America Is Not America Yet

On American history and the history of the word “America.”

OCTOBER 3, 2024

As a word and concept used to describe the lands of the Western Hemisphere centuries ago, America did not have to be “America.”

In the years and decades after Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the island of Guanahaní in 1492, European cartographers trialed various other possibilities: “Parias,” “Tierra Incognita,” “Prisilia,” “Terra Nova” and “Terra Parias,” to name a few. The Spanish Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas suggested “Columba.” In 1561, a French geographer offered “Atlantis.”

But none stuck like the original designation, invented in 1507 by a small group of German humanist scholars in what is now northeastern France to honor Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine explorer who claimed to have “discovered” America.

The naming of America and its peoples, as the Haitian philosopher Jean Casimir reminds us, constituted “expediencies of European discourse.” As such, this history of naming is a history of power. The power to name the unknown was to render America knowable and legible within European frames of understanding. But for what purposes? For whose interests and ambitions?

Today the question of who gets to be American remains unsolved and highly charged. Amid this debate — which touches on identity and immigration, history and economics — it is worth asking: What do we mean when we say “America”?

I. The Europeans

In a letter to his patron published in 1503 as Mundus novus, the Florentine navigator Amerigo Vespucci claimed to have discovered “a new world.” He had traveled to the unknown lands beginning in the late 1400s; the circulation of his writings throughout Europe in the early 1500s publicly made him the first discoverer. Though academics have since cast doubt on the veracity and authorship of Vespucci’s works, in 1507 the scholars working in St-Dié, Duchy of Lorraine, to produce a new cosmography and world map chose his name to label the region we now know as South America.

By the 1600s, the consistent use of “America” by the Flemish and Dutch cartographers who dominated transatlantic trade ensured its survival.

“I do not see why anyone could justly object to naming it Amerigen, after Americus its discoverer (a man of keen talents), the land of Americus as it were, or America, since Europe and Asia received their names from women,” one of the scholars wrote in the famous Cosmographiae introductio.

Use of the name spread unevenly throughout Western Europe for the rest of the century. In some cases, scholars who initially used the name later dropped it as they engaged with new travel narratives and information. Martin Waldseemüller, a co-author of Cosmographiae introductio, replaced “America” with “Terra Nova” in his last map, from 1516. But by the 1600s, the historian Christine Johnson tells us, the consistent use of “America” by the Flemish and Dutch cartographers who dominated transatlantic trade ensured its survival.

This naming process occurred during a world-defining historical moment. Between 1490 and 1530, Western Europe — until then a relative backwater compared with the Ottoman Empire or Ming China — emerged on the threshold of global dominance. These four decades, the historian Patrick Wyman argues in his recent book The Verge, set the scene for the rise of the so-called West and the “great divergence” between Western Europe and its Asian competitors.

This rise was buttressed by novelties such as the creation of modern nation-states through war, the development of new financial instruments and the circulation of ideas (especially religious propaganda) via the printing press. These advances fundamentally depended on the global imperial expansion and colonial conquests that began after 1492. The long story of “America” as a word and concept thus began during this nascent moment of bloody European ascendancy.

And yet the people of America had their own names, their own cosmographies. The Kuna spoke of Abya Yala. Several Indigenous peoples who live in what is now North America share origin stories that describe their region as Turtle Island. Powerful Indigenous polities in Mexico and Andean South America called their worlds Anáhuac and Tawantinsuyu. In 1600s colonial Brazil, a quilombo — a liberated community founded by runaway slaves — named Palmares lasted nearly 100 years, fending off numerous colonial offensives.

In 1804, victorious Black revolutionaries who formed part of the “Indigenous Army” that defeated three European empires in 13 years decided to rename their liberated abolitionist island. They replaced French colonial Saint-Domingue with Aytí/Haiti, an Indigenous Taíno name for the island. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the leader of the Haitian revolutionaries, framed the victory as an exercise of historical redemption and justice. “I have avenged America,” he wrote.

These “avengers of the New World” offered a vision of what America could be: anti-slavery, anti-colonial and anti-capitalist. And it shook the world.

II. The Revolutionaries

America: What began as a European expediency fueled an array of anti-colonial, anti-imperialist imaginations and movements.

In Baracoa, Cuba, a statue commemorates the first rebel of America. Hatuey, a Taíno leader, helped lead the armed resistance against the Spanish in the early 1500s on the island of Hispaniola. Some of the enslaved Africans forced to the island by the Spaniards escaped, joined the rebellious Taíno and — according to the colonial governor — “taught them bad customs.” Around 1511, Hatuey fled with hundreds of followers to nearby Cuba to warn local populations about Spanish brutality and organize a campaign of armed struggle.

