England’s New Surveillance Regime Over Reproductive Rights

In Britain, phone data is being used to prosecute women who seek abortions.

JANUARY 30, 2024

On June 12, 2023, British High Court Judge Sir Edward Pepperal, presiding judge of England’s Midland Circuit, sentenced mother of three Carla Foster, 44, to 28 months in prison. Her crime: accessing an abortion after 24 weeks of pregnancy, the legal upper-time limit in England and Wales. Foster spent one month in prison before being released on appeal.

The evidence against Foster included a tranche of her own digital data: her online search history, texts, and phone records had been presented to the court. In his sentencing remarks, Judge Pepperal cited specific messages found in Foster’s data, saying: “messages found on your phone indicate that you had known of your pregnancy for about three months on 1 February 2020,” he wrote. “By mid-February, you were conducting internet searches on ways to induce a miscarriage. By the end of February, you were searching for abortion services. Your search on 25 February indicated that you then believed that you were 23 weeks pregnant. Your internet searches continued sporadically through March and April 2020.” In one online search, conducted on April 24, 2020, Foster typed, “I need to have an abortion but I’m past 24 weeks.”

In July, the Court of Appeal gave Foster a 14-month suspended sentence. “It is a case in our view that calls for compassion, not punishment, and it is one where no useful purpose is achieved by detaining Ms Foster in custody,” the judge, Dame Victoria Sharp, ruled. By the time of her release, Foster’s case had already caused uproar and outrage across Britain. Not only did it bring renewed attention to the country’s regressive abortion laws, but it also alerted the public to how expanding online surveillance makes it easier to prosecute women who have accessed abortions outside the legal limits. In Britain, women can face life imprisonment under the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861, which criminalises procuring or administering drugs or instruments to cause abortion.

“This is worse than countries and states with severe anti-abortion laws such as Texas, Afghanistan, and South Sudan. We are on the wrong side of history.”

“No woman should ever be criminalised for abortion related offences which date back to the Victorian era when women did not even have a right to vote,” said Barrister Dr. Charlotte Proudman. “Unfortunately, Foster’s case isn’t an outlier — there’s a concerning rise in criminal investigations into women for ‘abortions,’ stripping away bodily autonomy, furthering their oppression, and turning essential healthcare of desperate women into a criminal act.”

“As it stands, England and Wales have the most severe punishment for an illegal abortion in the world,” said Rachael Clarke, Chief of Staff at the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS). “This is worse than countries and states with severe anti-abortion laws such as Texas, Afghanistan, and South Sudan. We are on the wrong side of history.”

It would be tempting to think that 55 years after the 1967 Abortion Act allowed for the availability of safe, legal abortion in Britain (Northern Ireland was never included in the Act), women would be able to terminate an unwanted pregnancy free from fear of criminal prosecution, and from paternalistic laws that require the approval of two doctors.

In fact, freedom of information data obtained by The Dial suggests that the number of criminal investigations of alleged abortions in Britain has dramatically risen in recent years.

Between January 2021 and November 2023, 17 police forces in England and Wales had investigated a combined 33 allegations of unexplained pregnancy loss — compared to 67 investigations in the decade between 2012 and 2022. Six police forces did not respond to the freedom of information request, while 20 said they had not investigated illegal abortions in the specified timeframe. London’s Metropolitan police confirmed it had investigated people for allegedly administering drugs or instruments to procure or cause abortions, but did not give a figure.

“The growing awareness over recent years that abortion can be completed with pills, rather than always requiring surgery, may well have contributed to the worrying increase we are seeing in police requests relating to unexplained pregnancy loss,” said Louise McCudden, MSI Reproductive Choices’ U.K. Head of External Affairs. “In the past, these incidents were much less likely to raise suspicion.”

Between 1861, when the Offences Against the Person Act became law, and November 2022, three women in Britain were convicted of an illegal abortion, and two were given jail sentences. They include a 24-year-old who was imprisoned in 2015 for two years after taking abortion pills that she ordered online when she was 30 weeks pregnant. The court’s judge referenced her internet searches during his sentencing. A second woman, Sarah-Louise Catt, was sentenced to eight years in prison in 2012. A third case, involving a refugee woman who accessed pills, was given a non-custodial sentence in 2012.

