Reporting from Exile

Journalists forced out of their home countries reflect on how displacement has affected their work.

OCTOBER 31, 2023

Today, hundreds of journalists are forced to live and work in exile from their home countries. While the specific reasons they have been forced into exile vary, they are all ultimately rooted in the global upswing in repression against independent media, and the chilling of free speech world wide. These reporters continue to cover their nations from far away, relying upon cellular and internet communications to do their work, as well as upon networks of local informers who can take great risks to relay first-hand information. Some of the best reporting that you've read in the past year was conducted hundreds miles from where the events took place, and across a political border.

At The Dial, we often work with exiled journalists, many of whom report in languages other than English, to publish their work. In this roundtable, we asked five journalists to tell us about how they have navigated the conditions of exile, and how they report on countries they can no longer see.

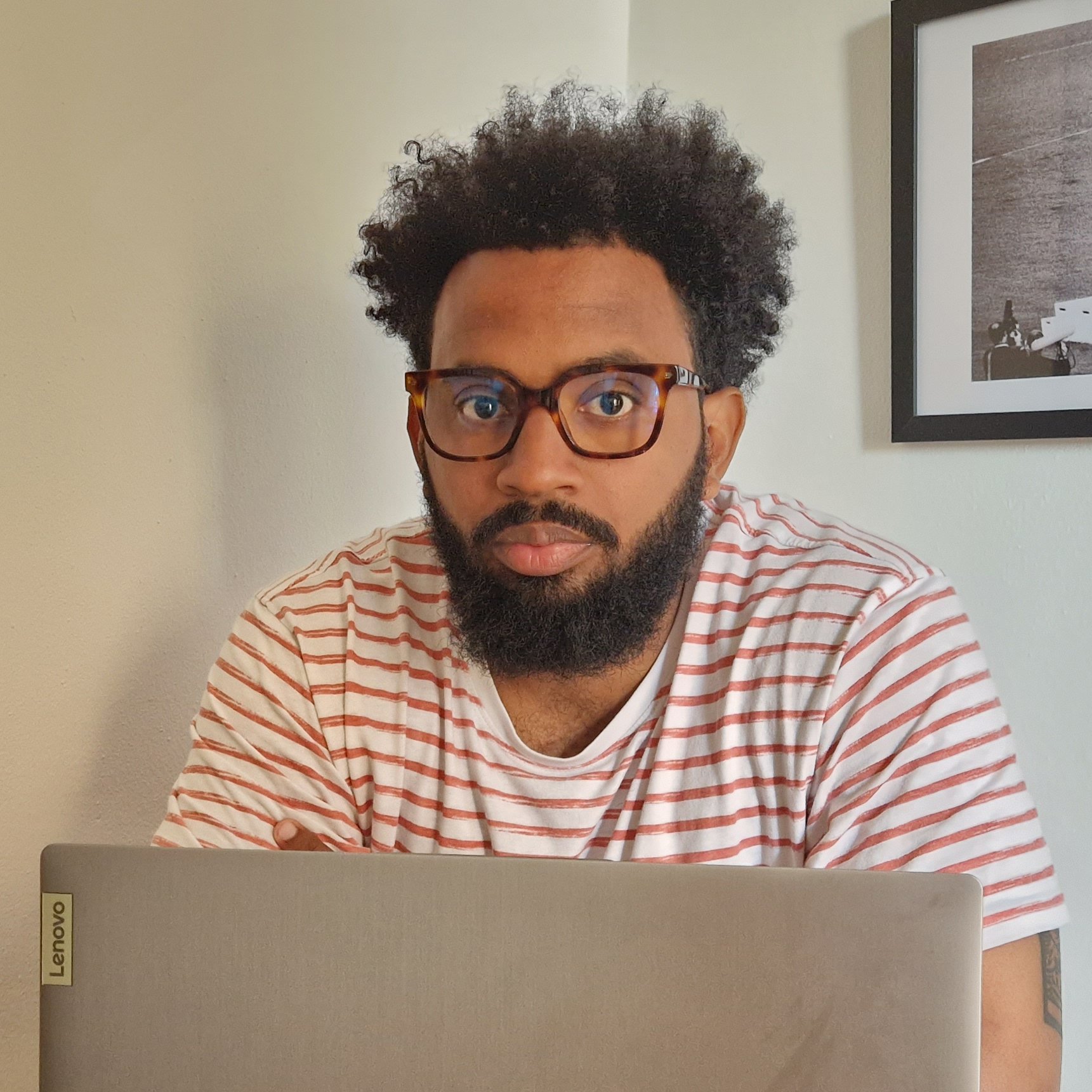

Abraham Jiménez Enoa

Cuba → Spain

Abraham Jiménez Enoa is a Cuban journalist and co-founder of El Estornudo, Cuba’s first independent magazine of narrative journalism. In 2021, after years of harassing Jiménez for his coverage, Cuban authorities threatened to imprison him. He fled to Spain. From Barcelona, where he now lives with his wife and son, Enoa still reports on Cuba, runs El Estorwnudo, and writes columns for The Washington Post. Last year, he published La Isla Oculta, the product of years of immersive reporting in Cuba, from exile. An excerpt of the book was published in The Dial. This interview was conducted by Nicole Dirks and translated by Jessica Sequeira.

✺

How do you report now from exile? Are sources eager to talk? How do you choose what stories to pursue from Spain?

To report from exile is now much more difficult. Not because it’s hard to find sources of information from far away, but because it’s much more complicated to check up on what they tell you. In journalism, to write a line you have to be sure that it’s true, and if you aren’t in the place and something has been left out of the story, you have to verify it. That is the difficult part now. Not being in the place where events happen complicates the work for us, and makes us put in double the effort to confirm the information that we obtain.

The sources still have the same desire to speak. There are very few media outlets, and very few Cuban journalists who care about speaking about the reality of the country. So people keep talking to the few of us who do that, even if we’re an ocean of distance away. We’re the only ones willing to expose what’s happening in the country.

How and why did you first come to edit El Estornudo (The Sneeze)? What’s it like running it now from exile? How do you communicate from Spain with journalists writing for the publication?