During this Age of Revolutions, as historians would later call it, “America” and “American” came to be used as anti-colonial identities.

Spanish conquistadors captured Hatuey in 1512 and sentenced him to death by being burned at the stake. When a Franciscan friar pleaded with the rebel leader to accept baptism and die as a Christian, Hatuey responded, “I don’t want to go where Spaniards go.” He preferred hell.

America generated many more rebels during an era of unfettered European colonialism that lasted, in most parts of the region, well into the early 1800s. In that period, white settlers born in America imagined and actualized a distinct political identity separate from their colonizer ancestors and European imperial rulers. Some in the earlier settler generations had imagined America in religiously utopian and millenarian terms: Free from Europe, the new Babylon — America — offered the possibility of making a new Zion, a new Jerusalem. The end times and the second coming of Christ were at hand for Franciscan friars in 1500s Mexico and Puritan preachers like Cotton Mather and Samuel Sewell in late 1600s New England — if only they could convert enough of the Indigenous peoples suffering European genocide, enslavement and disease.

Unsurprisingly, these forms of domination generated resistance from Indigenous peoples, sometimes in the form of mass insurrections. From King Philip’s War of 1675-1678 and the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 to Túpac Amaru II’s 1780 multiracial rebellion in the Andes, to kill a European was to fight for anti-colonial liberation.

During this Age of Revolutions, as historians would later call it, “America” and “American” came to be used as anti-colonial identities. But these identities were shot through with the same kinds of racial hierarchies and ideas of domination and separation that structured colonial societies.

In Spain’s racial caste colonial societies, mestizo (mixed-race) descendants of Indigenous nobility and Creoles — Spaniards born in the Americas — writing in the 1600s helped set the foundations for the emergence of an American identity separate from Europe. Noble mestizos in New Spain and Peru produced histories of the Mexica (Aztecs) and Incas that challenged self-serving Spanish depictions of these Indigenous polities as “barbarian” and “tyrannical.” These histories served as early critiques of Spanish colonial rule while generally stopping short of calling for the overthrow of colonial hierarchies.

Creole intellectuals, too, looked to preconquest Indigenous pasts to help forge an American “creole patriotism” by the 1700s. Yet even as they valorized the achievements of past Indigenous empires, Creoles tended to minimize the conditions of existing Indigenous communities — not to mention the mixed-race, enslaved and free Black communities.

