Germany’s Crackdown on Civil Liberties

The Israel-Hamas war has exposed tensions about who has the right to assemble and speak freely in the country.

NOVEMBER 16, 2023

State of the World features occasional dispatches on the latest news, events, and ideas. To receive these updates directly in your inbox, sign up for our newsletter.

✺

This week, Ben Mauk is reporting from Berlin, Germany.

Thousands of demonstrators took to the streets of Berlin’s central district on November 4, 2023, for a pro-Palestinian rally. (Sipa USA via AP)

“At this moment, there is only one place for Germany,” the nation’s chancellor, Olaf Scholz, said on October 12, five days after a Hamas attack in southern Israel killed 1,200 people. “The place on the side of Israel.” He has kept his word. Israel’s strongest European ally immediately suspended $131 million in development aid to the Palestinian territories, money earmarked to help with desalination projects, job creation and food security. Like others in his cabinet, Scholz has made a point to repeat the claim made famous by his predecessor, Angela Merkel, that supporting Israel is part of Germany’s Staatsraison — its foundational purpose — a legacy of the Nazi era which marks Germany as a nation forever making amends with its former victims. “Essentially this is about keeping the promise given again and again in the decades since 1945 … the promise ‘never again’,” Scholz said at a November 9 speech to commemorate the 85th anniversary of the Nazi pogrom known as Kristallnacht.

But in the wake of Israel’s invasion of Gaza in which more than 11,000 people, nearly 5,000 of them children, have been killed, Germany’s special sense of responsibility has exposed tensions at the country’s core. Although the German constitution protects the right to assembly, in the days following the start of the war, the government banned nearly all public expressions of solidarity with Palestine. Some cities, such as Hamburg, explicitly banned assemblies related to Gaza. In Berlin, home to one of the largest Palestinian diaspora in Europe, authorities cancelled rallies ad hoc and sent riot police into neighborhoods with migrant populations to suppress any spontaneous expressions of protest or grief. Some bans were justified on the grounds that protests would “emotionalize” locals. Videos emerged on social media of officers arresting and often violently detaining people carrying Palestinian flags, wearing the keffiyah scarf associated with Palestinian activism, or holding anti-war signs. Those detained included a well-known Syrian activist, Jewish Israelis, and several children.

The assemblies that did take place were therefore unsanctioned. On the evening of October 18, more than a week after the bombardment of Gaza had begun, I observed one such unauthorized protest on Sonnenallee, a main artery of Arab and Muslim life in the Berlin neighborhood of Neukölln, where I happen to live. For several days, the neighborhood had felt under police occupation, with armed patrols and police vans a constant part of public life. At the demonstration, I watched dozens of riot police incite and escalate conflicts with protesters, beating and brutalizing those who were chanting “free, free Palestine” in the street or holding Palestinian flags. When I attempted to film the particularly violent arrest of a Palestinian flag-waver, I was maced by a police officer while holding my press credentials in my hand.

A swell of protest has followed Germany’s crackdown on civil liberties. Even among the country’s leadership, some have quietly voiced concerns that authorities are going too far. The first federal commissioner tasked with fighting antisemitism, Felix Klein, told The Guardian he was concerned the right to peaceful protest was being curtailed. “Because of course demonstrating is a basic right.”

These internal contradictions are hardly new. Journalists and politicians in Germany routinely conflate the State of Israel and Jewish people, often using the terms interchangeably. When authorities identified the remains of Vivian Silver, an Israeli-Canadian peace activist killed on October 7, a public German news broadcast misquoted a Canadian minister as claiming “the world was losing a prominent advocate for peace between Jews and Palestinians.” A Green Party leader lamented the lack of public support for Germany’s “special responsibility for the security of the State of Israel” by emphasizing the importance of “a clear stance against antisemitism in all its forms.” German Social Democratic Party leader Saskia Esken boycotted an event with Senator Bernie Sanders, members of whose family were murdered in the Holocaust, over Sanders’s statement in the early days of the war: “The targeting of civilians is a war crime, no matter who does it.” For this, Esken claimed, Sanders had not “stood on the side of Israel and against the terror of Hamas.”

It is also common to hear criticism of Israel described as antisemitic, a fact that has resulted in the paradox of the German state actively suppressing those Jewish voices that do not conform to their expectations. A state-owned cultural center, Oyoun, faces defunding by the Berlin Senate for hosting an evening of “mourning and hope” put together by Jewish Voice for Just Peace in the Middle East, a Jewish organization. On November 9, the city of Frankfurt on Main forbade a planned rally called “Never again fascism – remembering Kristallnacht, fighting anti-Semitism,” apparently due to the organizer’s past support for Palestine. The police continue to selectively enforce bans on such phrases as “stop genocide,” “free Palestine,” and “stop the war,” often with no prior announcement. A sanctioned protest in Berlin on November 10, organized by a coalition of Jewish and Israeli groups, resulted in several arrests due to the sudden mid-protest banning of some of these phrases. They included the arrest of a Jewish-Israeli woman who held a sign that read: “As a Jew and Israeli: Stop the Genocide in Gaza.”