My colleagues and I founded El Estornudo because we wanted to talk about the real Cuba, and didn’t have a place to do that. We’d left university, and there were no media outlets that offered a space to do the kind of journalism we wanted. In Cuba, there is a single political party, the communist party. And by law, that party is the one that directs all media. All of the radio stations, all of the television channels, all of the magazines and all of the newspapers are subordinated to the communist party. And to do journalism outside that legal umbrella is to break the law, it makes you a criminal. For that reason we founded El Estornudo, which became an illegal magazine.

My daily life was kidnappings, arbitrary detentions in prisons, interrogations, house arrests, interventions in my private communication. I was under surveillance wherever I went.

I was the director of the magazine for the first four years, from 2016 to 2020, but then left it. The majority of my colleagues had gone into exile, and I was one of the few who remained in Cuba. Working that way became very complicated.

What was your life like reporting in Cuba? And to the extent you’re comfortable with sharing, what were the conditions that made you leave?

It was an unbearable life. As time went by, I was left without oxygen. My daily life was kidnappings, arbitrary detentions in prisons, interrogations, house arrests, interventions in my private communication. I was under surveillance wherever I went. My friends and family members were also pursued and interrogated, and taken to jail cells. My parents and one of my sisters lost their jobs as retaliation for the journalism that I did. Another one of the measures the government took against me, to force my silence, was to prevent me from leaving the country. They didn’t let me have a passport, and I was shut away in the island without being able to leave it, living in a kind of political prison. For that reason, when the country exploded and people went out to the streets in mass protest, in the summer of 2021, the government decided to give me a call. I was one of the few journalists who narrated those protests from the inside. In that telephone call, they told me that they’d grant me my passport so that I’d leave the country, and if I didn’t they’d lock me up. They offered me exile or jail to finally get rid of me. Obviously I chose exile. That’s why I’m here now and can’t return.

You recently published “La revolución de los acuáticos” (The Revolution of the Water Believers), the first chapter from your book La isla oculta (The Hidden Island), in our Drugs issue. I understand that you did your reporting for the book from Cuba but published it from Spain. How did you do research for “La revolución de los acuáticos”? How do you see the story now? How has the book been received in Cuba?

