The Remains of Uruguay’s Dictatorship

The military’s pact of silence is slowing down investigations to find the missing.

JANUARY 16, 2025

On a frigid day in late July 2024, relatives and reporters crowded around a sunken pit of black earth in a military zone in Canelones, Uruguay, about a dozen miles north of the capital, Montevideo. They peered down into the hole and wondered if the skeleton at its bottom could be their brother, their father, their uncle.

Nearly two months later, the remains were identified as those of Luis Eduardo Arigón. The discovery made him the eighth victim of enforced disappearances during Uruguay’s military dictatorship to be identified since the country’s return to democracy in 1985. The seventh had been found less than 200 yards away and identified a few months earlier as Amelia Sanjurjo. Both had been kidnapped in 1977 over their affiliations with the Uruguayan Communist Party and labor unions; they are suspected to have died shortly after their abduction, tortured by the military.

In the streets of Montevideo, banners and graffiti ask: “Where are they?” Posters of the faces of the disappeared are plastered on walls and windows.

These latest exhumations, in the clandestine torture and burial site known as Battalion 14, were celebrated as victories in the struggle for memory, truth and justice by Uruguay’s civil society groups and state institutions. The process has been painfully slow: The other victims were recovered in 2005, 2011, 2012 and 2019. One victim’s remains were found in 1973 but only identified in 2002. In total, 161 people remain on the list of the forcibly disappeared, according to Alicia Lusiardo, who leads the country’s Investigative Group of Forensic Anthropologists (GIAF). Family members of the disappeared are aging and dying, as are the perpetrators and those who may hold knowledge of what happened to those still missing. In the streets of Montevideo, banners and graffiti ask: “Where are they?” Posters of the faces of the disappeared are plastered on walls and windows.

