What Do We Owe the Dead?

International human rights law only recognizes the rights of the living.

JANUARY 28, 2025

In 2020, Tishiko King returned to her native Masig Island in Australia’s Torres Strait to survey the damage wrought by climate change. In the 20 years since she last lived there, warming waters had diminished traditional fishing grounds and made life hard for indigenous Kulkalaig. Rising sea levels also threatened the home of future generations. But King’s homecoming forced her to confront how the climate crisis had ravaged another group: the dead.

Walking along a familiar beach, she noticed that the shifting tides had eroded burial grounds and exposed the remains of her ancestors. “We actually picked up the bones of one of my grandmas, like seashells on the beach,” King said in a talk at the University of Sydney last year.

What could King do about this, legally speaking? Could the law have protected her grandmother from such indignity in death, or protected King from this disturbing discovery? Did her grandmother’s rights as a human being die with her?

These are unsettled questions. Debates about what we owe the dead have persisted for millennia, yet the law offers incomplete and unsatisfying answers. “Universally, human beings care deeply about respecting the dead, and, universally, we violate the rights of the dead,” said Anjli Parrin, director of the Global Human Rights Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School. “These two truths sit uncomfortably next to each other.”

Despite a shared belief that the dead deserve dignity, there are huge gaps in the protections that international law offers them. “In international human rights law in particular, there's nothing, virtually nothing,” Morris Tidball-Binz, the United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, told me. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which serves as the foundation of international human rights law, applies only to the living; there is no equivalent for the dead.

Nor is there legal consensus that international law could or should mandate human rights for the dead, outside of wartime. (International humanitarian law, the body of law that lays out protections during armed conflict for certain categories of people, such as prisoners of war and civilians, does recognize the dead as having rights.) In a 2020 article called “What Remains? Human Rights After Death,” Claire Moon, a sociologist at the London School of Economics and Political Science, describes asking international lawyers and forensic scientists two questions: Do the dead have human rights? And if so, which rights do they have? The responses she received were “wildly varying,” ranging from “What a ridiculous question! Only the living can have human rights!” to “What a ridiculous question! Of course, the dead have human rights!”

Debates about what we owe the dead have persisted for millennia, yet the law offers incomplete and unsatisfying answers. “Universally, human beings care deeply about respecting the dead, and, universally, we violate the rights of the dead,” said Anjli Parrin.

If the jury is still out, however, there are signs that the deliberation is making progress. The world’s foremost international legal institutions, chief among them the U.N., are seriously grappling with the question of what we owe the dead, as legal scholars and forensic anthropologists develop standards and guidelines for their protection. Sometimes called “soft law documents,” these include a U.N. text that gives guidance on how to put into practice the duty to protect life and investigate potentially unlawful deaths, and a similar text developed in association with the International Commission on Missing Persons that sets out rules and practices for protecting and investigating mass grave sites. International and regional human rights courts have also recently affirmed various rights of the dead in countries including Guatemala and Colombia.

Developing international laws that explicitly protect the dead outside of war — rather than leaving it to individual nations to determine their own protections, or to international laws that refer to the dead implicitly — is crucial work. Such protections allow international courts to prosecute national governments within their jurisdiction for violations. They also establish a standard that can guide nations as they develop their own laws. The current lack of universal rights and protections for the dead is particularly harmful for marginalized groups, such as migrants and LGBTQ people. As Tidball-Binz wrote in a U.N. report last summer, “Many of the inequities, discrimination and injustices that occur in life continue to persist in death.”

✺

Luis Fondebrider knows where the bodies are buried. A pioneer of the field of forensic anthropology, in 1984 he founded the Equipo Argentino de Arqueología Forense, a group of students that applied innovative forensic scientific techniques to recover and identify “the disappeared” and other victims of Argentina’s military dictatorship. Since then, his work has taken him to international tribunals and other inquiries into the missing in more than 60 countries.

