The Trial of Poland’s “Abortion Dream Team”

Polish activist Justyna Wydrzyńska faces up to three years in prison for providing abortion pills to a pregnant woman.

JANUARY 25, 2023

The Warsaw District Court is an angular concrete-and-glass building on Poligonowa Street, a name that means “military training ground” or “firing range.” On the morning of January 11, a few dozen people milled around in front of the court. They had come to support Justyna Wydrzyńska, an abortion-rights activist who has been on trial for the past year for providing abortion pills. They banged drums and yelled chants in solidarity with her cause. On the other side of the street, a handful of anti-abortion protestors tried to drown them out by reciting prayers for unborn children over a loudspeaker. A line of police officers stood between the two groups. Reinforcements waited in parked squad cars nearby.

Wydrzyńska is a member of a collective of Polish women known as the Abortion Dream Team. Over the past seven years, they made it their mission to help women secure pregnancy terminations in Poland, where the process is almost entirely illegal. Between October 2021 and October 2022, the Abortion Dream Team reportedly helped some 44,000 women in Poland secure abortions, according to data on the organization’s website. The previous year, they reported helping 34,000 women secure terminations.

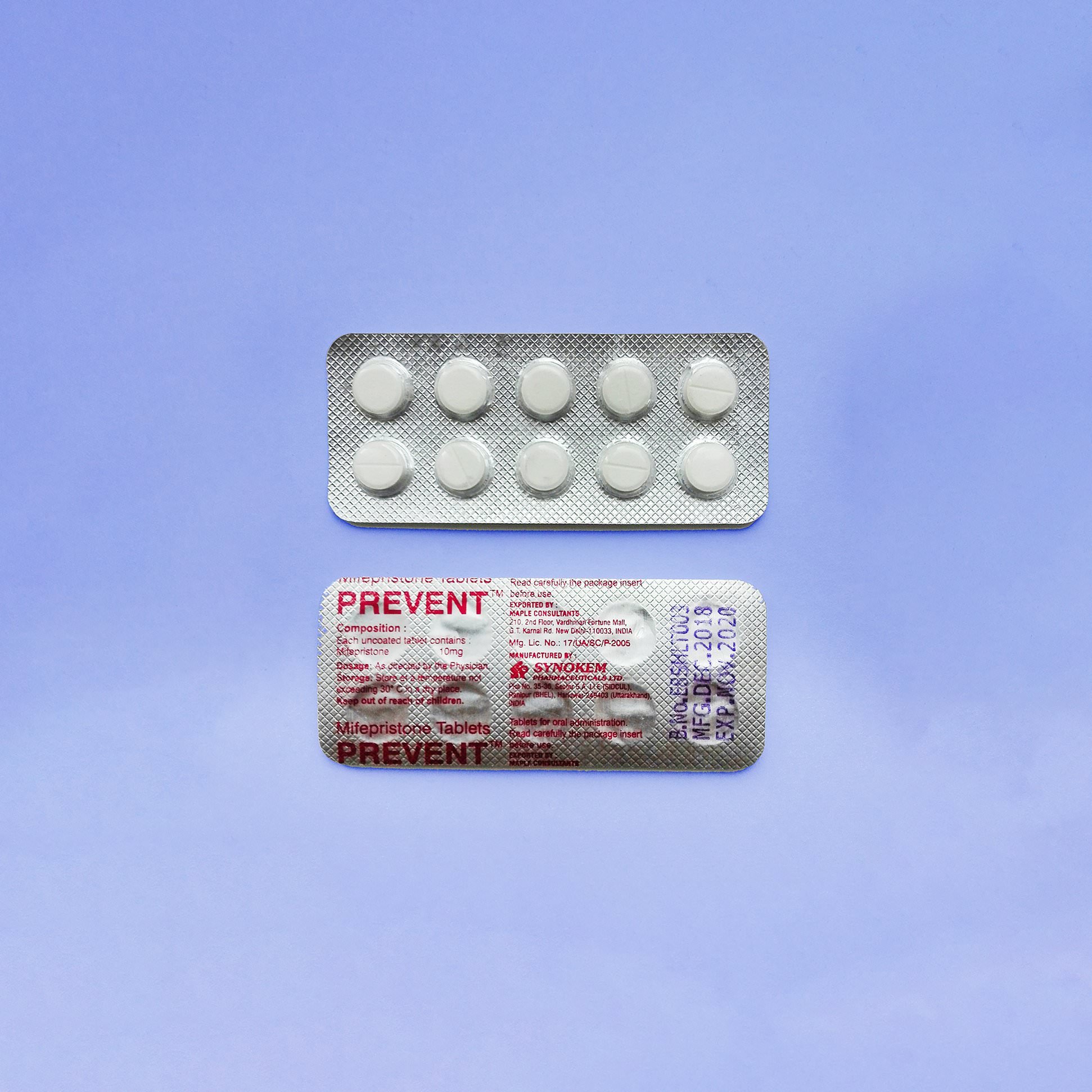

Today, Wydrzyńska faces up to three years in prison for providing abortion pills to a pregnant woman in 2020. Early that year, at the beginning of the pandemic, the Abortion Dream Team was contacted by a woman named Ania who was 12 weeks pregnant. Ania told the Dream Team that she had hoped to travel abroad to secure an abortion, but her husband forced her to stay in Poland. As a result, Ania requested and received abortion pills from Wydrzyńska. When Ania’s husband discovered the pills, he informed the police.

