Nowhere to Hide

Over the last decade, Tajikistan’s security service has waged a campaign to kill, jail and exile dissenters — even from abroad.

MARCH 5, 2024

On March 5, 2015, Umarali Kuvvatov, a Tajik entrepreneur turned government critic, went with his wife and their two sons to have dinner at the home of another Tajik man living in Istanbul. During the meal, Kuvvatov and his family abruptly fell ill. Suspecting they had been poisoned, Kuvvatov dragged his family out of the house and onto the street, looking for an escape. There, a man approached Kuvvatov from behind and fired a single shot into the back of his head.

Word of Kuvvatov’s assassination rippled through the Tajik diaspora. Almost 2,000 kilometers to the northwest, in Moscow, Ehson Odinaev, a 24-year-old blogger and critic of the Tajik government, heard the news. Odinaev and Kuvvatov had worked closely together. Both men were Tajik dissidents who lived in Russia in the early 2010s, though under different circumstances.

Kuvvatov had been a successful businessman. His energy company, Faroz, supplied fuel for NATO troops in Afghanistan. He once enjoyed close ties to Tajik President Emomali Rahmon. Over the summer of 2012, however, Kuvvatov’s life was upended. His business partner, a son-in-law of Rahmon named Shamsullo Sakhibov, began a monthslong pressure campaign to wrest sole control of Faroz from Kuvvatov, according to a report from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. When Kuvvatov refused to sign papers to transfer the company to Sakhibov, Sakhibov threatened to plant drugs on him. Anonymous callers threatened Kuvvatov’s family. Eventually, Tajik authorities indicted Kuvvatov on trumped-up charges of illegal acquisition of property, illegal financial transactions and illegal detention. Kuvvatov would later leak conversations between himself and Sakhibov as evidence of the shakedown.

Rather than acquiescing, Kuvvatov fled to Moscow and reinvented himself as an outspoken critic of the Tajik regime. He gave interviews to foreign media decrying the Tajik kleptocracy. And most significantly, he founded Group 24, an opposition movement focused on reforming Tajikistan and protecting Tajik migrant workers. The group was largely made up of Tajiks living and working in Russia. Among them was a young Odinaev.

Odinaev’s story is less flashy than Kuvvatov’s. Born in Shahrinav, a town in western Tajikistan, Odinaev left his home country for Russia in 2007, joining his mother and brother in Moscow. He worked, studied and participated in several civil society organizations. In 2012, he became a founding member and active representative of Group 24, part of a small band of media specialists who spread Kuvvatov’s anti-regime messaging online.

Exile did not keep them safe. Their fates exemplify the Tajik government’s campaign of transnational repression and its systematic approach to harassing, kidnapping and imprisoning its enemies abroad.

He blogged under the pseudonym Sarfarozi Olamafruz almost daily on Facebook and started a media platform, Tajikinfo.org, which published updates about the Tajik opposition movement. He also ran a YouTube channel called POLITIKTJ, which still has nearly 50,000 subscribers. The channel posted videos of opposition leaders, mainly Kuvvatov, giving interviews and holding rallies in Europe. Its most popular videos exposed and embarrassed Rahmon’s regime: The video with the most views shows the president, purportedly drunk, singing and dancing clumsily.

In the wake of Kuvvatov’s death, Odinaev decided to move from Moscow to St. Petersburg. It was the first step in his plan to leave Russia for Finland.

On May 19, 2015, Odinaev left his apartment in St. Petersburg. Video surveillance captured him walking toward Kurskaya Street before disappearing out of frame. No one has seen or heard from him since.

When his brother, Vaisiddin, arrived at his apartment, all that was left were Odinaev’s personal belongings, a piece of flatbread, a can of soda and his laptop, open to Facebook. On the outside of the apartment door, Vaisiddin noticed visible marks of two strong kicks.

Odinaev and Kuvvatov were among the many Tajik opposition politicians and government critics who were forced to flee to other countries. But exile did not keep them safe. Their fates exemplify the Tajik government’s campaign of transnational repression and its systematic approach to harassing, kidnapping and imprisoning its enemies abroad.