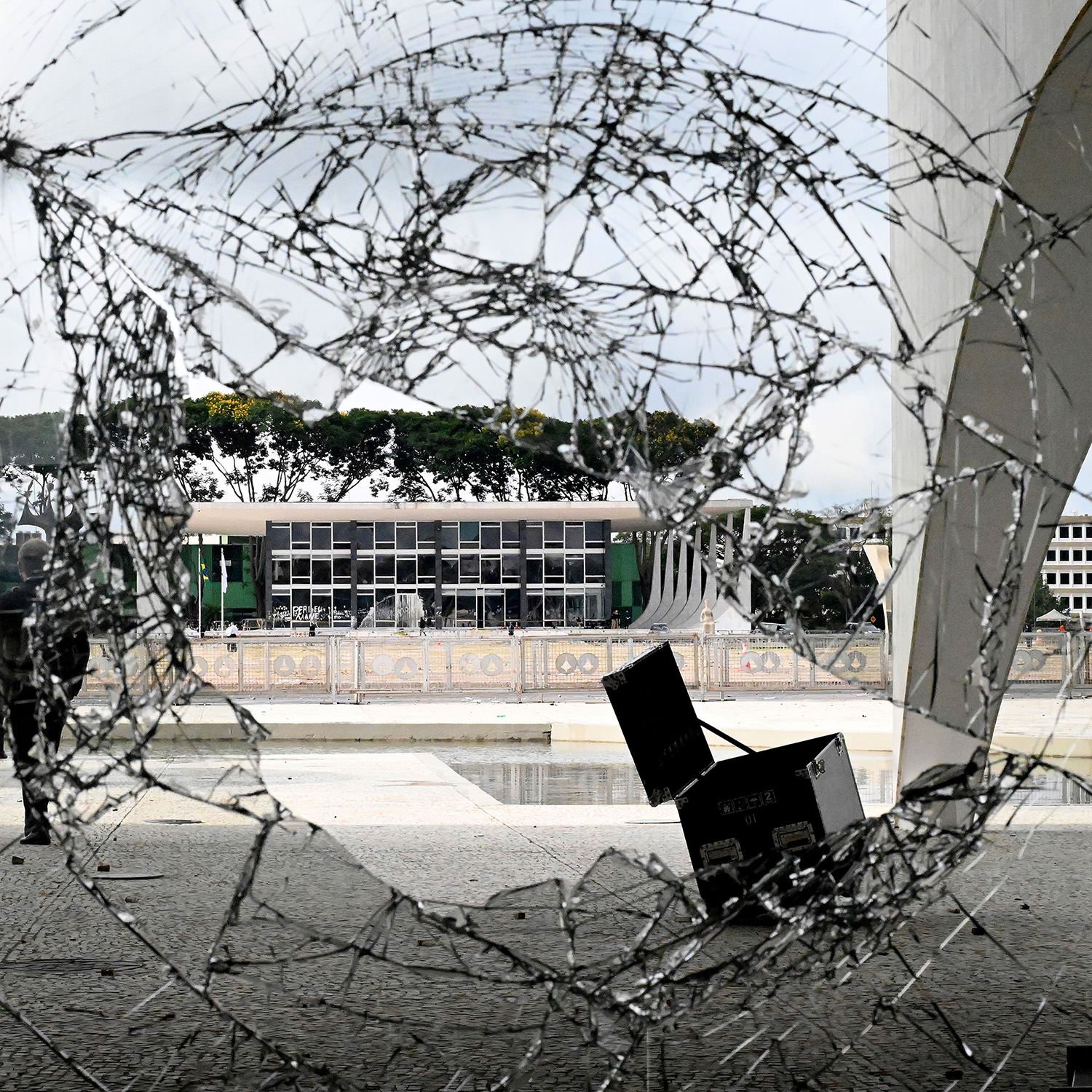

This contradiction — a testament to Spanish colonial societies predicated on Catholic orthodoxy, “blood purity” and racial separation — would continue to plague most new nations that emerged from the Spanish American Wars of Independence of 1808 to 1826. If wars of national liberation had turned “America”/“American” into broadly inclusive categories, the ensuing decades displayed an exclusionary narrowing. Creoles simply replaced the Spanish at the top of racially stratified, exploitative regimes, and republics replaced the crown; domination continued under new names. “Same horse, different rider,” the old Latin American saying went.

Yet in New Spain, creole patriotism proved capacious enough to become an anti-colonial and revolutionary political ideology capable of attracting mass support during its independence wars of the early 1800s. One religious symbol in particular — created by local Indigenous communities early in the colonial period and later appropriated by Creoles — proved capable of unifying communities across racial caste lines: The American Virgin of Guadalupe contested the Spanish Virgin of Los Remedios and served as the battle standard for several anti-colonial armies led by rogue priests like Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos.

When Morelos wrote “Sentiments of a Nation” in 1813, a broad outline for a republican independent nation, he included a point that set aside December 12 as a day to celebrate the rebel American Virgin. That same document called for the end of colonial monarchical tyranny, abolition of slavery, elimination of the racial caste system and the expulsion of “the enemy Spaniards.” America for Americans.

Upon independence in 1821, this colony-turned-nation shed its European designation and renamed itself Mexico — after one of those past Indigenous empires valorized by Creoles. The creole tendency to marginalize living Indigenous communities, too, survived independence.

III. The Latin Americans

If the Age of Revolutions resulted in a separation between Europe and most of America, the second half of the 19th century witnessed a split in the hemisphere — between Anglo America in the north and Latin America in the south.

The story of this split essentially tracks with the expansion of the United States empire. As Europe’s most successful settler colony expanded its brutal campaign against Native Americans in the first half of the 1800s, some of its most prominent figures looked south to its newly independent neighbors. And they gradually imagined a profound civilizational divide — at times expressed in racial terms — between a liberal republican U.S. propelled into the future by Manifest Destiny and a disparate assortment of former Spanish colonies incapable of escaping backward feudal legacies.

Writing in 1815, a decade before he became president, John Quincy Adams articulated an evaluation that has not entirely disappeared from the U.S. mindset: “The people of South America are the most ignorant, the most bigoted, the most superstitious of all the Roman Catholics in Christendom,” he wrote in a letter to James Lloyd, a senator from Massachusetts. Any plan to establish free, democratic governments “appeared to me as absurd as Similar plans would be to establish Democracies among the Beasts, Birds or Fishes.”

It would take mobilization from below — the revolutionary movements that shook the region throughout the 20th century — to make the idea more inclusive, more radical, more anti-imperialist.

