States of Sanctuary

As governments across the world crack down on migration, can alternatives to asylum make a difference?

JULY 3, 2024

In September 2023, something unusual happened on the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa: The detention center for asylum-seekers threw open its doors. Lampedusa, which is part of the Sicily region, is the first point of arrival in the European Union for many African refugees and immigrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea from Libya and Tunisia. For years the Italian government has operated a “hotspot” on Lampedusa: its term for a closed center that shelters new arrivals and processes their identification, registration and fingerprints. The hotspot had room for 400 people, but between Sept. 11 and Sept. 17, more than 11,000 arrived on small boats to the island. The ordinary border procedures collapsed.

For a week, the new arrivals to the island had total freedom of movement. Lampedusa residents cooked and distributed platters of fish ravioli, arancini, pasta and couscous. “Lampedusa streets, public spaces, benches and bars, have been filled with encounters, conversations, pizzas and coffees offered by local inhabitants,” the activist network Maldusa recounted on its website. “Without hotspots and segregation mechanisms, Lampedusa becomes a space for enriching encounters and spontaneous acts of solidarity between locals and newly arrived people.” It was a glimpse into a different reality, one of inclusion rather than exclusion. But as arrivals to the island slowed, the hotspot resumed operations.

Across the continent, governments criminalize migration, scale up deportations, scale down assistance, surveil asylum-seekers and interrogate humanitarian groups.

I had started reporting on migration in the summer of 2015, when more than 1 million Syrian, Iraqi, Afghan, Sudanese, Eritrean and other refugees fleeing conflicts, persecution and poverty arrived to the EU. Since then, people trying to move into Europe from other continents have been increasingly persecuted. At the EU’s external borders, guards beat people back, and coast guards ignore calls from ships in distress. Across the continent, governments criminalize migration, scale up deportations, scale down assistance, surveil asylum-seekers and interrogate humanitarian groups. Several countries are in the process of establishing “reception” facilities outside their territory, where asylum-seekers can be indefinitely detained. (In April, for example, the UK passed a law that will enable the transfer of asylum-seekers to Rwanda, while Italy plans to send them to Albania).

As Europe’s governments strengthen the barricades, citizen movements like Maldusa are experimenting, across the continent, with how best to challenge them. In Berlin, where I live, I found an array of grassroots coalitions that are defying anti-migration policies, including an organization of artists that helps other artists escape danger outside the confines of the asylum system. Learning more about these movements sent me to Palermo, the capital of Sicily, which is on the front lines of migration debates. There, I met advocates for freedom of movement — the right of anyone to travel and set up home anywhere — who are building cross-border alliances. These groups are up against powerful governments, and they are aware that there is a limit to what they can achieve. Yet in both Berlin and Palermo, activists are committed — no matter the odds — to a vision radically different from that of Europe’s politicians: a world that is expansive, collaborative and free.

✺

In March 2016, an exhibition called “Women and Diyarbakır Prison Nr 5” opened in Diyarbakır, Turkey, curated by the Kurdish artist Bariş Seyitvan, then 33 years old. In the early 1980s, the Turkish military government jailed and tortured hundreds of Kurdish politicians and citizens in a prison in Diyarbakır, in the southeast of the country. Seyitvan’s installation featured photos, videos and letters from female prisoners and the wives, sisters and mothers of imprisoned men, 34 of whom died inside.

Political leaders in Turkey have long viewed the Kurdish population as a threat. Diyarbakır is Turkey’s largest Kurdish-majority city, with a population of some 1.9 million in the municipality. Since the mid-1980s, it has been caught in violent clashes between Kurdish separatist groups and government forces. Seyitvan understood that there might be backlash to his exhibition and didn’t include his name on any promotional materials. A few days after the exhibition opened, he got a call from a friend who worked at the local police station. “Don’t come to the gallery,” the friend said. “The police are here, and they want to know who arranged the exhibition.”

The exhibition coincided with yet another government crackdown on Kurdish politics, art, culture and language. First the police closed the gallery. Then they shuttered Diyarbakır’s culture centers, a conservatory, two Kurdish-language kindergartens, a Kurdish TV channel and children’s TV programming. Finally they deposed the city’s two democratically elected Kurdish mayors, and Recep Erdoğan, the country’s president, installed his own.