Fondebrider believes that every culture observes rituals around at least four stages: birth, entering adulthood, marriage, and finally, death. “It’s a human need not related to a specific religion, culture, or ideology,” he told me over Zoom from The Gambia, where he was training members of the government on how to look for missing persons. “When someone, as a consequence of a violent death, cannot recover the body, cannot see the dead, cannot bury them properly according to their rituals, it's an alteration of reality for that person, for that family, for that village.” He has countless stories to back this up. “After 20 or 30 years, when you give back the body to the family, it's like the person died that day,” he said. “Around the world, I go to the houses of the families [of the missing] and they have the room of the boy or the girl in the same condition when they disappeared 20 years ago.” Once when returning a body to a family, a mother kept touching Fondebrider’s hands, so he asked why. Because you were touching the body of my son, she replied.

Parrin, in her work reviewing legal frameworks on the protection of the dead around the world, likewise struggled to find a single community that lacked reverence for the dead. It’s this universality that makes protections for the dead better suited to international law, rather than simply national laws, she believes.

This same logic, in part, underpinned the development of international humanitarian law’s protections for the dead during war. Most of the international rights and protections for the dead that currently exist belong to this older, more codified body of law.

Today, requirements to identify the war dead in accordance with international humanitarian law and return them to their families are often the only things warring rivals can agree on. This past November, Russia returned the bodies of 563 members of the Ukrainian military who were killed in Donetsk or Bakhmut, or had been in morgues on Russian territory. In return, Ukraine sent home the bodies of 37 Russian soldiers.

The history of war is full of stories of identifying or returning the war dead, which can happen even decades after the guns go quiet. In 1982, the United Kingdom and Argentina went to war over a cluster of islands about 300 miles from the east coast of Argentina that are known in the U.K. as the Falklands and in Argentina as the Malvinas. The British took control of the islands after 10 weeks, and the fighting came at the price of hundreds of lives on both sides. After the hostilities ended, a British army captain named Geoffrey Cardozo spent six weeks helping build a cemetery for the dozens of fallen Argentinian soldiers that British forces found scattered — sometimes half-buried — throughout the islands. Before burying the bodies, Cardozo recorded any identifying markings, as well as where each body had been found, and where it was buried. “I am an army officer, I am a soldier,” Cardozo said, “but before everything else I am a human being.”

Once when returning a body to a family, a mother kept touching Fondebrider’s hands, so he asked why. Because you were touching the body of my son, she replied.

To be sure, warring sides often ignore international humanitarian law, and the obligations toward the dead that it demands. In the past year, for example, there have been reports of the Israeli military desecrating cemeteries in Gaza, as well as corpses left in the streets for stray dogs to scavenge.

Even so, the existing baseline for how the dead should be treated during wartime, set out in international humanitarian law, is essential. Militaries base their manuals on these legal obligations, and international courts can bring cases against countries or individuals who fail to live up to them. Extending or strengthening international rights for the dead in times of peace, too, might likewise push countries to bolster their national protections.

“Having peacetime principles isn’t going to prevent violations — just as me saying that there's an absolute prohibition of torture is not preventing torture — but it's at least admitting that there is a role [for human rights of the dead],” said Parrin.

Though international human rights law contains no explicit rights that protect a dead body, rights for the dead can sometimes be inferred from broader rights that exist for the living. For example, the rights to life and to be protected from enforced disappearance oblige states to protect and preserve the remains of someone killed unlawfully or buried in an unmarked mass grave. In fact, as Tidball-Binz’s U.N. report points out, investigating a possible unlawful killing is part of a state’s duty to uphold the right to life, under international human rights law.

Who counts as family? The law doesn’t have good answers. “It's thought of largely as biological families, but that leads to discrimination of LGBTQ folks and other social families,” said Parrin. And many of the dead, namely the unclaimed or unidentified, have no families at all to fight for those rights.