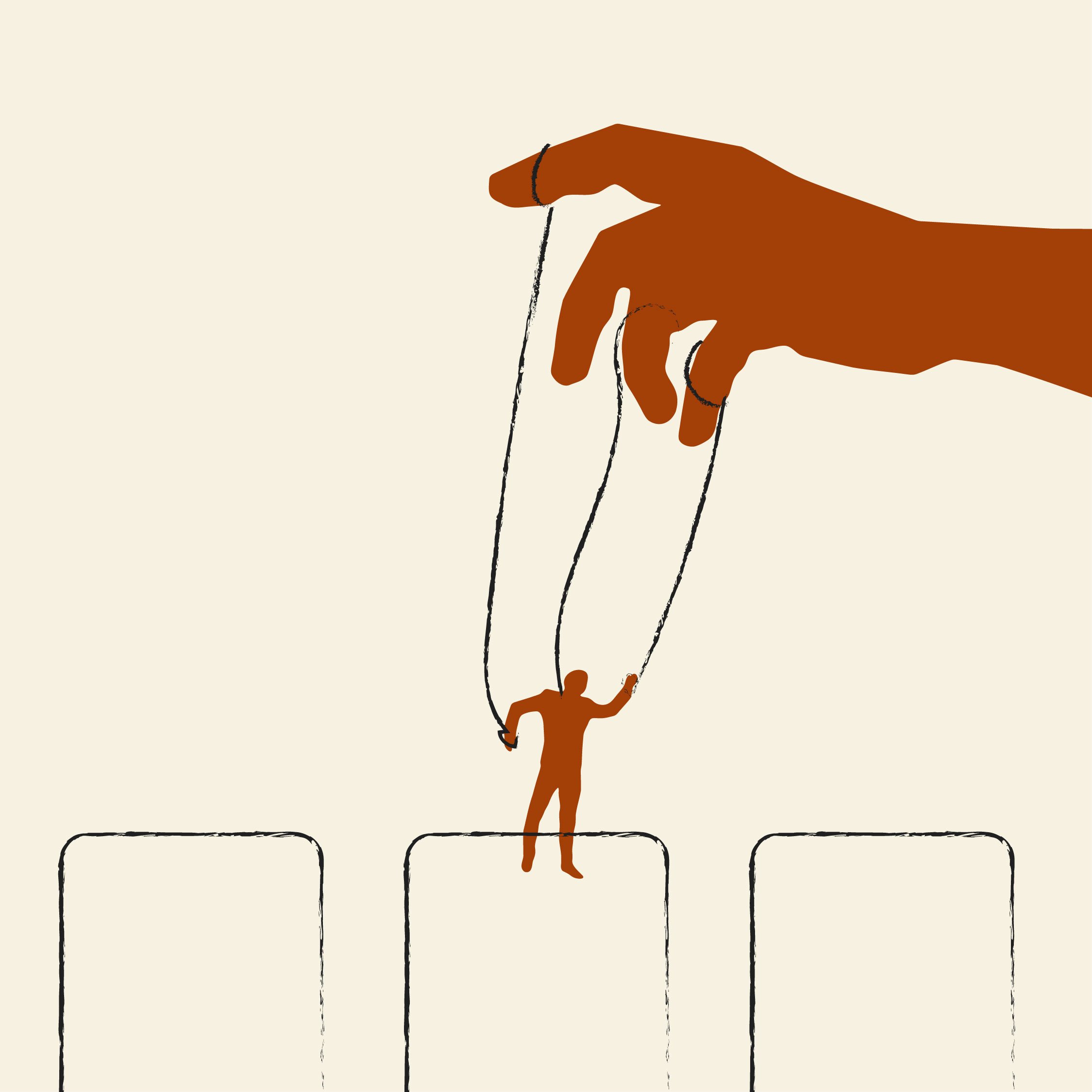

But a pact of silence still reigns among members of the military, and investigators working to uncover the remaining bodies face threats of violence and intimidation, many of them anonymous. According to activists, some of whom are searching for family members, the state is not investing enough in the effort — and even blocking progress.

The pace of discoveries is “worrying,” said Dr. Pablo Chargoñia, lead attorney of the Luz Ibarburu Observatory, a grassroots organization of lawyers which maintains a database of all court cases related to the crimes of the dictatorship and provides legal counsel for victims and their families. “At this rate, the decades needed to find all of the disappeared is a very disappointing mathematical formula.”

✺

Uruguay’s civic-military dictatorship lasted from 1973 to 1985. It was part of a state terror network known as Operation Condor that allowed military dictatorships in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil, Peru and Ecuador to pursue, torture and murder their political enemies across borders, with support from the CIA. Uruguay’s military and police killed 199 of its citizens, arrested around 20 percent of the population, detained more than 10,000 political prisoners and forcibly disappeared 197 people. The state initially targeted leftist guerrillas and communist party militants but later included anyone thought to oppose the regime. Students, union leaders, artists, teachers and even center-right political party members were tortured and killed by the nation’s military and police.

Uruguay, unlike other countries included in Operation Condor, never set up public tribunals to atone for the state’s crimes. Instead, Uruguay’s return to democracy in 1985 brought with it the “Ley de Caducidad,” or “Expiration Law.” This effectively functioned as an amnesty law, protecting members of the military and police from prosecution. The law was seen as ensuring a peaceful transition to democracy and protecting against the threat of another possible coup by the military, which was displeased with the release of political prisoners.

The state didn’t officially recognize its participation in the crimes of Operation Condor until 2000, when then-president Jorge Batlle commissioned a state report on the disappearances, murders and kidnappings that took place during the dictatorship. Searches for the remains of the disappeared did not begin until 2005, when a newly elected left-wing government — led by Tabaré Vázquez of the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) party — granted anthropologists access to lands controlled by military that contain suspected burial sites. “We wasted 20 years of quote-unquote ‘democracy,’” Javier Tassino, an ex-political prisoner and brother of disappeared victim Oscar Tassino, told me.

Uruguay, unlike other countries included in Operation Condor, never set up public tribunals to atone for the state’s crimes.

Since then, the country has made some progress in its efforts to achieve justice for victims. Uruguay annulled the Expiration Law in 2011 and enacted several legislative measures that have benefited the search, including a 2008 law creating the National Memory Archive, a 2009 law recognizing state responsibility for its crimes against humanity and providing monetary compensation to victims, and a 2018 law designating various sites of memory. In 2019, it appointed the National Human Rights Institution and Ombudsman’s Office (INDDHH), an independent, apolitical body, to lead the investigations into the missing bodies of the disappeared. In 2018, the government also created a new office — the Specialized Prosecutor for Crimes Against Humanity — to centralize the prosecution of these crimes, rather than leaving them to be handled individually by lawyers across the country. The strategy is paying off, said Ricardo Perciballe, the office's lead prosecutor. More than 100 perpetrators have been convicted or are currently being tried in the courts. In 2023, Perciballe and his colleagues successfully used the charge of “forced disappearance” to bring three former military members to justice. Although the charge cannot be used retroactively, the court found that the crime is “ongoing” and “continues to be committed until the remains are recovered or [the] fate [of the victim] is known.”