✺

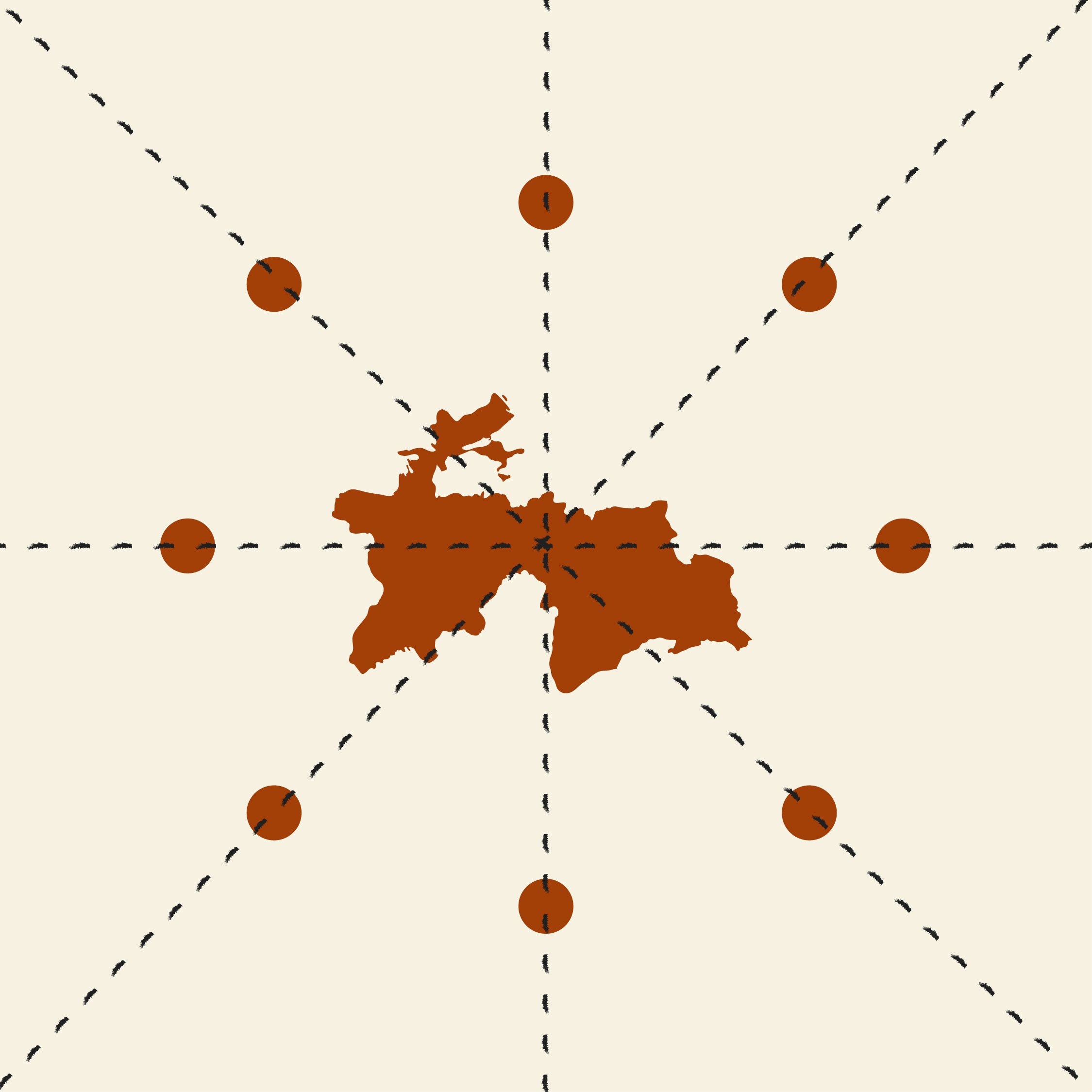

Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the south, Kyrgyzstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west and China to the east. Ninety-three percent of the country is mountainous, making its dramatic terrain difficult to traverse. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan suffered a bloody civil war that still casts a long shadow on the country’s politics and culture.

By the time Tajikistan formally gained independence in December 1991, the country had already begun to fracture ideologically and regionally. Almost all the country’s leaders under Soviet rule were from a political and ethnic alliance based in the northern city of Khujand, the second-most populous in Tajikistan. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, those same elites from the north and their allies tried to maintain control of the government. However, Islamists, nationalists and ethnic minorities from less developed regions in the south and east joined together under a unified opposition bloc to resist their rule.

Mass graves are still being discovered. Many families have never stopped grieving or wondering what happened to their loved ones.

Both the neo-Communists of the north and the opposition took up arms after multiple governments fizzled in the face of disorder in the countryside and widespread protests in Dushanbe, the capital. The neo-Communists and the various strongmen who supported them called their army the Popular Front and won a decisive battle in Dushanbe in 1992. The conflict continued for five more years as the united opposition waged a guerrilla war from the mountains, sometimes finding refuge in northern Afghanistan.