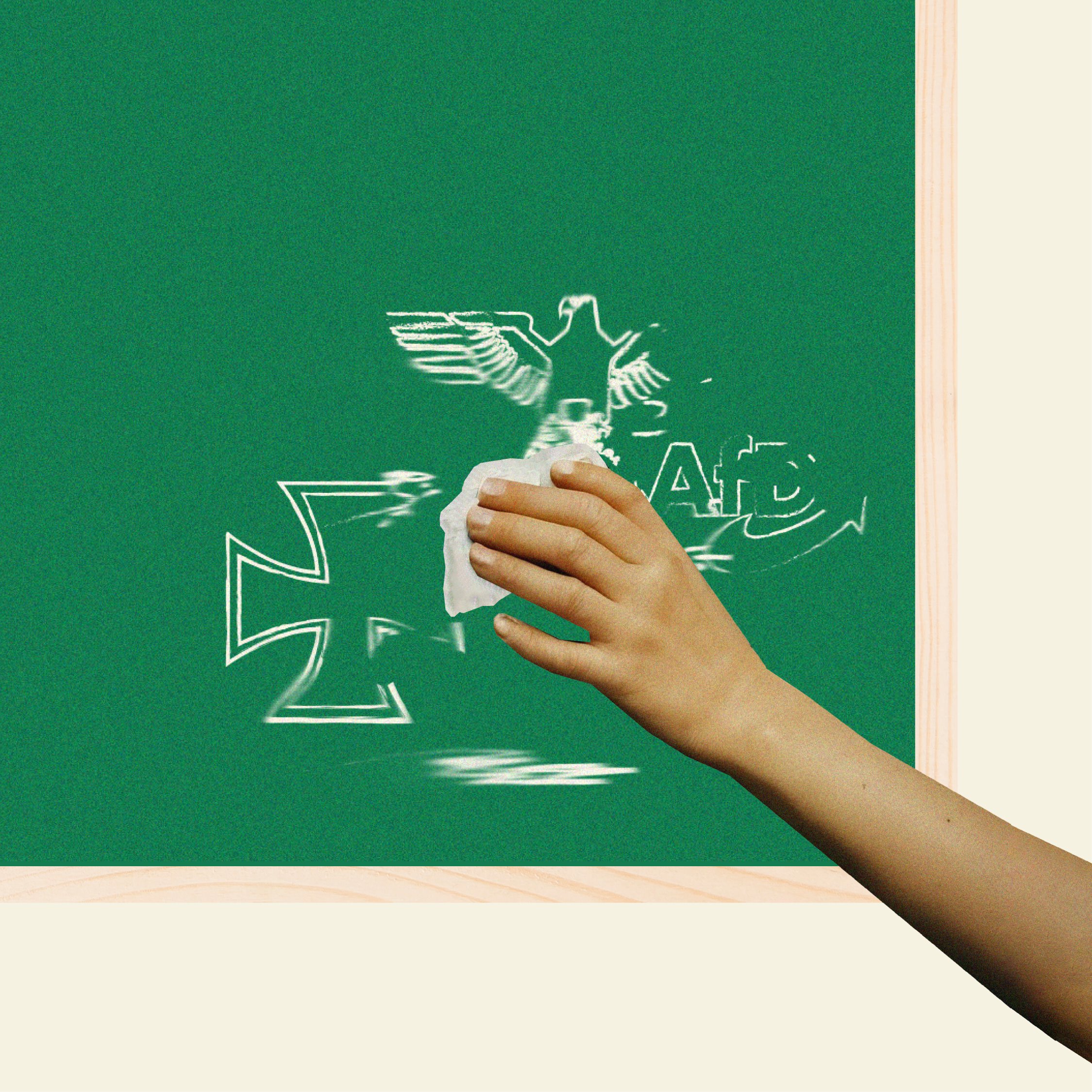

The war in Gaza comes at a moment when every major political party in Germany is lurching rightward on the issue of migration, embracing xenophobic and Islamophobic policies once reserved for the marginalized far right. “Germany cannot accept any more refugees,” Friedrich Merz, the leader of the Christian Democratic Union, the party of Merkel, said. “We have enough antisemitic men in this country.” Scholz, a Social Democrat, appeared on the cover of Der Spiegel in a determined portrait framed by the quote: “We must finally deport on a grand scale.” The specter of antisemitism has proved opportune for mainstream parties, which are threatened by a surge in popularity for the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD, whose platform is proudly anti-immigrant.

In a much-publicized speech on November 2, Vice-chancellor Robert Habeck, a member of the left-leaning Green Party, lamented that several Jews in Germany had told him they felt afraid to display their Jewishness or even appear in public. Habeck blamed unspecified Muslim groups for being “too hesitant” to condemn Hamas. He pointed to Germany’s historic need to defend Israel. “Too much seems to me to have been mixed up too quickly,” he said. “It was the generation of my grandparents that wanted to exterminate Jewish life in Germany and Europe.” He continued with the standard German conflation: “After the Holocaust, the founding of Israel was the promise of protection to the Jews — and Germany is compelled to help ensure that this promise can be fulfilled.” The connection between the founding of Israel and the failings of Germany’s Muslims was clear; Habeck denounced as “unacceptable” the scale of the “Islamist demonstrations” in Germany. “Muslims living here,” he went on, “must clearly distance themselves from antisemitism so as not to undermine their own right to tolerance.” The constitutional rights of Muslims, it seems, are contingent on their approval of Germany’s unique form of anti-antisemitism.

A few days ago, in a move that is hard to read as anything other than a provocation intended to incite protest and “emotionalize” locals, bus stops around Neukölln were adorned with government posters depicting the flag of Israel waving before the Bundestag. The posters read: “Solidarity with Israel.” The German state has indeed continued to stand with Israel, most recently by authorizing arms exports to its Staatsraison ally totaling 300 million euros, nearly a tenfold increase over 2022.

Just as reports of attacks on mosques have risen since October 7, recent incidents of antisemitic crimes have produced fear among Jews in Germany. Stars of David have been painted outside Jewish homes; a synagogue in Berlin was firebombed, albeit with no injuries or property damage. These are not isolated events; the number of antisemitic incidents in 2021 was the highest since authorities began tracking them. Yet politicians’ focus on Muslims and migrants as their source runs contrary to the facts. According to the federal police, the “vast majority” of antisemitic crimes – more than 80 percent — are committed by the far right.