All the stories in the La isla oculta, save for the epilogue, were written in Cuba. The story of the “acuáticos” [water believers, Cubans suspicious of doctors who instead believe in the healing powers of water] is one that I’ve always wanted to tell. It’s one of those stories that sound like fiction when you hear it. For that same reason, it’s always attracted me and I wanted to go meet those people. I went to the mountains [in the Cuban provinces of Pinar del Río and Artemisa] and spent several weeks living with those characters. It was the only way to be able to understand their lives. Now that time has gone by, I feel proud to have told it, since many people learned about the existence of those people thanks to the book. I don’t have a very clear idea of the reception of the book in Cuba, because the government won’t allow it to be edited or distributed. Those who have read it within Cuba got hold of it there from abroad. But the positive reception that it’s had with Cuban exiles makes me very happy. Many, many Cubans have written me from many, many countries. We Cubans are scattered all over the world.

You wrote about the stressful early days of your arrival in Spain, in the moving epilogue to your book. Have you settled in more now? Do you feel safe? How do you handle leading such a public life?

That was the first time I’d ever left Cuba. I’d never experienced another reality that wasn’t Cuban, and landing up in a new place was very hard. That’s why I added that epilogue to my book. And that’s why the book I’m writing now, my second one, narrates in depth my first year outside Cuba, and the motivations for that exile. I feel more adapted now, but I’m still not safe. The Cuban government keeps harassing me. There have already been three actions taken in three different cities, Amsterdam, Madrid and Barcelona, where people have reprimanded me, filmed me, threatened me. The only way I have to defend and take care of myself is to publicly denounce each of those actions. Although increasingly, I try to go unnoticed. I’m at a moment in my life when I have to distance myself from the racket.

What would need to change in Cuba for you to go back?

I want to live in Cuba, not abroad. I live in exile because I was forced into it. For the moment, I can’t go back because the government of my country prevents it. The government must collapse before I can return and be in my land.

Ayham Al Sati

Syria → Spain

Ayham al Sati, a journalist from Syria, had to leave his country like many others in 2018. Upon his arrival in Spain, he realized that there was a strong Arab community struggling to figure out the immigration process— that’s when he and other refugee journalists decided to found Baynana, a Spanish-Arabic news outlet dedicated to building bridges between the migrant community in Spain and sharing valuable information to them. As told to Lucía Cholakian Herrera.

✺

I started my career as a journalist unexpectedly in Syria. By participating in demonstrations against the Syrian regime, I started recording videos and writing news about these events. Living in a country without freedom of the press, we, the youth, became voices of truth. I was jailed twice before I had to leave my country due to the increasing threat to my life.

In 2018, I had to leave my area in southern Syria due to an agreement between the Syrian regime and the opposition. The situation was dangerous and I knew my life was at risk. I made the difficult decision to leave the country in just 24 hours, together with my family. First we went to Turkey, and then I came to Spain. I was contacted by the Committee to Protect Journalists, who offered me the possibility to leave Syria and reach Europe, specifically Spain. I had no other option, I needed to leave my country.

However, when I arrived in Spain, I did not imagine that I was going to work in journalism. I couldn't even say “hello” in Spanish at that time. I started learning Spanish from day one. We were a group of four refugee journalists facing practical challenges like getting a digital certificate and scheduling appointments to apply for asylum. Everything was in Spanish and we felt a pressing need to understand the system. We realized we had to do something for our Arab and immigrant community here.

Our passion for telling the real and authentic stories of migrants and refugees in Spain drives us forward.

We had founded local media in Syria to cover the war, so the idea of establishing a media outlet in Spain to address migration and raise awareness of Arab countries resonated with us. Despite our connection to Syria, our main goal with Baynana was to create a platform for the immigrant community in Spain. Fortunately, we had the support of the PorCausa Foundation, who were our friends from the beginning of our journey in Spain. They work on migration research. They supported us by offering us a space in their office, and also with contacts.

Baynana is a bilingual magazine in Arabic and Spanish, founded by Syrian refugee journalists. Our goal with Baynana was to offer useful and quality information for the Arab and migrant community in Spain and at the same time to weave links between migrants, refugees and Spanish people of foreign origin, and the rest of the population. I learn a lot from the experience: the most important thing being patience, as we work differently from most media, focusing on variety and quality, which takes time. Our reporting is always in-depth and we spend time researching and telling detailed stories. We faced significant challenges, especially in language and fundraising. The Spanish language was an initial hurdle, and the lack of representation of refugee voices in the Spanish media motivated us to document our own experiences and provide a platform for others to share their stories.

Over time, we have learned to adapt and overcome obstacles, we have managed to learn Spanish at the speaking and writing level. Our passion for telling the real and authentic stories of migrants and refugees in Spain drives us forward. Despite the challenges, we are committed to contributing to a more inclusive and understanding society through our work.