International human rights law, and national laws, also recognize rights held by the family of the dead. Most jurisdictions, for example, uphold some form of a family’s right to a dignified burial for loved ones. This is true at the international level too. In two cases from Nepal, initiated in 2012 and 2014, the U.N. Human Rights Committee — an independent body that monitors compliance with international human rights law — found that cruel, inhuman treatment of human remains amounted to cruel, inhuman treatment of the family of the deceased. Regional courts such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights have reaffirmed these protections and the rights of family members.

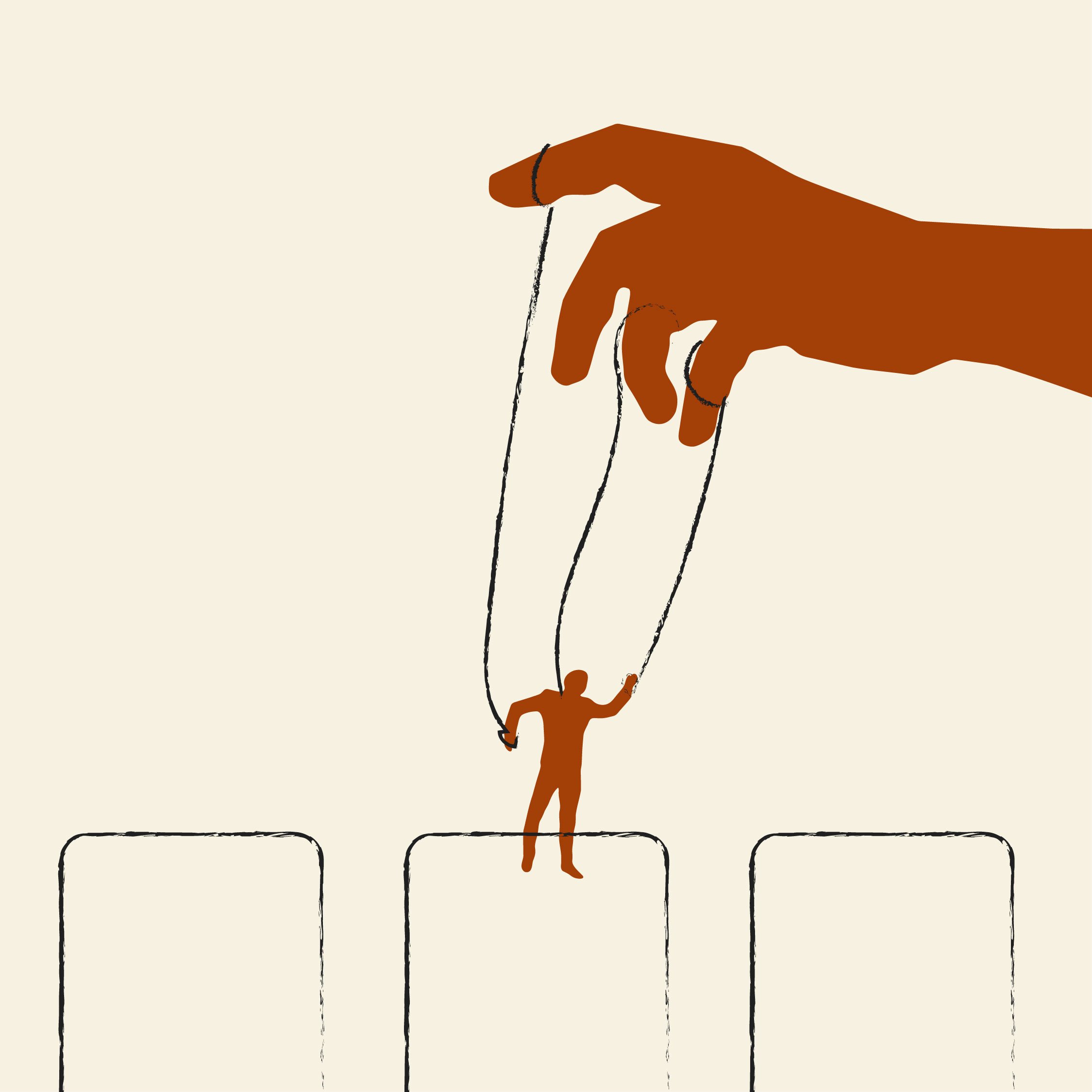

But this legal framework, which relies on inferring human rights of the dead from the rights of the living, is insufficient. In thinking of the rights of families of the dead, there’s a significant snag: Who counts as family? The law doesn’t have good answers. “It's thought of largely as biological families, but that leads to discrimination of LGBTQ folks and other social families,” said Parrin. And many of the dead, namely the unclaimed or unidentified, have no families at all to fight for those rights. In other cases, governments lack either the capacity or the will to track down the deceased’s next of kin, especially for the remains of people deemed unworthy or undeserving of protection to begin with.

This is why some scholars, such as Ximena Londoño, a legal adviser at the International Committee of the Red Cross, argue that a fundamental aspect of existing wartime protections for the dead, in international humanitarian law, is that “treatment of the dead is related to the dead themselves and not to the relatives [of the dead].” In other words, someone who dies during an armed conflict has the same rights whether or not they have family who miss them, and whether or not their identity is known. Scholars such as Parrin hope to establish the same kind of equality under international human rights law.

✺

The lack of explicit protections for the dead in international human rights law creates difficulties beyond defining familial boundaries. Consider one investigation from 2020 that found that 39,000 unidentified and unclaimed bodies languished in Mexico’s morgues after the government started to deploy the military to crack down on organized crime and drug traffickers in 2006. As the militarized response created power vacuums and turf wars, murder rates soared, and morgues grew overwhelmed. In 2018, a trailer parked in a suburban neighborhood of Guadalajara was only discovered by the