Both the opposition forces and Popular Front fighters have been accused of war crimes and ethnic cleansing. Stories passed down through families detail rape, murder and property destruction. According to Human Rights Watch, the war displaced at least 800,000 people. Many fighting-age men took up arms, and many disappeared, vanishing from bread lines or while out walking the streets. U.N. investigations have since found evidence of the use of clandestine detention centers and informal prisons during the war. Mass graves are still being discovered. Many families have never stopped grieving or wondering what happened to their loved ones.

Reports of the death toll vary widely: Estimates range from 25,000 to as high as 157,000 casualties between 1992 and 1997. The U.N. Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has estimated that thousands of individuals may still be unaccounted for. There has not been an attempt to collect a full list of those dead or disappeared — largely because the leaders of the Popular Front, which perpetrated much of the violence, are still in power today.

“Wounds remain deep, but go intentionally ignored,” the U.N. group wrote in a report following a 2019 visit to the country.

The Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in 1996 sent shock waves through the region. Russia, Iran and the other Central Asian republics urgently cajoled the Popular Front to agree to a deal with the opposition to shore up Afghanistan’s northern border with Tajikistan. In 1997, the Popular Front and the opposition signed a peace agreement that allotted 30 percent of seats in the newly formed government to the opposition.

Emomali Rahmon, once the head of a Soviet farming collective, was chosen by the Supreme Soviet, the main legislative body of the former Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, to be the political leader of the Popular Front in 1992. At the time, he was widely viewed as a figurehead whose power derived from the militia commanders backing him. But during the civil war, and in the nearly thirty years he’s been in power since, he has proved to be adept at marginalizing and eliminating those who question his rule. Now 71, Rahmon has spent the decades after the peace agreement tracking down military opponents left over from the civil war and the political critics who have emerged since.

“You could basically say the civil war never ended,” said Marius Fossum, the Central Asia representative for the Norwegian Helsinki Committee. “Since the peace agreement, the [Tajik] authorities have been pursuing their opponents through different means.”

Today, Rahmon’s consolidation of the economy and chokehold on dissent is nearly absolute. Members of his family own or control wide swaths of the country’s economy, including the aluminum mining, entertainment, major retail, air transportation, finance and media industries. Tajikistan was ranked as the eighth least free country in the world by Freedom House in 2024 — the predictable and intended result of Rahmon’s yearslong campaign to crush civil society, independent media and legitimate opposition parties.

“The government has tried to cultivate a sense of not just apolitical citizens but anti-political citizens,” said Edward Lemon, a research assistant professor at Texas A&M University’s Bush School of Government and Public Service who specializes in Central Asian autocracies.

Through court records, U.N. reports and interviews with family members of the disappeared and those who have survived kidnappings, the network pieced together how the Russian and Tajik security services conduct these covert operations.

Critics who have fled to Russia have been the easiest targets for the regime. Russia’s FSB and Tajikistan’s GKNB — successors to the KGB, the Soviet Union’s secret police and intelligence agency — work closely together. The two organizations use the extradition system as scaffolding to locate and then disappear targets.

An informal international network of academics, journalists and human rights activists has spent years tracking the Tajik dissidents who have disappeared from Russia over the last two decades. The network includes Lemon, Fossum and Steve Swerdlow, an associate professor at the University of Southern California who published one of the most detailed reports on the disappearances of Tajiks abroad last fall. Through court records, U.N. reports and interviews with family members of the disappeared and those who have survived kidnappings, the network pieced together how the Russian and Tajik security services conduct these covert operations.

It works like this: First, the Tajik government submits a formal request for an individual living in Russia to be extradited. Russian police arrest the person in question and take them to a pretrial detention center. After appearing before a judge, the person is released, at which point agents of the FSB or GKNB, or both, kidnap, beat and detain the target. The transportation methods vary — a leader of Group 24 named Maksud Ibragimov was sent back in the baggage hold of a plane — but the person always ends up back in Tajikistan. After a sham trial, they are sentenced to lengthy prison terms. In 2015, Ibragimov was sentenced to 17 years in jail and remains imprisoned in Tajikistan.

On April 17, Tajik law enforcement officials picked up Iskandarov from Dushanbe International Airport. He was imprisoned under a false name, beaten, drugged and forced to make a false confession. Then he was sentenced to 23 years in prison.