In 2021, a 15-year-old girl endured a “digital strip search” following pregnancy loss at 28-weeks. She was forced to hand over her text message and search engine history as police tried to prove she had taken abortion pills illegally. The process had a profound impact on the teenager’s mental health, before a coroner eventually ruled the pregnancy ended through natural causes.

Earlier this month, Bethany Cox, 22, was found not guilty after being prosecuted for using drugs to bring about an illegal abortion during the coronavirus pandemic. Prosecutors offered “no evidence” that Cox had taken drugs to induce an abortion, and admitted “evidential difficulties” in the case — something which her barrister Sir Nicholas Lumley described in a statement as an “extraordinary state of affairs.”

Rachael Clarke said she and BPAS “welcomed” the withdrawal of charges against Cox. “We are delighted that this case will not proceed to an unnecessary and gruelling trial,” she said. “However, this case should never have got to this point. Six women have appeared in court over the last 12 months for ending their pregnancies under a cruel, outdated law that passed before women had the right to vote. Two women are already scheduled to be put on trial in 2024.”

Today, more women are being investigated for illegal abortions in Britain than ever before. At the same time, their browser histories, WhatsApp and Facebook messages, and phone records, are increasingly being used as evidence to pursue abortion prosecutions.

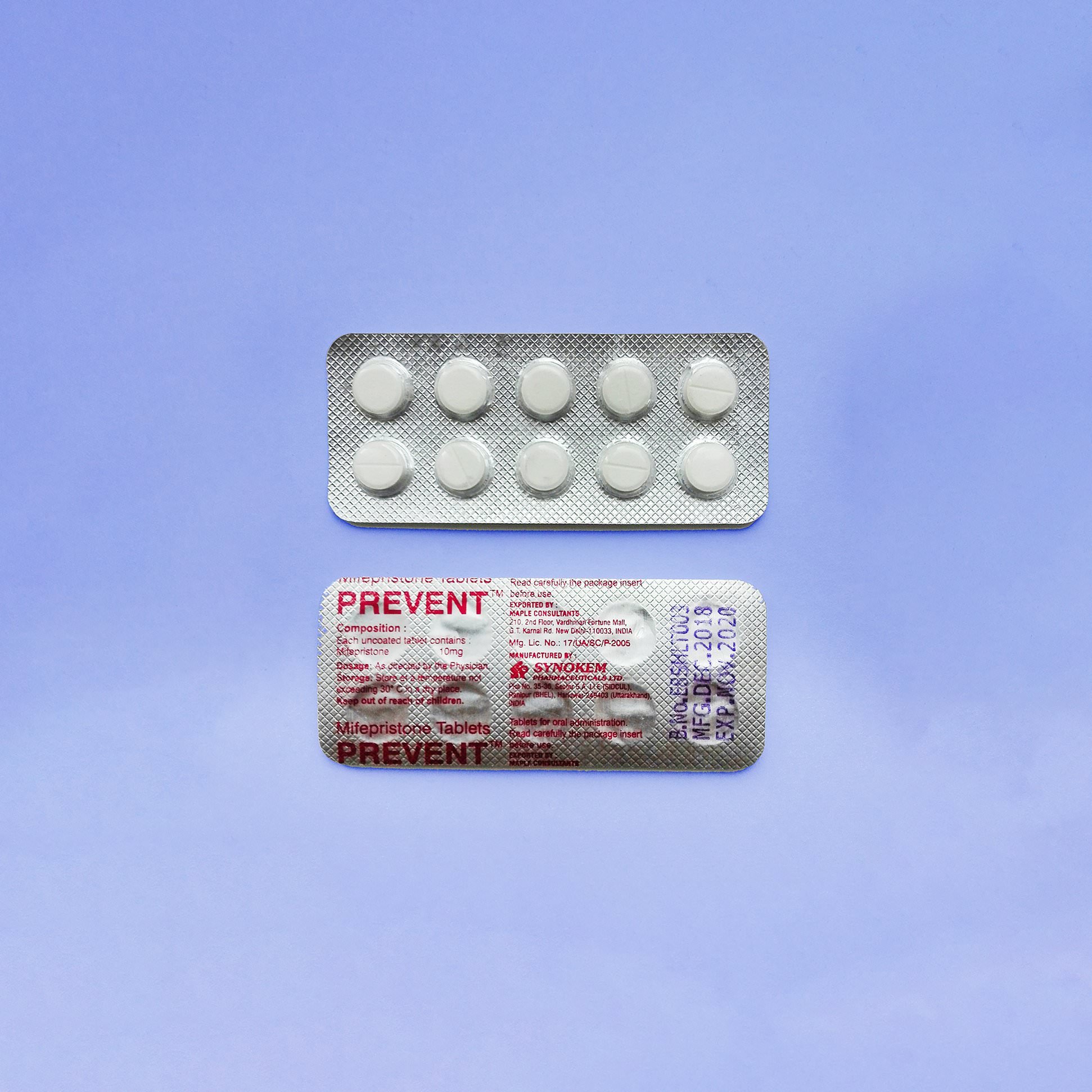

Foster is a mother of three and one of her children has disabilities. She was in a complicated relationship when she discovered she was pregnant, and was forced to move back in with an estranged partner who was not the father of the baby she was carrying. After searching online for information about abortions after 24-weeks, on May 6, 2020 she called the abortion provider BPAS and told them she was at an earlier stage in her pregnancy than she really was in order to access abortion pills.

The Foster case woke people up to the tenuous legal status of abortion in England and Wales and caused a media storm. Tabloid newspapers published photos of Foster leaving prison, and shared details about her relationships and mental health. The Daily Mail even spoke to her neighbors. In Parliament, MPs including the Conservative’s Sir Edward Leigh, Sir Robert Goodwill and Martin Vickers, as well as the Democratic Unionist Party’s Jim Shannon, used the case as an excuse to try and re-open a debate on further restricting abortion. They also called to end telemedicine (doctors can approve and prescribe women abortion pills to take in her own home following a telephone consultation), and to reduce the upper-time limit of abortion. To date, their efforts have not succeeded.