Seyitvan figured it was best to leave town. He went to Izmir, a city perched on the Aegean Sea some 880 miles west, where there was less of a police presence. Seyitvan’s wife, a teacher, remained in Diyarbakır, and Seyitvan traveled back and forth between the two cities. The following year, he went to Berlin for a panel on Kurdish art, where he met a Finnish curator named Marita Muukkonen. A few years prior, Muukkonen and her American French partner Ivor Stodolsky had founded Artists at Risk, a Berlin-based organization that helps artists escape persecution by providing them with temporary safe havens. Muukkonen told Seyitvan to stay in touch.

As time passed and Seyitvan heard nothing from the Turkish government, he began to assume he was no longer a person of interest. On a trip back to Diyarbakır in the summer of 2018, he pulled into the parking lot of the local Ikea with two friends to run some errands. They were stopped by the police for an ID check, and Seyitvan was arrested. At the police station, he was taken to the “terrorist organization department,” where officials pulled out photos of “Women and Diyarbakır Prison Nr 5.” They told Seyitvan that the exhibition was terrorist propaganda and that they suspected him of organizing it. The police had a thick file on Seyitvan that included his social media posts, a talk he gave in Kraków, his artwork. They released him after two days of interrogation. He was given a court date for when he would face terrorism-related charges.

Human rights organizations have documented the Turkish government’s use of charges to silence Kurdish and other artists, politicians and dissidents. Seyitvan texted Muukkonen and Stodolsky and got an immediate response.

Can you please explain your current situation?

You have to leave by February 2019?

Yes.

Do you have a lawyer?

Yes.

Ok we need a timeline of what happened – please fill in this form.

Seyitvan completed an online application to Artists at Risk with the details of his case. Artists at Risk moves rapidly, unlike the resettlement programs of the United Nations Refugee Agency or individual governments, which can take months or years to kick into gear. A few weeks after he sent his application, Seyitvan was matched with a three-month residency sponsored by the Helsinki International Artist Program. On Jan. 31, 2019, Seyitvan flew to Finland, leaving behind his wife and two boys. Artists at Risk told him that it would help bring his family over later but that it was better for him to get out while he still could. He has not been home since.

✺

Stodolsky and Muukkonen hadn’t intended to run emergency relocations. When the Arab Spring took off at the end of 2010, they watched in alarm as artists became the targets of brutal crackdowns across North Africa and the Middle East. “Many of our peers were in a situation where they had to get out temporarily,” Stodolsky told me last fall, when we met for breakfast in a café in Berlin’s Neukölln neighborhood. “They needed a breather.” Stodolsky and Muukkonen had been living in Helsinki at the time. They found a way to quickly relocate several artists by partnering with local residencies to provide housing, studios and visa invitation letters. In 2013, they founded Artists at Risk. While existing initiatives like the International Cities of Refuge Network and PEN International relocated persecuted writers, no organization at the time was aiding photographers, curators, painters and filmmakers. Stodolsky and Muukkonen scoured Europe for host institutions. These institutions were typically independent art or cultural centers that could provide refuge for artists for anywhere from a few months up to a year, though city governments — such as Barcelona — also signed up to provide support. It was critical to Stodolsky and Muukkonen that the artists could work in exile, so they curated interdisciplinary shows around the world featuring the work of those in the program.

Artists at Risk does not recommend that its artists apply for asylum, which typically bars the applicant from working and forces them to relinquish their original nationality. Instead, the organization views artists as defenders of human rights who need the ability to move back to their home country, temporarily or permanently, if desired. One of first artists it helped was the Syrian photographer and director Issa Touma, who applied in 2013 from an Aleppo under siege. He needed electricity to finish editing a film, and the power supply in Syria was unreliable because of the war. After a three-month stint at a Helsinki residency working on his film, Touma returned to Aleppo. Other artists, like Seyitvan, require the ability to stay in a new country long-term. Depending on its risk analysis, the organization might relocate someone within a country (such as to a safe house to escape immediate physical danger), within the region (such as to a neighboring country, where paperwork may not be required to enter) or to a country where a visa is required, as was the case with Seyitvan.