In 2005, Mahmadruzi Iskandarov, the exiled leader of the Democratic Party of Tajikistan and a longtime critic of Rahmon, was kidnapped by Russian authorities. He fled to Russia five days after the Tajik General Prosecutor’s Office charged him with terrorism, gangsterism, unlawful possession of firearms and embezzlement. The same day that he left Tajikistan, the Tajik Prosecutor General’s Office sent an extradition request for Iskandarov to its Russian counterpart. From December 2004 to April 2005, Russian authorities held Iskandarov in detention while he fought his extradition. In April, the Russian Prosecutor General’s Office waived the extradition request, and Iskandarov was released.

Once freed, Iskandarov stayed with a friend in Korolyov a town outside of Moscow. According to his official account to the European Court of Human Rights, on April 15, while out walking a dog, Iskandarov was surrounded by a group of “twenty-five or thirty men with Slavic features wearing civilian clothes” and two police officers. The men kidnapped and beat Iskandarov before escorting him to an airport, where he was put on a flight to Dushanbe.

On April 17, Tajik law enforcement officials picked up Iskandarov from Dushanbe International Airport. He was imprisoned under a false name, beaten, drugged and forced to make a false confession. Then he was sentenced to 23 years in prison. In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Russia had violated the European Convention on Human Rights and ordered the Russian state to pay Iskandarov 33,000 euros. Iskandarov, however, is still serving his sentence in Tajikistan.

In the nearly 20 years since Iskandarov’s forced return to Tajikistan, extraordinary renditions have only become more frequent. Since 2020, at least seven prominent Tajik activists or government critics have been sent back to Tajikistan from Russia, according to Swerdlow’s report.

Other authoritarian governments are all too happy to oblige the Tajik government’s extradition requests with the understanding that if a political dissident chooses to flee to Tajikistan (an unlikely but not impossible event), the favor would be returned.

Tajikistan’s membership in multiple collective security organizations, including the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, facilitates the extradition process. For example, take the SCO, which boasts Russia, China, Iran and India as member states. Within the SCO, there is a separate body called the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure. The RATS charter specifies that no country in the SCO can provide refuge for an individual subject to an extradition request by another member state. All that is required to put an individual on an extradition list is a court order. And in Tajikistan, every judge is under Rahmon’s thumb. (The country’s last somewhat fair-minded judge, Rustam Saidahmadzoda, was put on trial behind closed doors last year.)

Other authoritarian governments are all too happy to oblige the Tajik government’s extradition requests with the understanding that if a political dissident chooses to flee to Tajikistan (an unlikely but not impossible event), the favor would be returned. The extrajudicial kidnappings simply speed up the inevitable extradition and, crucially, deprive the international human rights community from having the chance to rally while the case makes its way through court.

✺

For Muhiddin Kabiri, the long-exiled leader of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, once the country’s most powerful and popular opposition group, the map of the world is demarcated by places he can and cannot go. Russia, along with the rest of the post-Soviet world, is obviously not safe. Turkey is a no-go. At one point, he could go to Malaysia; however, the Malaysian government has informed him that due to a new bilateral security agreement with Tajikistan, he can no longer travel there lest he face extradition. A few years ago, he wanted to go to Iran to visit his brother; his visa was denied.

To date, the Tajik government has not successfully kidnapped any of its opponents in Europe. But that does not mean it has not tried.

The IRPT once had over 50,000 members, held seats in the Tajik parliament and operated regional offices throughout the countryside. It not only represented an alternative to the Rahmon government’s kleptocracy but also provided social services to regions ignored by Dushanbe. In 2015, the Tajik government cracked down on the IRPT, declaring it a terrorist organization. Hundreds of IRPT members were jailed. Many were tortured. Kabiri fled the country before he could be detained on trumped-up charges.

Kabiri now lives in Europe. I did not ask which country, and he was careful not to let any details of his whereabouts slip during our conversation on Signal, an encrypted messaging app.

To date, the Tajik government has not successfully kidnapped any of its opponents in Europe. But that does not mean it has not tried.

In 2020, Ilhomjon Yakubov, a former regional leader of the IRPT, was the victim of an attack by Tajik operatives on European soil, according to a dispatch from Human Rights Watch.

Yakubov agreed to meet a former business partner visiting from Tajikistan to discuss the plight of Tajik political prisoners in Kaunas, a city in eastern Lithuania. When the former business partner picked up Yakubov, he was not alone. Another man was waiting in the back seat. After driving for a while, Yakubov asked to be let out. The driver refused and locked the car doors. The man in the back seat, whom Yakubov did not know, shouted that he was going to kill Yakubov. The two men beat Yakubov, giving him two black eyes. The fight spilled onto the street, where the beating continued. The two men were trying to force Yakubov back into the car when a Lithuanian police car approached, stopping the attack. Lithuanian authorities are still investigating the incident.

