Crimes of Starvation

In conflicts around the world, food and hunger are used as tools of war. What's the role of international law in addressing human-inflicted starvation?

MAY 15, 2024

State of the World features occasional dispatches on the latest news, events, and ideas. To receive these updates directly in your inbox, sign up for our newsletter.

✺

This week, Sarah Nouwen talks with Alex de Waal and Michael Fakhri. This is an edited transcript of “Episode 26: Hunger for Thought” originally recorded on the EJIL: Talk! podcast.

Palestinians line up for food during the ongoing Israeli air and ground offensive on the Gaza Strip in Rafah, Jan. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Hatem Ali, File)

After seven decades of a decline in mass death from starvation, starvation is now a reality for millions of people, and this starvation is overwhelmingly not due to natural disasters. Médecins Sans Frontières has reported that in a camp for displaced people in North Darfur, at least one child is dying every two hours from starvation. According to research published by the Clingendael Institute, Sudan as a whole is facing the worst hunger level ever recorded during its October-to-February harvest season, forecasting that around 7 million people could face catastrophic hunger by June 2024, with mass starvation in prospect.

According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, or IPC, the entire population of the Gaza Strip, about 2.2 million people, is facing a situation of food crisis or worse, with half of those people facing catastrophic hunger. This is the highest share of people facing high levels of acute food insecurity that the IPC initiative has ever classified for any given area. Famine is imminent. In Haiti, the same IPC found that nearly 277,000 children aged 6 to 59 months are facing or expected to face acute malnutrition. We can continue with dramatic figures from Ethiopia, Somalia, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chad, Syria — and the list goes on. Hundreds of millions of people are hungry.

What rights, crimes, venues and remedies does international law offer to challenge or counter starvation? Could it also be complicit in generating hunger? How?