Other government measures have not matched these significant victories on the judicial side. The reparations promised in the 2009 law, for example, are given to an exceedingly narrow category of victims, leaving many of the survivors of enforced disappearance without recourse. These reparations also exclude victims who were minors at the time of their detention as political prisoners. By accepting a payment, beneficiaries renounce all future legal action against the Uruguayan government.

Activists and international groups like the U.N. highlight the need for a coherent and systematic policy to facilitate access to archives and documents belonging to the country’s military, police and intelligence agencies. Currently, documents and information are being hidden, destroyed or withheld from investigators in a bid to obstruct their work, according to activists, families of the victims, investigators and the U.N. Working Group on Enforced Disappearance.

More than 100 perpetrators have been convicted or are currently being tried in the courts. In 2023, Perciballe and his colleagues successfully used the charge of “forced disappearance” to bring three former military members to justice.

Trust in the state and its willingness to address previous wrongs is also low. State officials and members of the military are known to have lied in official reports, including the 2000 Peace Commission report, and in public comments about the number of disappeared and their fates. The first democratically elected president after the dictatorship, Julio María Sanguinetti, falsely claimed that no children had disappeared. His successor, Luis Alberto Lacalle, father of current president Luis Lacalle Pou, said “barely half a dozen” had disappeared. “They’ve lied many times to the families,” said Wilder Tayler, director of the INDDHH. “There’s a break in trust.”

The biggest obstacle facing investigators working to locate and exhume the bodies of the missing is the “pact of silence” observed by members of the military for the past 50 years. According to Tayler, “if the perpetrators would talk, in a month we’d finish this matter.”

As many as 42 more victims may be buried at Battalion 14, according to testimonies and official investigations, but the site’s immense 1,008 acres make for a long and painstaking search.

Members of the military — as well as anonymous tipsters — have engaged in deliberate misinformation campaigns to mislead investigators and exhaust already scarce resources. Tayler called this deliberately false information fruta podrida, or “rotten fruit.” As part of the 2000 Peace Commission, for example, military members and witnesses testified that the bodies of the disappeared buried on military lands were exhumed, cremated and dispersed over the River Plate, in an operation known as “Operation Carrot,” meant to conceal any human rights violations carried out under the dictatorship. Anthropologists and investigators still disagree on whether Operation Carrot happened or whether it’s a fabrication aimed at discouraging investigations. The bodies of several victims specifically named as having been cremated as part of Operation Carrot — including Arigón and Sanjurjo — have been recovered in the 20 years since investigations began.

Alicia Lusiardo, the head of GIAF, said in an interview with La Diaria that she doesn’t believe Operation Carrot truly took place, in part because the perpetrators went to great lengths to conceal the people they killed and buried, making it unlikely they would be able to exhume them all. Her team is currently working in Battalion 14, the site where the remains of four victims were recovered within a 200-yard radius but decades apart — delays, she explained, that are largely due to misinformation and false testimonies, as well as the different strategies employed by lead anthropologists. GIAF’s former lead anthropologist, José López Mazz, based his excavation strategy on a combination of witness testimony, soil disturbances and aerial photography. Lusiardo said that she prefers to excavate the entirety of the search areas, plot by plot. As many as 42 more victims may be buried at Battalion 14, according to testimonies and official investigations, but the site’s immense 1,008 acres make for a long and painstaking search. The excavation process has frustrated both the investigators and the families of the disappeared — particularly as Battalion 14 is just one of many possible clandestine burial locations.

The organization coordinating the search, INDDHH, often receives tips about bodies buried under casinos, multi-story buildings and other similarly difficult locations, in a bid to waste time and resources, according to Tayler. On several occasions, former military members led investigators to purported burial sites, only for them to be found empty.

Requests for documents or resources can take years to be answered, stalling the work of his small investigative team.

Investigators, civilians and officials working to find the disappeared are also routinely subject to threats, intimidation and violence. A 2019 report cited “permanent harassment” and “constant interference” in the search areas by “people, drones, livestock, robberies, and planted objects,” including, on one occasion, an explosive device that caused the suspension of excavations. Memorials and monuments associated with victims of the dictatorship are frequently vandalized and destroyed, incidents that are rarely investigated. In 2024, a relative of disappeared victim Oscar Tassino received a threatening message on his car, “I know where they are, and you could end up the same.”