This sort of thinking helped justify U.S. imperial domination of the hemisphere throughout the 19th century. So, too, did the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, originally intended as a warning for European powers with colonial designs to stay out of the Americas. The doctrine and its ensuing corollaries legitimized U.S. efforts to make America, the name and the region, theirs and only theirs. In 1858, 12 years after the U.S. invaded Mexico and plundered between one-third and one-half of Mexican national territory, The New York Times published an article advocating the “necessity” of establishing a “Mexican protectorate.” It was a matter of national interest and imperial duty: “We are not merely the leading, but the controlling power on this Continent,” the paper’s correspondent wrote.

But it wasn’t the Mexican-American War that sparked the development of a Latin American identity in opposition to the U.S. A few radical intellectuals, the Chilean Francisco Bilbao in particular, had started discussing the idea of a united “Latin” America to counteract U.S. empire during the late 1840s and early 1850s. Not long after, William Walker’s invasion of Nicaragua in 1856 sparked “the largest anti-U.S. alliance in Latin American history.” The idea of a Latin America spread throughout the region, fueled by an anti-imperialism that ensured its durability and consistency.

Yet, as the historian Michel Gobat notes, this early Latin Americanism proved to be largely white and driven by elites. The assimilation of nonwhite populations — which made up most of the region — remained a possibility, but only within terms set by the descendants of Creoles. As such, “a tension between inclusion and exclusion marked the idea of Latin America from the very start.” It would take mobilization from below — the revolutionary movements that shook the region throughout the 20th century — to make the idea more inclusive, more radical, more anti-imperialist.

In his famous article “Our America,” published in 1891, the Cuban revolutionary leader José Martí argued in favor of egalitarianism for the sake of regional unity and justice: “The scorn of our formidable neighbor who does not know us is our America’s greatest danger.”

The America of equality and liberty, the “homeland of the free,” as the poet Langston Hughes wrote, “never was America to me.”

Latin America knew and felt that scorn. The U.S. was rather clear about it. When U.S. delegates at the 1889 Pan-American Conference tried to “strengthen the Monroe Doctrine’s ‘America for the [Anglo] Americans’ clause,” the Argentine delegation presented an alternative. They called it “America for humanity.” The U.S. would go on to invade Latin America at least 34 times by the early 1930s.

IV. America

If the current political discourse — particularly around migration and refugees —is any indication, these civilizational divides remain alive and well. And the truth is that Indigenous America, Black America and Latin America are all here in the United States. They always have been — their land, their labor, their cultures, their dreams, their hopes.

This country began as an exclusionary and hierarchical project, caught between lofty philosophical ideals of freedom and the white supremacist slaveholders who uttered them. Thomas Jefferson could speak and write of freedom without blushing; George Washington’s dentures included the teeth of his Black slaves. The America of equality and liberty, the “homeland of the free,” as the poet Langston Hughes wrote, “never was America to me.” Yet Hughes, and millions more, believed in the promise of a radically egalitarian America, an America “that never has been yet — and yet must be” for the working masses who made and make this country. Hughes offered a vision born of the tension between the racial apartheid he knew and the hopeful possibility of revolutionary redemption.

In other words, “America” as we know it today doesn’t have to be this way. It could be something else.

In this U.S. election year, I do not see the possibility of Hughes’ yet-to-be-America in the halls of political power. I do not see it in the vicious racial and misogynistic revanchism of the Republican Party. Nor do I see it in the superficial “politics of joy” of the Democratic Party, which excels at hearing us and seeing us without carrying out much meaningful action. Instead, it uses the specter of a Trump victory to shut down critical interrogation of its policies in West Asia, its failure to protect reproductive rights and its de facto shutdown of asylum rights for refugees at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Instead, I see possibility in the streets and on university campuses, with protesters decrying their government’s support for the mass bombing of civilian populations in Gaza and Lebanon; on Indigenous lands, with the water protectors and land defenders; in labor organizers working to increase the power of unions; in Black and brown abolitionist community groups still organizing against police brutality; in the migrant caravans traveling the length of the American continent, fleeing countries devastated by U.S. policies.

At the very least, these movements collectively offer a more just, humane and internationalist vision of what America could be. America is much more than the United States. Through protest and struggle, these movements interrogate the root causes of our monstrous status quo — a necessary first step on the path to imagining and creating something else. Struggle is a wager, not a guarantee. But without struggle, as Frederick Douglass reminds us, there is no progress.

America, you see, does not exist. I know. I’ve been there. But it might yet.