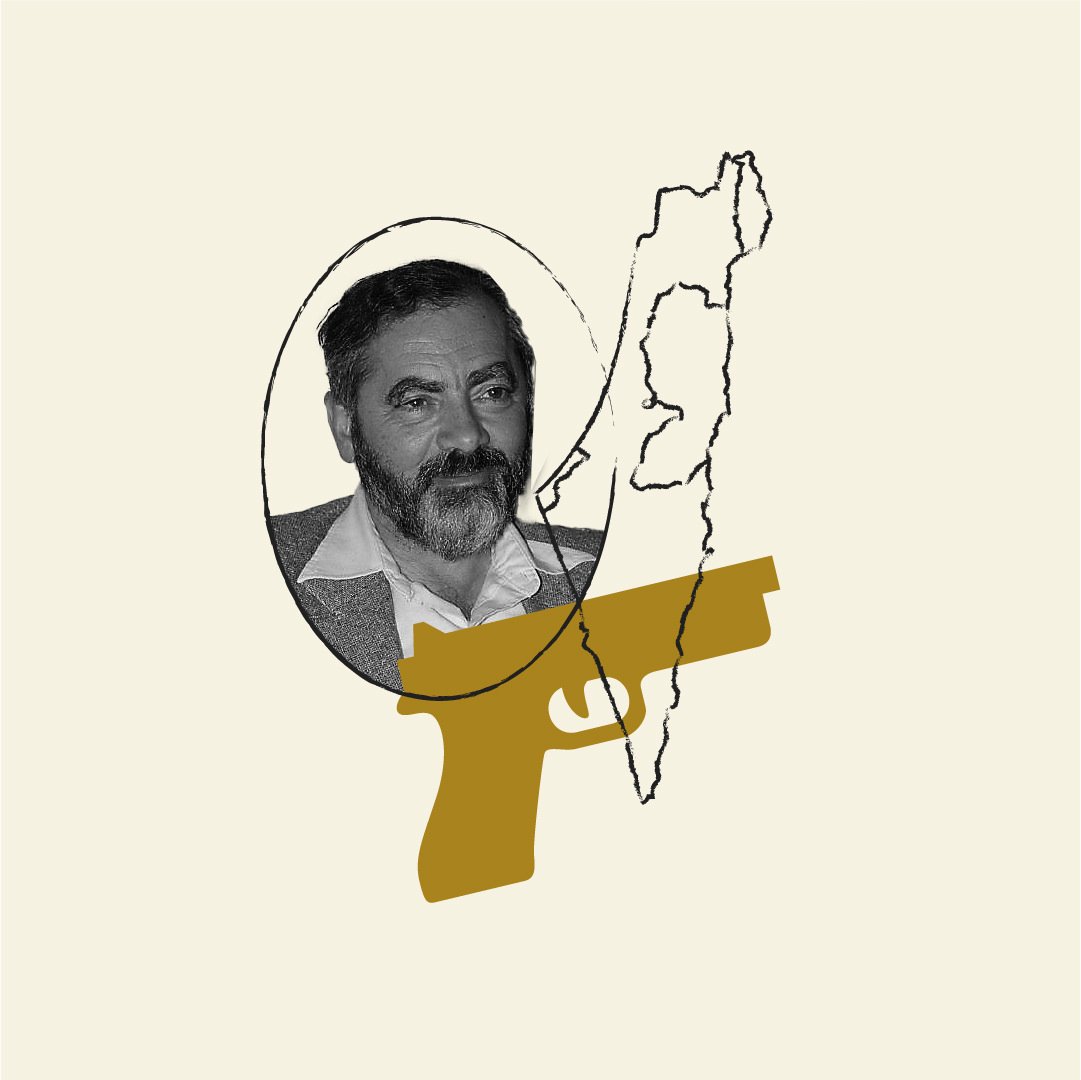

Alex de Waal is the executive director of the World Peace Foundation and has campaigned against starvation, also advocating for a more active role for international law. Michael Fakhri, as the UN's special rapporteur on the right to food, has tirelessly rung alarm bells about hunger in dozens of places across the world, not shying away from speaking painful truths to power.

As de Waal has sharply observed, the verb “to starve” is also transitive. It is what people can do to each other, like murder or torture. Fakhri has told the Human Rights Council that he is seeing food being used more and more as a tool of war. Children are the people who suffer the most.

— SARAH NOUWEN

SARAH NOUWEN: Let’s talk about public international law generally, or specifically the Genocide Convention, where the International Court of Justice has thought and grappled with the problem of hunger and famine recently. It issued its provisional measures in the case that South Africa brought against Israel.

Recently, on March 28, the court amended its provisional measures in light of the further deterioration of the catastrophic living conditions of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. It ordered Israel to take all necessary and effective measures to ensure — and this word, I think, is a crucial change from the earlier order — without delay, in full cooperation with the United Nations, the unhindered provision at scale by all concerned of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance, including food, water, electricity, fuel, shelter, clothing, hygiene and sanitation requirements, as well as medical supplies and medical care to Palestinians throughout Gaza, including by increasing the capacity and number of land crossing points and maintaining them open for as long as necessary.

It also ordered Israel to ensure with immediate effect that its military does not commit acts which constitute a violation of any of the rights of the Palestinians in Gaza as a protected group under the Genocide Convention, including by preventing, through any action, the delivery of urgently needed humanitarian assistance. Now, was this amendment enough?

ALEX DE WAAL: Well, I think it’s quite dramatic and significant in several respects. First of all, the fact that the court considers the imminence of what the IPC considers famine a sufficiently important change in material circumstances to issue a new instruction. Secondly, the fact that part of the order was unanimously passed, even with the support of Israel’s own judge on the ICJ, Judge Aharon Barak, and the other part by 15-to-1, so an overwhelming majority.

The biological effects of starvation last a lifetime and indeed into the next generation, but famine is also a social trauma.

Also because it uses the word “effective,” so it implies that not only must Israel act, but the act must actually be effective in preventing the descent into famine. I think it may be somewhat controversial to imply from that that failing to do so would be a failure to adhere to the Genocide Convention, i.e., that Israel is on the brink of, if not already, committing genocide by starvation.

SN: This is also what several of the separate opinions of the judges who were of this view pointed out, but it didn’t make it into the majority decision.