Each morning when Seyitvan woke up, often in the dark before the sun rose, his first thought was, I’m here, on an island, in Finland. And then – I can’t go back.

From February 2022 to the end of 2023, Artists at Risk received 6,236 applications — vastly more than their budget and staff of around 15 people, working virtually, could accommodate. During this period, the group relocated 767 people to 302 host organizations, the majority inside the EU. Of these artists, 602 were Ukrainian, 92 were Russian or Belarusian, 51 were Afghan, and 22 came from other hostile regimes or violent conflicts. The organization was only able to help so many artists from Ukraine, Stodolsky and Muukkonen told me, because of the EU’s decision to issue a blanket “temporary protection” category for Ukrainians, which entitled them to residence permits, health insurance and other benefits. The protection did not extend to foreign nationals who lived in Ukraine and also needed to flee the war.

European art institutions and funders were also quick to support Ukrainian artists. Stodolsky and Muukkonen tried to build off this enthusiasm by asking institutions to host artists from anywhere in the world or ensure the funding was unrestricted, but not everyone was willing. “It’s often like that in the field of art; there are these kind of trendy things … then the next thing happens, and [everyone] moves on,” Muukkonen said.

By late 2019, Seyitvan had been hopping between different artist residencies for a year. He spent his first three months of exile on the grounds of a former prison turned cultural center on Suomenlinna, a short ferry from Helsinki. Each morning when Seyitvan woke up, often in the dark before the sun rose, his first thought was, I’m here, on an island, in Finland. And then – I can’t go back.

Each day he video called his two children. “When are you coming home?” they asked. Seyitvan experimented with performance art; one day he sent a dozen people to walk through Helsinki’s downtown wearing the same neon orange life vests commonly worn by people crossing the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe.

After Finland, Artists at Risk matched Seyitvan with a German institution that offered him a yearlong placement. But when Seyitvan went to complete the application, he learned that he had to be a German resident to accept. Due to EU visa rules, he could not apply for a visa from inside the bloc, and so he first completed another six-week residency in the Balkans while he waited for the Germans to approve him. He moved to Berlin in February 2020.

When coronavirus struck, Seyitvan’s wife and children had not yet arrived in Germany, so he weathered the pandemic alone. He didn’t have a studio, and in the early days, before he found stable housing, he sometimes worked below ground in the U-Bahn, Berlin’s metro, where there was free Wi-Fi.

Artists at Risk advocates for artists, whom it believes have a special status as defenders of human rights. As I attended rallies and meetings with other pro-migration groups in Berlin, I considered the many people who don’t fall under this category but still need to leave their countries, alone or with their families. How do communities organize to facilitate their movement? A month after meeting Muukkonen and Stodolsky, I flew to Palermo, on Sicily’s northwestern edge, to see what sanctuary activism looks like in a city near the busy migration route of the Mediterranean Sea.

Sicily — which is both a large volcanic island and a region encompassing other small islands in the Mediterranean — has a long history of people coming and going. Before becoming part of the modern Italian state, it was ruled by the Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Swabians, French, Spanish and Bourbons. Today, because of its location some 95 miles from the Tunisian coast, it is often the first stop for people crossing from North Africa to Europe.

Most of these people are unable to obtain a visa in advance, and their journeys are dangerous. This wasn’t always the case. In the 1980s and early ’90s, traveling between the North African coast and Sicily was relatively easy: There were daily ferries, and people with Tunisian passports could visit Italy without a visa. In 1997, however, Italy entered the EU’s Schengen Agreement, which imposed a common visa policy for those outside EU territory and made it more difficult for non-EU citizens to enter the bloc.

EU law stipulates that people have to stay in the first country where they seek asylum. A decade ago, most people who arrived in southern Italy from North Africa were able to ignore this law and quickly head to northern European countries with stronger economies. But in the past decade, as the EU set up biometric fingerprinting upon arrival, installed fencing and surveillance along its external borders, and invested in its own border guards, it became easier to trace people’s routes. Those who tried to move on from Italy or Greece to countries like Germany and France could be deported back to wherever they had entered the EU to wait out a decision on their case. As a result, increasing numbers of people have stayed in Sicily and begun organizing.