✺

Despite the promises made in the 2019 electoral campaign, the current administration — headed by Luis Lacalle Pou of the center-right National Party — has done little to advance investigations. When he came to power, Lacalle Pou apologized for his past statements as a senator when he called for an end to the search for the disappeared. He expressed a commitment to do “whatever possible” to support the investigations. But activists claim he’s done the opposite, saying he stopped responding to meeting requests from the activist group Madres y Familiares de Uruguayos Detenidos Desaparecidos (Mothers and Relatives of Disappeared Uruguayans, or Famidesa). He ignored documentation submitted by Famidesa revealing the location of classified military archives, which are thought to hold information about the burial sites and fates of some of the disappeared, as well as the names of officers and soldiers directly involved in these crimes. He also expressed support for a legislative proposal that would give automatic house arrest, rather than a harsher sentence, to perpetrators convicted of crimes committed under the dictatorship who are over the age of 65 (except in convictions of rape, aggravated homicide or crimes against humanity). In response to criticism from activists, he has claimed to be doing his job “in silence” — in other words, to be working on behalf of the victims behind the scenes.

The government’s policies on the issue have been “sometimes inexistent, sometimes existent but lukewarm,” said Tayler. “There’s a lack of coherent and systematic state policy” that would simplify access to archives and help coordinate between relevant organizations, he said. Requests for documents or resources can take years to be answered, stalling the work of his small investigative team.

Several incidents have also cast doubt on the government’s sincerity about securing justice for victims and their families. In 2023, Lacalle Pou failed to turn up at a public ceremony to recognize the state’s responsibility for the crimes of the dictatorship. As part of a 2021 ruling, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights had found the Uruguayan state responsible for the enforced disappearances of two victims and executions of three others, and had specified that the highest officials from all branches of government must be present at a public “ceremony of recognition.”

In 2024, the activist group Famidesa secured a meeting with National Party presidential candidate Álvaro Delgado and sitting vice-president Beatriz Argimón. During the meeting, they were told that Lacalle Pou had ordered the armed forces to release information regarding the disappeared but that no new information had been found. Famidesa requested to see written proof of the order, but the government has repeatedly extended the deadline for providing it. For many, the government’s reticence highlights the discrepancy between its rhetoric and its actions, deepening their distrust.

✺

Lacalle Pou’s National Party is now on the way out. After winning a general election in 2024, the Broad Front party will return to power in March. Historically, the left-wing party has been more supportive of the search for victims of the dictatorship than other parties: The start of the investigations and all major legislative advances happened under its terms. President-elect Yamandú Orsi has pledged to support further investigations and stressed the need to “accelerate and deepen” the search. His track record as mayor of the Canelones region, in which Battalion 14 is located, is also promising: He has attended inaugurations of monuments to victims of the dictatorship, and worked closely with the INDDHH on the search, providing machinery and personnel.

The latest recoveries of remains and successful prosecutions have created a sense of hope among families still waiting for news. But many caution that an unwillingness from top politicians to directly confront the military means investigators will continue to struggle to uncover the truth. In a November 2024 interview with Brecha, an independent publication in Uruguay, Famidesa representative Elena Zaffaroni, an ex-political prisoner and the wife of a disappeared victim, explained that the state has been reluctant to force the military to comply with the investigations or formally probe the role of the armed forces. “No progress has been made in that regard,” she said. The incoming administration, meanwhile, has not yet outlined in detail how it will advance the search for the disappeared.

Politicians claim to want to turn the page on this sordid chapter of its recent history. But as Ariel Castro, the grandson of recovered victim Julio Castro, noted in a radio interview in November 2024: “Sure, we can turn the page. But we must read it first.” That task cannot be further delayed, Tassino, the brother of a disappeared victim, told me. “It’s been 50 years … In my case, my parents and my three brothers passed away. I’m the last in line.”

PHOTO: Marcha del Silencio 2023 or the March of Silence in Montevido, Uruguay, May 2023. By Artigas Pessio, via Wikimedia. The March of Silence is an annual demonstration commemorating the people detained and disappeared under Uruguay’s last military dictatorship.