AW: The biological effects of starvation last a lifetime and indeed into the next generation, but famine is also a social trauma. The indignity, the shame, the rifts in the social fabric are ones that are deeply embedded in people’s memories, and they cause a trauma that can last for generations. In fact, even today, in Ireland, in Ukraine, in different parts of the world, people struggle to memorialize, to commemorate famines of generations ago.

MICHAEL FAKHRI: It’s interesting that the court isn’t using clear enough language. It implied. So one can interpret the majority decision as suggesting that cease-fire is a necessary precondition to allow for humanitarian relief to enter, with a prioritization of entering on land. They recognized a lot of things in their decision, but the actual judgment was ambiguous enough that six judges felt it required even clearer language, that they felt they had to add more clarity, more direct language, to avoid any exploitation of ambiguity to actually … I don’t know if we can say prevent famine, stop famine, at this stage.

What’s also interesting to me is that they did use the language of starvation, but it was a passive sentence. There was no indication of who is starving the Palestinian people in Gaza — probably because the ICJ doesn’t necessarily have jurisdiction on starvation as such. What they’re talking about is the Genocide Convention, of course, so I’m still thinking through that. But to build upon Alex’s point, Israel seizing military operations is a precondition. We’re going to see the effects of the starvation campaign in Gaza for generations to come. So we should also be thinking not just in terms of reconstruction and rehabilitation, but reparations. Who is responsible, then, to ensure that the Palestinian people in Gaza can continue to live with dignity when this war finally ends?

SN: We see and hear the Genocide Convention, international humanitarian law, human rights law and the right to food being invoked in the context of Gaza. But in the context of Sudan, Yemen, Congo, Haiti, we see far less usage of international law — in coverage but also of course in terms of legal actions to get food to people. Is this observation right?

MF: Let’s start with Gaza and then turn to the others. As the secretary general said, all of this did not happen in a vacuum, but then it creates a debate. What’s the correct context? We can start with this: The dispossession of Palestinian people from their land in the mid-1940s was a central issue of the United Nations and international law, and has remained as such. So this war enters into a situation already filled to the brim with every element of international law one can imagine. And the Palestinian people have used international law as a form of resistance for over 70 years.

This is a continuation of using international law as a strategy both to oppress and to resist. It’s not by chance that some of the leading public international lawyers in the world are Palestinian. That’s out of necessity.

To turn to the other conflicts, I think international law is there, but not at the foreground, and not being used in strategic terms by the parties. I think international law is there to understand the conditions that were created that led to those particular conflicts, starting again from how countries were created, how power was distributed and redistributed and the like.

Maybe the distinction is that international law is being used very tactically by all parties, and has been for a long time, in Gaza, and maybe it’s more in the background in creating the conditions in the other conflicts.

SN: How useful has law been to address the current disastrous food situation in Sudan, and could it be otherwise?

AW: Well, building on what Michael said, it really hasn’t been used, and I think we can look at several reasons for this. The first is a continuing, powerful tendency to naturalize starvation, particularly in the African context — to assume as the routine explanation that if Africans are hungry, it’s because they are maybe improvident people living in a harsh climate. Even when this is very clearly not the case, this tendency to blame the weather or, more recently, blame climate change comes to the fore.

A second factor here is that when one is dealing with getting humanitarian access in a complicated war in which there are no good guys and bad guys — such as Sudan today or indeed Sudan in the past, in the civil wars of the 1980s, the 1990s, the war in Darfur in the 2000s — you are faced as a humanitarian actor with conflicting demands. On the one hand, you want to feed the hungry, and you want actually to give material assistance to those who are under the authority, the control of a military or political actor who can deny access. If you start calling out that actor for culpability for starvation crimes, your access may be jeopardized.

This dilemma has been with us for decades, and on the whole, the way in which this dilemma is resolved is in favor of: We will remain silent about the crimes, including any crimes that may be committed, sexual and gender-based violence, massacre, forced displacement, or at least we’ll deal with them only in a very generalized or abstract way, in order that we can have access. Now, there was pressure to overcome this problem in recent years because it was so persistent, which led to the UN Security Council adopting a resolution on armed conflict and hunger, Resolution 2417, which was six years ago.