Tamerat Negera

Ethiopia → Washington, D.C.

In 2018, Tamerat Negera, an Ethiopian journalist who had been living in exile, returned to Ethiopia. Abiy Ahmed, a former soldier and military intelligence officer, had recently been named prime minister and promised to alleviate tensions between the country’s largest ethnic groups. Ahmed brokered peace with Eritrea within four months, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize. But when the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which had ruled the country for most of the prior three decades, attacked a military base in November 2020, a civil war ensued and Abiy’s troops massacred both TPLF members and civilians; other ethnic militias mobilized and followed suit. By August 2023, nearly 3 million Ethiopians were displaced by conflict and an estimated 600,000 people, the vast majority civilians, had been killed.

Negera reported critically of the war and of Abiy’s leadership, and in December 2021, Abiy’s federal police kidnapped Negera and brought him to a military black site. Accused of ‘humiliating and insulting regional and national leaders,’ of ‘instigating unrest,’ even ‘terrorizing the nation’ through his writing, Negera was never charged and spent four months in detention. After his release, in April 2022, he fled into exile once again. Forced to shut his news company down, he hosts a political talk show on Youtube. As told to Jacob Kushner.

✺

When Abiy assumed power, he was not a very famous person. He’d been active in Ethiopia’s military intelligence service, blocking websites and hacking cellular networks of dissident journalists and political opponents — suppressing dissent and independent views. Once he came to power he said, we’ve tried this approach. He changed things with unbelievable speed: releasing political prisoners, unblocking websites, releasing journalists. To exiled journalists like us, it was shocking. I used to be the editor of a newspaper, Addis Neger. Abiy sent a message to our columnist who was part of his transition team: Your newspaper was my favorite, it’s very sad what happened. The state will do anything to facilitate your return. Our politics have been dominated by baby boomers, so we were like, ‘this is our guy!’

One year after the war started, in December 2021, I was taken from my home by federal police. They searched my home and confiscated $15,000 in equipment from my office. They cleaned us out.

Hindsight is 20/20. When I went back to Ethiopia, Abiy’s administration was already showing cracks — inability to secure the country, basic security. Blocking websites became normal — shutting down internet when there was even just a little bit of conflict. But small conflicts in a big population country like ours can cost hundreds of lives.

When the TPLF attacked the northern army base…that was a saving grace for Abiy. People have a deep hatred for the TPLF regime. They’d been ruling for 20 years. We know what they did to the country. Most people supported Abiy’s war.

Journalists like me started criticizing how things were being handled on the ground — the human rights abuses, the massacres in Amhara, in Afar…the involvement of Eritreans. The government declared a very broad state of emergency, using the war as an excuse. Abiy hired teams of people to go on Facebook and challenge our comments, trying to control the online discussion. Facebook blocked many fake accounts belonging to the government.

One year after the war started, in December 2021, I was taken from my home by federal police. They searched my home and confiscated $15,000 in equipment from my office. They cleaned us out.

I was taken to a black site. For seven days they didn’t tell my wife where. During the interrogation they asked, do you know why we brought you here? They said you are working with TPLF. My whole life I have been fighting against TPLF as a journalist. They didn’t charge me or close the case, they just released me on bail — suspended it so that I couldn’t speak. The possibility of returning to prison was real.

People warned me not to try to get visa to Western country because security agents were watching the embassies. So I went to Thailand for medical treatment with my wife. Thank God I was not caught at the airport. From Thailand, the National Press Club invited me to an event in Washington D.C. That’s how I came back here.

Western journalists get trapped in just three sources of information: civil society NGOs; aid organizations; and Western academics. Most of you do not speak, read, or understand a single African language. Can you imagine me having a PhD on American politics without knowing the English language? Would you reach out to me and consider me an expert on American politics? There is this attempt to be on the side of the victim, but while a community can sound like the victim, it’s a thousand-year-old conflict. It didn’t just start in 2020. You have to understand the context.

We journalists like narratives. We love to build and we love to destroy. Abiy gets to be labeled a Nobel, and then a war hero. That’s a universal failure: we love to build heroes, and we also like to crush them.