stench of the 273 bodies decomposing inside of it. Other bodies were buried in unmarked graves without proper postmortems or given to medical schools with no consideration for the wishes of the deceased. The federal government only began its first real effort to identify the dead and the missing a few years ago — an undertaking that some estimate could take forensic scientists 120 years to complete.

The discovery of the mass graves in Tunisia, as well as the country’s other apparent mistreatment of the dead, made global headlines. Despite the moral outrage, however, it wasn’t clear that a crime had been committed: There’s no agreed upon definition of a mass grave in international human rights law.

Or consider the thousands of migrants who die before reaching their destination. After civil war broke out in Libya in 2011, Tunisia threw open its gates to more than 1 million refugees and other migrants, earning praise from advocacy groups. However, that generosity waned over the years, and drowned migrants began to wash up on Tunisia’s shores. In 2019, human rights groups criticized Tunisia for reports of unidentified migrant corpses carried in garbage trucks and then dumped in concealed mass graves after officials refused to allow their burial in local cemeteries.

The discovery of the mass graves in Tunisia, as well as the country’s other apparent mistreatment of the dead, made global headlines. Despite the moral outrage, however, it wasn’t clear that a crime had been committed: There’s no agreed upon definition of a mass grave in international human rights law. In 2023, one migration researcher told The Guardian that even when Tunisian coroners conduct autopsies on the bodies of asylum seekers, in order to determine a cause of death, they make no attempt to establish the dead person’s identity, because they have no legal obligation to try to do so. If “there are no family members who report a disappearance,” he said, “the identification becomes ‘irrelevant’ for the authorities.”

What happened in Tunisia perfectly illustrates the connection between injustice and discrimination in life and in death. It’s an insight that motivates the recommendation in Tidball-Binz’s U.N. report to establish “guiding principles for protection of the dead through a human rights lens” — essentially, something akin to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights: a Universal Declaration on the Dignity of the Dead. Only universal rights, applied without prejudice or regard to categories of people, can fill the gaps in protection through which migrants and other marginalized groups often fall, in both life and death.