Today, more women are being investigated for illegal abortions in Britain than ever before. At the same time, their browser histories, WhatsApp and Facebook messages, and phone records, are increasingly being used as evidence to pursue abortion prosecutions.

Mara Clarke founded the Abortion Support Network, which helps women access safe abortion in countries where it is illegal. “We were once contacted by a U.K. police force investigating an unexplained pregnancy loss and where the suspect had our charity’s contact number in her phone,” she told me. Clarke is also the founder of Supporting Abortions For Everyone (S.A.F.E), which supports women to access safe abortions.

Several of these cases suggest that even when women with unexplained pregnancy loss are found to have searched for legal content, such as information about Britain’s abortion laws, it can lead to potential prosecutions.

“There is no way to prove any behaviour or even intent from private search results and other personal data,” said Emma Gibson, Equality Now’s Global Coordinator for Universal Digital Rights and co-leader of the Alliance for Global Digital Rights (AUDRi). “It is more than just bad science, it is a baseless witch hunt with no credibility, and in no way warrants the rights violations that it entails.”

In Britain, police can get a search warrant to access an individual’s browsing history to see if they have been viewing illegal content. This evidence can then aid prosecutions of serious crimes. But several of these cases suggest that even when women with unexplained pregnancy loss are found to have searched for legal content, such as information about Britain’s abortion laws, it can lead to potential prosecutions. Gibson told me that Human Rights Watch and other non-governmental organisations have already documented the use of search results in prosecution cases against women seeking abortions, and that technology companies may not be able to ward them off.

“Women are now operating in a hostile environment where we are seeing a roll back on reproductive rights,” said Sarah Simms, a policy officer at Privacy International, a U.K. NGO specialising in protecting the right to privacy. “Law enforcement, as well as those against access to safe abortion, are increasingly trying to get access to this data or using data-exploitative tactics.”