How do we escape that? One way is long-form stories. There was fantastic work by New Yorker journalist Jon Lee Anderson, who spent time with Abiy. Anderson let him talk, let him skewer himself. Abiy is so obsessed with his image, his Nobel, his intelligence. He is building a cult about himself. But individuals are also products of systems. When we focus on a person, we lose focus on the system that people are living under. For the evil that’s happening in Ethiopia, you can’t just blame the leader.

Abiy continues to detain journalists who are critical of the war. We’re at a point where you have to leave the country just to survive. I said to my team, I can’t afford to see you being arrested, while I’m outside. I shut down the company. I have some friends that are very brave and are trying to continue working. The Addis Standard is doing good reporting, but they’re pro OLF-OLA (the main political party of the Oromo, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group). Borkena adheres to no particular ethnic affiliation and is also doing important work. The Reporter is pro-TPLF and has been producing great reporting for years. But the police are hiring thieves to rob media organizations and make sure they are unable to work. Nowadays I ask my friends: are you planning to leave the country? Or are you shutting down your media outlet and being quiet?

—

In exile, Negera recently re-started the Terara Network on Youtube. Abiy Ahmed’s office did not reply to requests for an interview.

Saw Chit Aye

Myanmar → Thai border

Myanmar’s only local media outlet focusing on the ethnic Karenni minority, the Kantarawaddy Times relocated from the town of Demoso in Karenni State, to an undisclosed location on the border with Thailand in June of 2021 due to escalating armed conflict between the military and local resistance forces opposing its February 2021 coup. Renamed Kayah State in 1989 as part of the military’s efforts to reassign place names given by British colonial authorities, Karenni State has been wracked by intense violence since armed resistance to the coup erupted in May of 2021. As in other parts of the country, the military has retaliated against armed resistance in Karenni with airstrikes, artillery fire and arson. According to the United Nations, the violence has displaced more than 100,000 people in Karenni State out of 1.7 million people internally displaced across the country. With the military attacking displacement camps and blocking humanitarian access, many people from Karenni have also fled across the country’s southeastern border with Thailand, where they lack formal recognition or legal protection as refugees.

The Kantarawaddy Times has been documenting these developments through a combination of on-the-ground and remote reporting, offering a vital window into the ongoing armed conflict and humanitarian crisis. In December of 2021, it also covered the military’s Christmas Eve massacre of more than 35 civilians including women and children. Its reporting has been referenced by rights documentation groups including Myanmar Witness and Amnesty International and media outlets including The New York Times.

Saw Chit Aye, the editor-in-chief, spoke with Emily Fishbein. This interview, translated from Burmese by Zau Myet Awng, has been edited for length and clarity.

✺

When the coup happened, we were a team of five people working out of an office in Demoso. We stopped going to the office not long after, because the military was arresting journalists across the country. When the war broke out in May of 2021, we couldn’t work from home anymore either. Phone and internet connections were unreliable and the military was indiscriminately bombing and shelling civilian areas.

By June of 2021, more than 100,000 people had been displaced across Karenni State, including me and my colleagues. We walked through the jungle for four days until we reached the Thailand border.

Before the coup, we mainly covered the local economy and Karenni social and cultural issues, but suddenly, we were looking at graphic and violent images daily and covering severe human rights abuses including the massacre of civilians.

We resumed our operations around three months later, and have since expanded our team to around 25 people. In addition to our daily news coverage, we host a radio show in Karenni and Burmese, where we cover the conflict between local resistance forces and the military as well as the humanitarian crisis.

This work has affected us psychologically. Before the coup, we mainly covered the local economy and Karenni social and cultural issues, but suddenly, we were looking at graphic and violent images daily and covering severe human rights abuses including the massacre of civilians. We were so sad and traumatized and sometimes, it was really hard to get through each day.

Now it has been more than two years, so we have become conditioned, but some things still really affect us. For example, one of my colleagues covered an airstrike in an area where her family was also staying. We really empathized with her.

When reporting on the ground, we also face the same risks as other civilians. If the military attacks the village or camp where we are staying, we are in danger too. Covering the conflict is difficult as well. Phone and internet connections are limited outside of the state capital of Loikaw, and we also have some challenges collecting information from resistance groups. When we try to cover a battle that doesn’t look good for them, they sometimes decline interview requests or suggest that it would be better if we didn’t write about it. And because it’s not safe to travel alone, sometimes our journalists have to travel together with resistance groups. This can increase the pressure we feel to cover a story in a certain way, out of a sense of obligation.