“We believe that freedom of movement is not only moving but also arriving and being welcomed in different ways.”

The Maldusa network is one product of this mobilization. Created in 2022 by longtime border and migration activists, it brings together disparate social justice groups with a broader goal of freedom of movement on land and at sea. Whereas an earlier generation of migration activists might have seen themselves as offering sanctuary, Maldusa organizers are more likely to talk about solidarity: They regard themselves as cocreating a refuge with those who need it rather than providing one. The network runs two physical centers, both located in Sicily — one in Palermo and one in Lampedusa. Maldusa calls these centers “stations” — a reference to the American Underground Railroad, which helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Recently, the network purchased a motorboat to monitor the waters between Italy and Malta, where migrant boats often float in a kind of rescue black hole, each coast guard claiming they’re the rescue responsibility of the other. Maldusa can now pressure authorities to intervene when ships are in distress.

I arrived in Palermo in late November, when the city was covered by a pale gray sky. Oranges hung low on the trees. The Maldusa station, which opened in April 2023, is tucked into the city’s core, close to the sea that borders the city’s eastern edge. The space provides information for new arrivals to the city and hosts trainings, film screenings, festivals, book clubs and a weekly aperitivo. At the station’s ramshackle entrance, I found Said Kdiss lounging outside on a rare break from work, smoking a cigarette and drinking a coffee while stretching his long legs. Kdiss, who’s Tunisian, arrived in Sicily in 2011 when he was 17. His age gave him the right to remain in Italy until he turned 21, when he found a job and subsequently obtained a work permit, turning his illegal entry legal. He is now a floating cultural mediator, hired by the government and by nongovernmental organizations to facilitate their work with asylum-seekers. “Here it’s like North Africa,” Kdiss told me as the sun broke through the haze. “I’m still home.”

Inside the Maldusa station there is Wi-Fi and a small library; outside there is a patio with pallet couches, a conch shell for an ashtray and a rotating array of dogs. During the week I was there, the office buzzed with people conducting research and organizing meetings for different initiatives, such as Borderline Europe, a German organization that helps coordinate Alarm Phone, the 24/7 emergency hotline for ships in distress crossing the Mediterranean Sea. “We believe that freedom of movement is not only moving but also arriving and being welcomed in different ways,” said Camille, a French researcher on prison abolition and a Maldusa member. (Camille asked that her last name be withheld due to concerns about increasing surveillance of activists).

Many of the activists I spoke to in Palermo preferred not to think in the legal terms used by governments, the U.N. and, often, the media: “asylum-seekers,” “refugees,” “migrants.” Their goal was to help anyone who needed it, wherever they came from and whatever their official immigration status.

One afternoon at Maldusa I met Madieye, who is originally from West Africa. (He asked that I not use his last name or nationality.) Madieye is a well-known figure at Maldusa, part of the organization’s Baye Fall association, which helps new immigrants from West Africa find their bearings in Palermo. In July 2013, Madieye took a boat from the Libyan coast to Italy. The passengers were told that they had to navigate themselves. Once at sea, they started to drift, and Madieye took the wheel to prevent capsizing. When the ship arrived in Sicily, the Italian police immediately arrested Madieye and charged him with smuggling.

Prosecutions take years to wind through the Italian court system. After a decade, Madieye was cleared of all charges, but news of arrests like his had reached the other side of the sea, and people had become afraid to take the wheel once a boat crossed into international waters. A boat without a captain, Madieye told me, is more likely to overturn, leading to more drownings. At Maldusa, I picked up flyers in French for Captain Support, a platform that links lawyers with people accused of driving boats to Europe. In 2023, Italy arrested some 200 boat drivers for smuggling, part of a broader strategy to prevent further movement by criminalizing it. The Italian government has also charged humanitarian groups that perform rescues at sea with aiding illegal immigration.