✺

In 2023, following Foster’s conviction, the news website Tortoise reported that period tracking apps may also be used to police illegal abortions.

The Tortoise investigation claimed to find examples of forensic reports which included requests for “data related to menstruation tracking applications” although it did not give details of the cases themselves. Of the 17 police forces that told The Dial they had investigated cases of unexplained pregnancy loss, none said they had requested period-tracking app data. The Metropolitan Police did not respond to that specific question in a freedom of information request.

“Period tracking apps can be beneficial to assist with managing your sexual and reproductive health,” said Simms. “But part of the issue is that they have not been built with a privacy-by-design approach, which can lead to data being exploited by both governments for law enforcement purposes and companies for commercial gains.”If requested, period tracking apps may be obliged to share their data with law enforcement.

Flo is a U.S.-based period tracking app with 7.5 million U.K. users. While there is no evidence to suggest it has shared its data with law enforcement, its privacy policy allows for the possibility, stating: “We may also preserve or share some of your personal data in the following limited circumstances: In response to subpoenas, court orders, or legal processes, to the extent permitted and as required by applicable law (including to meet national security or law enforcement requirements).” Flo responded to the overruling of Roe v. Wade that ended the nationwide right to safe and legal abortion in the U.S. by launching an “anonymous mode” to protect user data.

“There is an accuracy concern here,” said Alexandrine Pirlot de Corbion, Director of Strategy at Privacy International. “Sometimes you fill in the information in your period tracking app, sometimes you forget.” The idea that information on these apps is always the true version of events and interpreted correctly is false, she said. “That information is then at risk of being used to make life-changing decisions about an individual.”

Anti-abortion groups have also launched their own period-tracking apps. FEMM Health is the brainchild of the World Youth Alliance, an anti-abortion organisation financially backed by the Chiaroscuro Foundation. Chiaroscuro is primarily funded by Sean Fieler, a prominent donor to U.S. conservative organisations.

Nearly half a million women are now sharing their sensitive reproductive health data with an anti-abortion organisation. If requested, that same data can be shared by FEMM with law enforcement. The company’s privacy policy states that FEMM Health “may only release Personally Identifiable or Personal Health Information to third parties: (1) to comply with valid legal requirements such as a law, regulation, search warrant, subpoena, or court order.” This means that users are “inherently at risk, not because the company itself will necessarily violate its terms and conditions, but because simply by existing they become an entity that can be subpoenaed for data and information,” said writer and tech expert Kyle Taylor. (Flo and FEMM Health did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

✺

Foster’s sentencing provoked growing demand from the public to decriminalise abortion in Britain. In November, Labour MP Stella Creasy proposed an amendment to a forthcoming Criminal Justice Bill that would decriminalise abortion by repealing elements of the Offences Against the Person Act. Doing so would bring the law in England and Wales in line with that of Northern Ireland. Her Labour colleague, Diana Johnson, has proposed a different amendment to the Bill, which would allow for the “removal of women from the criminal law related to abortion.”

While the majority of the British public supports a woman’s right to abortion — according to the British Social Attitudes Survey, 95 percent of respondents said they support abortion when the mother’s life is in danger, and 76 percent support a woman’s right to end an unwanted pregnancy — Creasy and Johnson face a Parliament that is disproportionately anti-abortion. In a Parliamentary vote in October 2022 to implement buffer zones around abortion clinics, to protect them from protests, 110, or around one in six, MPs voted “no.” The no votes included high-profile members of the U.K. Government, such as the then-Home Secretary Suella Braverman.

In the run-up to Foster’s sentencing, a letter signed by a range of maternal health experts urged Judge Pepperal not to put the mother of three in prison. In response, he wrote that, “if the medical profession considers that judges are wrong to imprison women who procure a late abortion outside the 24-week limit then it should lobby Parliament to change that law and not judges who are charged with the duty of applying the law”.

As he saw it, his role as a judge is to apply the law. If the law is wrong, that is for Parliament to change.