As for me, I haven’t been back to my hometown since May of 2021. It is deserted because of the fighting and landmine risks. Luckily, I fled here with my family. Some journalists can only get in touch with their families once in a while because of internet and phone connectivity issues.

Alongside my work as a journalist, I am doing what I can to help my community. Sometimes, my colleagues and I donate our advertising revenue to a local humanitarian committee, and we have allocated a percentage of our salaries to them as well. We also help them to connect with local resources so that they can deliver food and relief supplies to people in need.

My colleagues and I are all in our 20s and 30s. We are young and enthusiastic, and we are trying our best. We are the only Karenni media outlet; there is no one to take our place if we stop. So I feel that it is our responsibility to keep going and keep trying.

Annie Zhang

Hong Kong → Taiwan

Annie Zhang, former editor-in-chief of Initium Media, left Hong Kong for Taiwan in 2018 in “self-exile,” before exile could be imposed on her. After moving, she started a social media platform and works as a columnist for Chinese media, mainly focused on diaspora communities. Zhang is not sure she can or will ever go back. As told to Alex W. Palmer.

✺

I know some friends who are certainly in exile because they were arrested on the mainland. After being released they chose to leave and don’t plan to go back. For me, it’s more like a self-exile — before it could be imposed, I chose to leave. I unwittingly left Hong Kong in 2018 and now I’m not sure if I will or can go back. The situation is not clear. A lot of my friends, sometimes including me, will say that we are reporting on global China or are trying to build communities in the diaspora — change the idea of exile to a positive, to gain some feeling of autonomy rather than being forced out.

Hong Kong is the signal — it’s not the end, it’s the beginning of the changes coming in Chinese history. The city is the bridge between China and the world, and if China and the world need this bridge, it will exist. If the world and China don’t need it anymore, it will collapse. That’s what we saw in 2019. Of course, even before then the situation was not good and became worse and worse as time went on, but still I could go back to China while living in Hong Kong. But after 2019, the national security law, and after COVID, everything changed. It did not happen all of a sudden, but it’s become much worse than before.

We can still keep very close connection with people inside China, through the internet, Twitter, WeChat. Of course it’s hard to discuss politically sensitive things, but normal things like daily life and general economic situation – your salaries, your work – we can continue those connections. Those are very important.

The so-called Chinese diaspora community has a long history, and more than 80 million members. This part of the story has so much potential. For journalists we still have so much to do.

After 2018, when I left Hong Kong initially, I started my own company, a social media platform. I’m a columnist for Chinese media and I still write about China, but my stories are mainly focused on so-called “global China” and diaspora communities. I chose not to go back to China to avoid the entire question of security. If you have to go inside and outside China, to go between China and the world, you have to maintain the highest level of personal security. But if you don’t, you can live a normal life. I chose not to go back, to physically unplug from China. If I go back, I know that many of my friends are in trouble on the mainland. Some secret police will ask me a lot of questions, either about myself or my friends. I don’t want to put myself in that situation – to put myself at risk or make myself a source for the policeman.

My focus became figuring out how to mobilize these people — how to build community in a decentralized manner. Can we still build an alternative Chinese society in a free, peaceful, autonomous way?

They’re collecting information everywhere. But they’re not collecting it for truth, but for repression. I don’t talk with my parents about the things I experience now. They don’t know I opened a bookstore or even that I have lived in Taiwan for three years. Because we talk on WeChat, I can’t say much and don’t want to leave a record.

The media ecosystem in China is part of the political ecosystem. I do think we are still at the very beginning of the long-term downward slope of history. I don’t think the question is whether war will come or not, because the war is already there, it’s a nonviolent information war, cyberwar, political warfare – China has already developed a new institutional system that adapted to the war. The damage has already begun.

After 2020, when the national security law was imposed in Hong Kong, about 300,000 people left in three years. We don’t have the number of how many people left the mainland but the existence of the “Run movement” indicates it was a lot. I went to Tokyo, and to Chiang Mai, and to other cities and met so many old friends in places where I never thought I’d see them. They’re still young, still mid-career, so they’re trying to find their new chances in different countries. My focus became figuring out how to mobilize these people — how to build community in a decentralized manner. Can we still build an alternative Chinese society in a free, peaceful, autonomous way?

Right now, I’m just getting started. I founded a small bookstore about fifteen months ago, it’s called Now Here, but you can call it No Where. You can always start from where you are.