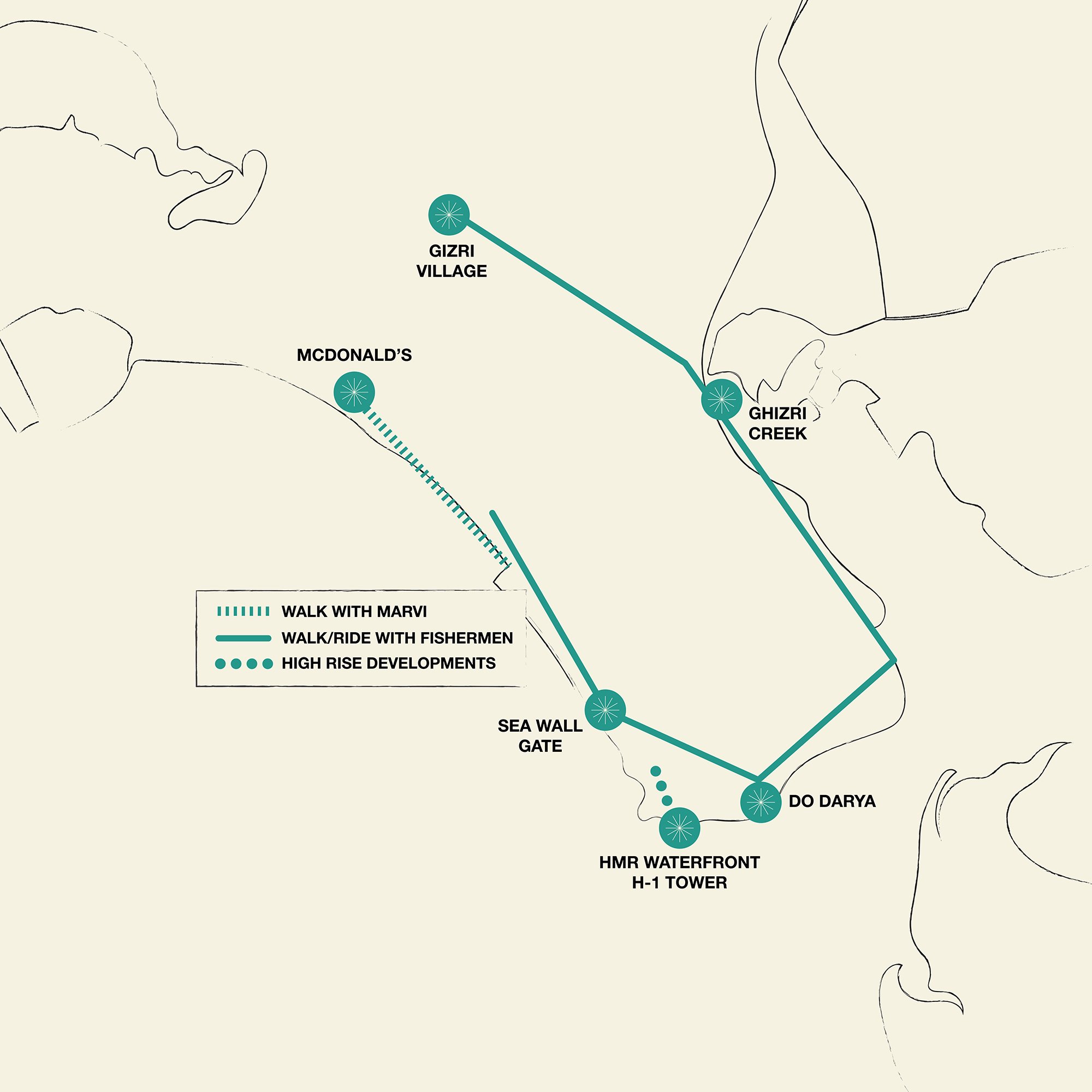

Over the years, activists in Palermo have witnessed how migration routes evolve. Richard Braude, who helps run the Porco Rosso Sans-Papiers drop-in legal clinic in the city, told me that the clinic’s once mostly young West African male population has shifted to include women and the elderly. Recently there have also been Palestinians, Kurds, Bangladeshis, and Peruvians who emigrated through Spain. “People move where the border systems allow,” Braude said. Many of the activists I spoke to in Palermo preferred not to think in the legal terms used by governments, the U.N. and, often, the media: “asylum-seekers,” “refugees,” “migrants.” Their goal was to help anyone who needed it, wherever they came from and whatever their official immigration status.