Part of the rationale for this was that the responsibility for addressing that question of culpability when conflict leads to food insecurity would go up to a higher level, not to the operational agencies. But one of the things that subsequently happened was that the African Union didn’t take this on board. When the African Union came to discuss — through its Peace and Security Council, rather belatedly, four years later — armed conflict and hunger, it made no reference to either Resolution 2417 or to the fact that starvation very often is a crime.

It shouldn’t just be a matter of international criminal law. It shouldn’t just be just a matter of international human rights law.

It essentially equated the types of abuses that belligerents may commit in an African context with efforts by the United States and Western donors to impose sanctions and conditionalities and therefore tried to escape from really addressing this issue head-on. Personally, I thought this was a shocking abdication of responsibility and a regress from the norms and principles that had been adopted when the African Union was founded 20 years prior, which had a very explicit commitment to principles of human rights and international law.

So I think what we see in conflicts such as Sudan is that the entry points for using the tools that we have — international humanitarian law, international criminal law, and at the UN Security Council level — have essentially been abandoned by those who ought to be invoking them.

SN: In terms of outcome, do you think it would help the Sudanese people if there was an ICJ decision with provisional measures?

AW: I think it would play a very important role in raising the moral bar. It may not be that the law itself would be respected or enforceable, but the key point here is the toxicity of starvation crimes, and signaling to those who are perpetrating them just how abhorrent what they are doing actually is.

MF: There’s this real, almost dark, cynical aspect to international law that is revealed in your question, which is if you’re starving people indiscriminately, it makes it harder to make a genocide argument almost. How awful that is, how ridiculous our system is that that’s actually a dynamic that we have.

Something I’m doing in my forthcoming report that I’ll be presenting to the General Assembly is rethinking, then, the understanding and definition of starvation. It shouldn’t just be a matter of international criminal law. It shouldn’t just be just a matter of international human rights law. It is, I would argue — and will be arguing to the General Assembly in October — a fundamental violation of international law. Why is this not a jus cogens issue? Starvation is such a terrible, cruel, vile way of harming people that echoes into the future for generations that it should be at the core aspect a fundamental violation of international law writ large.

SN: When we say it’s a fundamental violation of international law, what are the types of accountability that we may want to be pursuing? What are the most useful forms, or perhaps the most justified forms, of accountability for starvation?

AW: I think the history of famine and the prevention of famine is very instructive here. During the colonial period, all the imperial powers were relentless perpetrators of mass starvation. One of the most telling and significant examples was the famine in Bengal in India in 1943, which came about through a number of factors, paramount amongst which was the policy of the wartime cabinet headed by Prime Minister Winston Churchill in London. This was an issue on which Indian civil society and the Indian Congress Party mobilized politically.

As a result, there was what I one time described as an anti-famine political contract in post-independence India, which meant that any Indian government that presided over an episode of food emergency or famine was punished in the press, by civil society and electorally. There was an awareness that this would happen. As a result — and Amartya Sen wrote very eloquently about this — the respect for civil and political rights in post-independence India translated into a very effective famine prevention system. So it is this politicization of the issue of famine — in the Indian case, within a national political system — that was the key.

One of the things that has happened subsequently, and particularly in Africa, is the diffusion of responsibility for stepping in to stop food emergencies degenerating into famine. With that diffusion of responsibility, with the international community playing an important role, it gives a pretext. It gives an opportunity for every actor to evade responsibility by blaming somebody else. So we need, I think, to somehow bring back that focus of popular public mobilization and outrage such that it may be a shared responsibility, but it’s a shared responsibility in which no one can blame the other — everyone must pay a political price for when starvation happens.

