, but something had been set off inside me. I thought about sending her the postcard I had bought for her in the museum. I worried about who might read it, but the gesture would be more concrete than an email, so I put the card in an envelope and asked Max if I could use his address for the sender.

2.

The blue of the dawn threatened to shatter the glass doors, so uniform and dense was the beam of light striking them from outside. Soon the sun would crystallize the surface of the brown snow outside the arrivals hall, where the pedestrian traffic was concentrated, and then the white gleam would slowly return to Queens.

No one who had followed the story of our night of crime and years of punishment — a case that had resounded across Brazil — would have forgotten the picture of me, and then, the next version of it, with the black bar over my eyes.

I glanced again at the flight monitor, as I’d been doing since 6 o’clock that morning. Landed. I celebrated by shifting my weight from one leg to the other, then resumed my position leaning on the metal bar, a space that was now difficult to hold on to because of the collective enthusiasm for the flight’s arrival. A dozen almost identical drivers in black jackets held placards with their clients’ names at chest level, on the lookout for a corresponding face.

One passenger, talking on a phone clamped between his chin and his shoulder as he untied a sweater from around his waist, stared at me, caught in murky but unavoidable recognition. He was speaking Portuguese, so I assumed he’d been on the flight from São Paulo. He bent over and switched hands to pull his suitcase. As he passed me, I watched the other passengers with a thumping heart. I looked back at the taxi stand and massaged my hands to free my mind of doubts. The stiffness in my joints made them feel tighter, a tangle on the inside.

Eleonora’s trip had no doubt made the news. I figured someone must have recognized her at the airport in São Paulo. I pulled out my phone to search the internet and, with my head bowed over the screen, took refuge behind the curtain of hair that flopped down from behind my ears.

No one who had followed the story of our night of crime and years of punishment — a case that had resounded across Brazil — would have forgotten the picture of me, and then the next version of it, with the black bar over my eyes. The effort to protect the privacy of a minor had been useless, as the defense had arrived too late, well after the original photo had already done the rounds on social media. In the photo without the black bar, my blue eyes were smiling before the night out, staring straight at the camera. Beside me were Eleonora and my boyfriend, Matias. It was the only photo of the three of us together.

After doing time at Fundação CASA, a juvenile detention center, I had moved to New York, just over six years ago — something else that shouldn’t have been publicized, but when people want something, they’ll sniff it out. Leaving the country had made me even less civic in the eyes of my countrymen; it was another sign of my arrogant, even discriminatory attitude, a lack of gratitude for the place that had supposedly reformed me.

The stream of passengers increased, and for a moment I thought she’d slipped past me.

✺

Ana, it’s me. The red hair and the soft brown spray of freckles confirmed what she said, as her eyes narrowed in a cheeky smile that was lifted by a slightly raised chin, insinuating natural determination. You came to meet me. That’s so nice of you. Thanks.

It’s the least I could do, Eleonora, I said, smiling back, trying to hide how strange it felt to be saying her name. Need help with your suitcase?

Eleonora glanced at the people around her and smiled again. No, I’ve got it. I can’t believe I’m here. Give me a hug.

I recalled my trip to Prague a year and a half earlier, a journey that had brought me back to her after discovering that portrait of the other woman.

I’d stood before that painting for hours. They didn’t just share a name. Eleanor of Toledo looked exactly like her. A chill ran through my entire body, and I took a step back to get a good look at her. The whites of her eyes were pronounced and gave her a serious air, and when she stopped smiling her lips remained parted as though she needed air. That wasn’t something I remembered.

✺

As we exited through the sliding glass doors, we felt the heat of the vestibule, followed by a dramatic drop in temperature outside.

Fuck.

I know. December is like this.

The day was dry, the sun not fully risen. Eleonora’s teeth would start to ache from the cold if she didn’t close her mouth. I rotated my wrists and stretched my fingers, feeling her pain. Ahead of us, pedestrians in hoodies and coats stared impatiently at the passing traffic, darting between cars to cross over. I pointed to the queue at the taxi stand but Eleonora looked over my shoulder. I turned quickly to follow her gaze.

I had left Brazil and gone into exile precisely so I wouldn’t be recognized in the street but, secretly, I envied her notoriety.

The feeling that someone was following me had begun the day after the crime. Although it had faded somewhat during my time in detention, it had become a constant sensation once I was out, no matter where I was. I turned around. Two men I recognized from the arrivals hall were walking quickly in our direction, alongside a woman pushing a man in a wheelchair, wrapped in a scarf and stiff with cold.

What is it, Ana? Relax, she said in a hushed voice, arching her eyebrows. We call attention to ourselves no matter what we do — at least we think we do.

I was embarrassed that Eleonora had read me so easily. She knew exactly how I felt, not least because she was accustomed to it herself.

Because she wasn’t a minor at the time, her sentence had been much longer than mine, and even in prison everything she did made the news. I had left Brazil and gone into exile precisely so I wouldn’t be recognized in the street, but secretly, I envied her notoriety.

✺

Eleonora fell asleep in the car. We’d spoken on the phone a few times in the days preceding her flight. I recalled her mother’s reaction upon learning that she’d bought a ticket to the United States. Why dredge it all up again? It’s more than proven that that Ana girl’s a psychopath. Now Eleanora’s mother could threaten her from afar, but it’d be no use, not even to feed her own vanity.