The hearing on Jan. 11 took place in a medium-size courtroom packed to the brim with reporters, photographers, and camera equipment. Much of the equipment was superfluous because recording or broadcasting the interrogation of the key witness that day — Ania’s husband — was forbidden. He had previously been fined for repeatedly failing to appear in court, so, in a sense, his presence marked an advancement in the proceedings. (His identity is protected under Polish privacy law.) After hearing his testimony while reporters waited outside, the judge requested police files pertaining to domestic violence in his household. His wife, Ania, was not present in court that day. The judge cited a sick note from a doctor that explained her absence.

For the past several decades, abortion laws have been progressively tightened in Poland. In 1993, a law that is often referred to as the Polish “abortion compromise” went into force. It allowed for abortion under only three circumstances: first, if the pregnancy threatened the life or health of the mother; second, if it was the result of a criminal assault; and third, if serious fetal defects were detected.

In 2020, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal introduced a near-total abortion ban, stripping the right to termination for “embryo-pathological reasons.” It effectively outlawed over 90% of about 1,000 terminations conducted in Poland annually. As a result, Poland now has some of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe. (Malta is the only EU nation with more restrictive laws — there, abortion is illegal in all cases.) Wydrzyńska stands accused of violating Article 152 of the Polish penal code, which forbids both “conducting an unlawful termination of a pregnancy” and “helping” or “encouraging such termination.” The prohibition carries a potential sentence of up to three years in prison. The sentence can be extended for up to eight years if the violation takes place after the “conceived child” has already reached a stage of development that would allow “for independent life outside the body of the pregnant woman.” In Poland, that stage is considered to be 22 weeks’ gestation.

According to Polish law, only the person who conducts an abortion or helps an individual to secure one is criminally liable. Any woman who receives an abortion is totally safe, as far as the law is concerned. “Yet now, some might feel that they will end up being dragged to court as witnesses and forced to give testimonies,” said Magdalena Biejat, an opposition MP who has advocated for women’s rights.

The trial first opened in Warsaw on April 8, 2022. That morning outside the court on Poligonowa, two demonstrations took place, as they would every time there was a hearing on Wydrzyńska’s case. Supporters of the Abortion Dream Team lined one side of the street holding signs that read, “Honor and glory to abortion activists,” “Abortion saves lives” and “I have pills and I won’t hesitate to use them!” On the other side stood a van bearing an enlarged image of an aborted fetus and the slogan “Abortion Pill Kills.” In the road between them there were lots of police, their mouths and noses covered with black scarves. They would become as much of a presence at the trial as the lawyers and activists.

“I am an abortion activist,” Wydrzyńska declared at that first court hearing. “When I heard the story of this person, I realized I didn’t have any choice,” she said:

I made a spontaneous decision, since I had the pills for myself. … I realized that I have to help this person, as I understand what she’s going through. … I know abuse and I know its symptoms.

The Ordo Iuris Institute for Legal Culture, an ultraconservative group known for speaking out against LGBTQ rights and sex education and in favor of fetal personhood, was granted the status of a “social representative” in Wydrzyńska’s trial, meaning that the organization has the right to submit a written statement to the court and to present its opinion during closing arguments. The group has been especially vocal in anti-abortion campaigns and has encouraged Polish prosecutors to pursue cases against anyone who advertises or provides what it refers to as “death pills” to terminate pregnancies.

“This crime has no victim. The aggrieved are only conservative values of those who created those laws.”

In its written statement submitted to the court in July, the organization argued that in Poland “unborn children … have full constitutional subjectivity,” and that the “protection of their life through Article 152 is the realization of constitutional norms.”

Biejat, the opposition MP, sat beside her colleague Katarzyna Kotula in the hearing room in October. “We come to court session as representatives of the Left [Lewica] party as we want to show our support for Justyna and all the members of the Abortion Dream Team,” Biejat said. She sees the trial as a potential turning point for the decriminalization of reproductive rights in Poland because the court has the power to “significantly influence the way women will receive help [with terminations] in the coming months, if not years.”

✺

Over the last 20 years, the number of abortion-rights prosecutions has steadily increased in Poland. In 2002, two individuals were convicted of violating the same article of the penal code for which Wydrzyńska stands accused. In 2003, three people were convicted; 22 were sentenced in 2008; 26 in 2018. In 2021, prosecutors were investigating 240 cases relating to Article 152. “This crime has no victim,” said Kamila Ferenc, a lawyer from the Foundation for Women and Family Planning (Federa). “The aggrieved are only the conservative values of those who created those laws.”