MF: Yeah, and I’ll add that there’s a continuation from that colonial history into sort of, if one can say, the post-colonial moment, even though colonization continues today. To continue in the subcontinent, then you have the famine in Bangladesh in the early 1970s. One of the causes of that was the Cold War politics of the time, which had the US denying trade to Bangladesh, punishing them for trading with the Soviet Union. At the time, during that same era, not necessarily connected directly to Bangladesh, but the head of the USDA at the time in the United States essentially said, “Food is a tool, is a weapon that we use.” This is in the 1970s. This is in living memory. Food continues to be used by all powers. There’s no good guys and bad guys here.

All countries have thought about using food as a tool of power to control, and sometimes it is used in a way that leads to starvation. But from the get-go, it’s always been used in this tactical way. There’s an interesting disconnection between the right-to-food community of activists and experts and the starvation community of activists, experts and actors.

It’s interesting to me that before the war in Ukraine, the World Food Programme used to purchase approximately 30 percent of its wheat from Ukraine. When Russia most recently expanded its invasion and occupation of Ukraine, it destabilized the food system because so many countries depended on the importation of wheat and fertilizer from Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. One of the charges against Russia is, “Ah, you’re making the already-existing food crisis that was triggered in 2020 worse.” Sure, true.

However, what the World Food Programme has done since the war began is increase its dependency on purchasing wheat from Ukraine while the war is ongoing, instead of turning to other sources of wheat like Canada or wherever that might be more politically stable right now, in an effort to support Ukraine’s war and resistance against Russian occupation. So the World Food Programme is making our food system more precarious as a result. It’s making its procurement problematic. It’s buying from a war zone in this political way.

We have to look at all the actors. Then there’s the issue of holding people accountable — this is where human rights is helpful. This comes from movements, from social movements, from communities, from the people affected directly. They can push — and using all tactics available, whatever they may be.

AW: The two communities of food activists have really been working in parallel and not properly communicating with one another. Those in the food sovereignty movement, who are challenging the agro-industrial corporations and their dominance of the world food system, have not really identified with those working in the humanitarian sector. I think part of the reason is that the global humanitarian sector is, as Michael just said, so dominated by the United States and Western Europe and therefore has been compromised by their political agendas.

The Ukraine case is a striking example, but other examples, if we go back in recent history, are the readiness of Western governments to use force in what we might call philanthropic imperial adventures — going back to Somalia in 1992, an occasion which cost me my job at Human Rights Watch because I objected to it and then had to resign in principle, but more recently in a slightly different context in Libya. What this has done is the humanitarian agenda has no longer become owned and championed across the Global South.

I think what we are seeing at the moment with the Gaza situation — and the challenge to Israel and indeed to Israel’s backers, especially the United States, by South Africa — is it is bringing these constituencies together to see: OK, we have a common purpose, a common agenda to challenge not only the political but also the corporate power that is behind our desperately dysfunctional global food system in both its political economy but also its weaponized political aspects.

SN: You’re both not merely leading thinkers but also activists in the fight against hunger. What would you recommend all of us who read the stories and see the images of people starving — what would you recommend us to do? What is meaningful political action? Should we also put our money where our mouth is and transfer money?

But if so, to which organizations? Recently, the press reported that a lot of organizations that are trying to get people out of Gaza are actually human traffickers and that banks should no longer work with them. It’s pretty complicated for people who want to help concretely. What can they do?

AW: The most important thing is public clamor, to make it so morally abhorrent to perpetrate or tolerate starvation crimes. I think that is really the number one thing. Second is that people should educate themselves about how this grossly dysfunctional world food system is operating and producing all these terrible outcomes across the board, including in our own bodies. Third, yes, money is needed immediately. Here we have a real dilemma because the existing world humanitarian system with the World Food Programme and other UN agencies and other international agencies, mainly funded by the United States and Western Europe, is not great, but it’s the only one that we have.

It’s at the moment facing very serious budget cuts. The World Food Programme’s budget is down more than 30 percent. Its staffs are being cut, etc. While it’s not ideal, it’s what we have, so it does need to be funded for now, even while we try and create a better system.

MF: I totally agree in terms of speaking out, educating oneself, putting political pressure. Do it everywhere.