Kabiri said he has also had brushes with Tajik agents in Europe.

In 2018, Kabiri traveled to Warsaw to attend the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s annual Human Dimension Implementation Meeting. During the panels on human rights abuses and media restrictions in Tajikistan, he met a man who was registered as the chairman of a migrant rights organization from the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, Russia. The two men met twice and mingled with other activists.

After the conference, Kabiri had plans to travel to Berlin. Coincidentally, the man from Krasnoyarsk was going to Berlin, too — on the same train line, at the same time, with a reserved ticket in the same coupé as Kabiri. Kabiri’s security team became suspicious. They took a photo of the man and sent it to contacts in Dushanbe.

Hours into the train ride, they received a message back: The man was a member of the Tajik secret police. When Kabiri confronted him, the man folded and admitted that he had been sent by the head of the GKNB to gather information about Kabiri’s whereabouts. He then pleaded for Kabiri to help him apply for asylum in Europe.

Kabiri estimates that there are only about 20,000 Tajiks in Europe. Connecting with someone from home is rare and tempting. But there is always a risk that they might be an emissary from Rahmon, who has sent operatives to Europe posing as refugees, migrants, students, embassy officials and human rights advocates.

Muhamadjon Kabirov, a Tajik immigrant rights advocate and director of the independent media organization Azda.tv, covers nepotism, corruption and torture in Tajikistan. Even though the company operates from Poland, the work has put Kabirov in Rahmon’s crosshairs.

He said he’s had to move twice after Tajik authorities discovered his home address. He’s had to move the Azda.tv offices once as well. He asks his children’s school not to publish any photos or personal information about his family online. He switches up the routes he takes to work. He does not wear headphones in public. When he and his family order a taxi, they check to see if the driver has a Tajik name. If the driver does, they cancel the ride.

✺

On March 9, 2015, Umarali Kuvvatov’s body was driven through Istanbul. One of his supporters captured the journey on video. The procession stopped at a mosque, where his family, friends and followers prayed and then spoke to the media. His children held up signs with his photo and the word şehîd, which translates to “martyr.” They later helped bury their father on a hillside in Kilyos Cemetery.

Sulaimon Qayumov, the man who allegedly poisoned Kuvvatov and his family at dinner, fled to Kazakhstan the same night Kuvvatov was murdered. Kazakh authorities stopped him at the airport and sent him back to Turkey, where prosecutors charged him with homicide. In 2016, Qayumov was sentenced to life in prison. According to an article published by the Russian news agency Fergana, four other Tajik nationals suspected to have taken part in the assassination fled Turkey before they could be apprehended. All four were tried and sentenced in absentia.

“As a human rights advocate and activist, I believe the worst has happened to [Ehson],” he added. But “[as] his brother, I hope nothing bad happened to him.”

Ehson Odinaev’s brother, Vaisiddin, searched for him after he disappeared. He called the police to make a missing persons report, but the Ministry of Internal Affairs in St. Petersburg refused to help. Over Signal, Vaisiddin said it appeared to him as if the police knew what had happened and slowed down the process intentionally. He asked Tajik government officials about Ehson’s case, but they declined to comment.

Vaisiddin has picked up where his brother left off by continuing to work as a human rights defender and critic of the Tajik regime. In 2016, he took part in a protest during Rahmon’s visit to the Czech Republic. The crowd held up signs that read: “Rahmonov! Don’t Run from the People.” (“Rahmonov” is the Russian patronymic form of “Rahmon.”)

Tajik security officers in plainclothes approached Vaisiddin, threatened to kill him and the other protesters, and promised to go after their relatives in Tajikistan.

Six days later, Tajik police detained Odinaev’s grandfather in the small city of Hisor. They interrogated the 75-year-old for five hours about Vaisiddin’s role in the opposition.

Vaisiddin said he hopes that the European Union and the United States will respond to Rahmon’s regime by sanctioning key Tajik officials, ceasing international financing of government projects and suspending diplomatic relations with Tajikistan until the thousands of prisoners of conscience are released. “It probably sounds like a dream,” he wrote on Signal.

“As a human rights advocate and activist, I believe the worst has happened to [Ehson],” he added. But “[as] his brother, I hope nothing bad happened to him.”