In 2000, a woman named Alicja Tysiąc went almost completely blind after she was refused the right to terminate her pregnancy. Her doctors told her that the pregnancy would worsen her eye disease, but she was forced to give birth all the same. She had looked into securing a backstreet abortion but said in an interview that she would have had to pay 5,000 złoty (about $1,150) for the procedure, which she simply couldn’t afford. She sued the Polish state.

In 2007, following years of court battles, the European Court of Human Rights recognized that Tysiąc was wronged and granted her non-pecuniary damages. But by that time her eyesight had almost completely deteriorated. She was supporting three children with her disability pension and had been forced to organize crowdfunding campaigns to pay for medical care.

Another Polish woman — a 30-year-old known only as Izabela, from the small town of Pszczyna — died of septic shock in September 2021. According to her mother and Jolanta Budzowska, the lawyer now representing her case, Izabela’s condition rapidly deteriorated in the hospital, but her doctors waited for her fetus’s heartbeat to stop before they performed the cesarean section that could have saved her life. From her hospital bed, Izabela communicated with her mother via text message: “For now, thanks to the abortion law, I have to lie here, there’s nothing they can do,” she wrote. After her death, tens of thousands took to the streets in protest across Poland. In Warsaw, some 25,000 marched to the Ministry of Health and held their cellphone flashlights aloft in the night sky.

Anyone who has lent aid to an woman seeking an abortion—be they family members, friends, partners, or husbands, sometimes even bus drivers—is forced to contend with the possible consequences of violating the law.

Izabela’s two doctors were suspended from their hospital and charged with “professional negligence” in September 2022. Their case is still ongoing.

Data from the Institute of Justice, the analytical think tank of the Ministry of Justice, reveals that judges’ responses to violations of abortion laws varied. Out of 26 convictions in 2018, fines of up to 1,000 złoty were imposed in three cases. Six were sentenced to limited freedom of movement for up to two years. Seventeen received up to a year’s imprisonment, though a great majority of them (15) were suspended sentences.

Anyone who has lent aid to a woman seeking an abortion — be they family members, friends, partners or husbands, sometimes even bus drivers — is forced to contend with the possible consequences of violating the law.

As a result of the 2020 abortion ban, abortion-rights organizations started providing financial, logistical and psychological support for both self-administered terminations and abortions abroad, putting activists in greater danger of prosecution. According to Federa, the largest Polish women’s rights organization, the underground market for abortion pills has gradually made unlicensed abortion clinics obsolete in Poland. Women seeking terminations rely on activist groups like the Abortion Dream Team, who openly advertise their support online and on social media channels.

To date, over 1,200 women have relied on the Dream Team’s support to organize late abortions conducted in Western European medical facilities, many of them in the Netherlands. About 40% of women who reached out to Dream Team in the second trimester of their pregnancies had received a diagnosis of defect in the fetus. According to the Dream Team’s estimates, between three and six Polish women terminate their pregnancies in Dutch clinics every day. Femke van Straaten, the head of a Dutch abortion clinic, reported that approximately 1,300 Polish women have had abortions in the Netherlands over the last two years. “Since 2021 we were flooded with women traveling from Poland seeking abortion care,” van Straaten said during a special hearing organized in the Sejm, the lower house of the Polish parliament. The majority of the women had decided on termination due to medical reasons, she said, and had been forced to seek care outside of Poland.

✺

Wydrzyńska’s next court hearings are scheduled for Feb. 6 and March 14.

“It can go very different ways now — either a very strict sentence will be passed to make an exemplary showcase of it,” said Ferenc, the women’s rights lawyer, “or the punishment won’t be severe at all and in the verdict explanation the judge will express her understanding for Justyna’s motive and recognize that she wanted to help.”

Biejat, however, sees the chilling effect striking elsewhere. “The doctor will be even more reluctant to take responsibility for the life and health of their patients,” she said, while pregnant women considering termination, and their families, “might be terrified that support and help will mean that a prosecutor arrives at their doorstep one day.”

While Wydrzyńska’s trial is ongoing, the Foundation for Life and Family, another ultraconservative Polish group, is attempting to target the supply, distribution and advertisement of self-administered abortion pills. In the latest draft law submitted to the Parliament as citizens’ initiative, the group demands even further tightening of the abortion law, seeking to criminalize the very act of providing basic information on abortions. (A state spokesperson has since said the government will not support the bill, but this does not mean it won’t be discussed in Parliament or gain support).

Nothing summarizes the dominating attitude in Poland’s ruling camp better than the words of Jarosław Kaczyński, chairman of the ruling Law and Justice party (known as PiS), soon after the introduction of the near-total ban. “In my opinion nothing that would threaten women’s interests has happened,” he said. “I don’t accept the right to abortion as a principle — it’s evil.”

In some parts of Poland, students are offered extra credit for participating in contests in which they are asked to produce artistic content related to a number of themes, one of which is “opposing abortion.” The contest organizers boast that one entry — a short film produced by teenagers in 2015 — has dissuaded women with unwanted pregnancies from seeking termination.

✺ Published in “Issue 1: Egg” of The Dial

PHOTO: Jaap Arriens/NurPhoto via AP