Eleonora had told me that she had justified the trip by explaining how she just had to see me again. During our last phone call, she had tried to muffle the yelling in the background, telling her mother to leave her alone. In public, Isabel had appeared to take Eleonora’s defense, entering the fray to defend her, taking on public and press alike. In private, things were different. Selfish! I heard her scream.

The only time I’d seen Isabel was at the sentencing. She was a redhead like Eleonora and had an air of moral superiority about her. I remember her studied, cautious voice. Her speech was almost flat, showing vulnerability but also an understanding of her daughter’s misadventure. You could see she was a relentless tiger somewhat subdued by tranquilizers — a strange, suffocating person I couldn’t imagine living with. Some said that Eleonora had left one cage for another.

✺

The driver looked in the rearview mirror and asked if it was the right place. I nodded. As we got out of the car in front of my building, three people came toward us carrying a camera and a microphone.

I remembered the note that someone had left with the doorman the night before. It was from a reporter at a Latin American TV channel. She wanted to do an interview.

It was obvious that the press wasn’t going to miss a nice round figure like a 10-year anniversary, I realized as I watched Eleonora wheeling her suitcase — especially not one involving a reunion in another hemisphere. That’s what Latin American TV channels were for, I tried to joke to Eleonora, but the reporter was practically on top of me. Who else could have left the note? It could only have been her.

I’m sorry, was it you who left a note here last night about an interview?

Just one little question, she went on without listening.

Practically inside the building by now, Eleonora stepped back out. No little question, she said, pushing the camera aside.

In her effort to protect her colleague, the reporter lost her balance and fell.

What did I tell you? Listen here, this ain’t your turf, lady. It’s her home. And nobody in the building wants this crap. So fuck off. And you can tell everyone I didn’t give you the fucking time of day. We didn’t.

He no doubt knew all about her, Brazil’s penitentiary queen who’d just flown to New York to visit her accomplice in murder.

Still on the ground, the reporter listened, dumbstruck. The doorman didn’t know whether to stop Eleonora from entering the building, defend us or help with the bags.

Curious bystanders began to gather on the Central Park side of the street.

I placed my hand on the reporter’s shoulder in a gesture of goodwill and she gave up trying to smooth a loose strand of hair back into her bun. It was nothing, I said, and the doorman saw everything. You fell because you lost your balance. Would you like a glass of water?

No, thanks.

Excuse my friend. She’s tired and you should respect that. Coming here with that light on, shoving the mic in our faces — it’s unnerving. Do you understand?

Still breathing heavily, Eleonora said the reporter was blackmailing us and the situation was ridiculous. We didn’t invite you here, she went on, we didn’t agree to do an interview with your crew. It’s freezing, Ana. Who are these people? I didn’t know we were so interesting.

Take it easy, Eleonora, I said, trying to control my nerves.

The reporter stared down at her feet. The last thing I want is to make a scene, she said. She turned to me. When you have a moment, give me an interview? Here’s my card. Thanks, she added, straightening her hair, insinuating that she was only doing her job.

You’re welcome, Eleonora replied. Bye-bye, she said, yawning.

On behalf of us both, I shook the reporter’s stony hand to show that we were civilized and left it at that.

Eleonora threw her hands up in impatience.

✺

In the elevator, Eleonora examined the doorman while I tried to hide my curiosity about her. The thin lashes extending over her rosy eyelids contrasted with the extraordinary flash of her eyes, which were growing irritated from not blinking.

She wanted to pressure us into an interview, she blurted out.

Diego, this is my friend Eleonora. She just got here.

No me diga.

I stared at his shoes, then his white gloves. His skin struck me as floury, and his eyes opaque, like old breakable marzipan, reminding me of the eternal cramp that made him shake his leg every so often.

He forced a smile for Eleonora. Como le fue de viaje?

He no doubt knew all about her, Brazil’s penitentiary queen who’d just flown to New York to visit her accomplice in murder.

Muy bien. Gracias, Diego. She winked at him as we got off on the fifth floor. I just no hablo español.

✺

From the window we could see that the crowd had dispersed. One man remained, and although I couldn’t recall ever having seen him before, his gaze drifted up, as if he had been watching a plastic bag carried by the wind and had lost sight of it. Suddenly he was looking right at me, or I thought he was.

He looked like he wanted to say something. Confused, I realized that my fingers still hurt, as they had at the airport. I took off my gloves to massage each tendon, each bone. What stung in the winter went numb in warmer weather.

I just don’t think that reporter and cameraman should’ve come to bother us, that’s all. Eleonora stretched her legs over the arm of the sofa. What’s crazy is that everybody saw what a pain in the ass that woman was being.

I agree, but let it go.

Are you pissed off?

Me? I turned to face Eleonora, unsure if I should say anything else. No, I’m not. I just don’t want a scandal.

She laughed. I’ll behave myself. But seriously. I can’t stomach people who think they can get in your face like that just because you’re in the public eye.

Sometimes you have to express your discomfort and impatience, I know. But I’ve spent the last six years of my life here in the U.S. staying out of trouble. That’s all.

Seeing Eleonora stretched out on the sofa like that, I began to wonder what I’d hoped to achieve with her visit. We’d spoken a few times, but she was still a stranger. I could taste blood in my mouth. I ran my tongue over my teeth, which I’d flossed vigorously as soon as I woke up. I could no longer remember if I’d insisted that she come, or if she was the one who had really wanted to come.

This text, excerpted from Thaw, was translated from Portuguese by the author but also owes its final form to the essential input of translators Alison Entrekin, Sophie Lewis and Nina Perrotta.