The migration scholar Dawn Chatty has critiqued the Western approach to asylum, where only those who legally qualify as refugees are granted protection. This approach, Chatty argues, has perverted a normal human impulse — to help those in need — by sorting asylum-seekers into categories and withholding refuge from those who do not fit into narrow legal parameters. Instead, Chatty calls for a “holistic approach which taps into the social and ethical norms of hospitality in local contexts,” as has sometimes been the case in the Middle East, where several countries have allowed for the mass movement of people without relying on an asylum system. It seemed to me that that’s what organizations like Maldusa were trying to do.

Palermo has huge heaps of trash lying on the sidewalk, a housing crisis and a “shit economy,” as Braude put it. But the city also felt energetic and welcoming. On a morning when Sahara dust coated the streets, Kdiss took me to Centro Astalli, a soup kitchen inside a church that offers everyone — immigrant or Sicilian — a hot breakfast. In a café called Moltivolti, I saw a map on the wall, routes across countries marked on it with fuzzy red thread. Above the map, a sign: La mia terra è dove poggio i miei piedi. Home is where I rest my feet.

✺

When Seyitvan left Turkey, he had no idea where he would end up. In many ways, Berlin seemed alluring: The city has a significant Kurdish population and numerous galleries and museums. In February 2024, when Seyitvan and I hopped between a series of Kurdish cafés in Kreuzberg, he knew many of the waiters by name. Yet Berlin is also increasingly expensive, and many of its artists are migrating elsewhere.

Seyitvan, who is short and lithe with a scruffy goatee, told me that the other day his father, who is now 75, called him from Diyarbakir and said he had dreamed about his mother, Seyitvan’s grandmother, who had died before Seyitvan was born. “I woke up crying,” the older man said. “She told me, ‘I am going to Bariş’ home.’” Seyitvan said he did not know whether that meant the home where he grew up or the one he is trying to make in Berlin.

Bariş Seyitvan in Berlin (Photo by Carleen Coulter)

Seyitvan’s wife and children arrived in Berlin in early 2023, and he is now a legal resident of Germany. But he still doesn’t feel that his family is entirely safe. There have been murders of Kurds in Europe — such as in December 2022, when three people were killed at a Kurdish cultural center in Paris — and fascist and racist attacks on immigrants in Germany. Germany is a steadfast ally of the Turkish government. Every time Seyitvan speaks on a panel or organizes an event in Berlin, he suspects there is someone in the audience adding pages to his file. Still, Seyitvan creates: In April, he installed a live olive tree in the Artists at Risk pavilion in the Venice Biennale, a reminder of the 2018 Turkish military’s “Operation Olive Branch,” when soldiers entered the Kurdish town of Afrin, killing hundreds of people.

At the end of 2023, the EU finalized the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, a policy that expands detention, including for children; creates swifter procedures with limited time for appeals; and continues funding authoritarian regimes elsewhere to prevent people from crossing by land and sea routes. The European Parliament elections held in early June resulted in significant gains for far-right parties with anti-migration agendas, suggesting that even more punitive proposals could emerge. Just before the elections, 15 EU countries sent a letter to the European Commission — the EU’s executive arm — calling for asylum-seekers to be forcibly sent to a “safe third country” for “processing,” instead of allowed inside the EU.

In response, Artists at Risk has been campaigning for the creation of a new visa category for defenders of human rights, to make it easier for artists to move when in danger. It’s also seeking safe routes outside of the EU, such as between East Africa and southern Africa, and working to secure visas for Palestinian artists in Gaza. In Sicily, Maldusa’s motorboat is now operational, surveying the waters.

Braude, the organizer I spoke with at the legal clinic in Palermo, described the world’s border regime to me as a series of openings. It made me think of a sculpture on Lampedusa: a 16-foot-high ceramic wall facing the sea, with an open doorway through which one can enter or exit. The Italian artist Mimmo Paladino built the “Gate to Europe” in 2008 as a monument to the men, women and children who had died before they could reach land — some 27,000 in the past decade, and counting. The question for activists was whether to open more doors — or eventually, to tear the whole house down.

This story was supported with a grant from the Robert B. Silvers Foundation.