The Failure of International Law

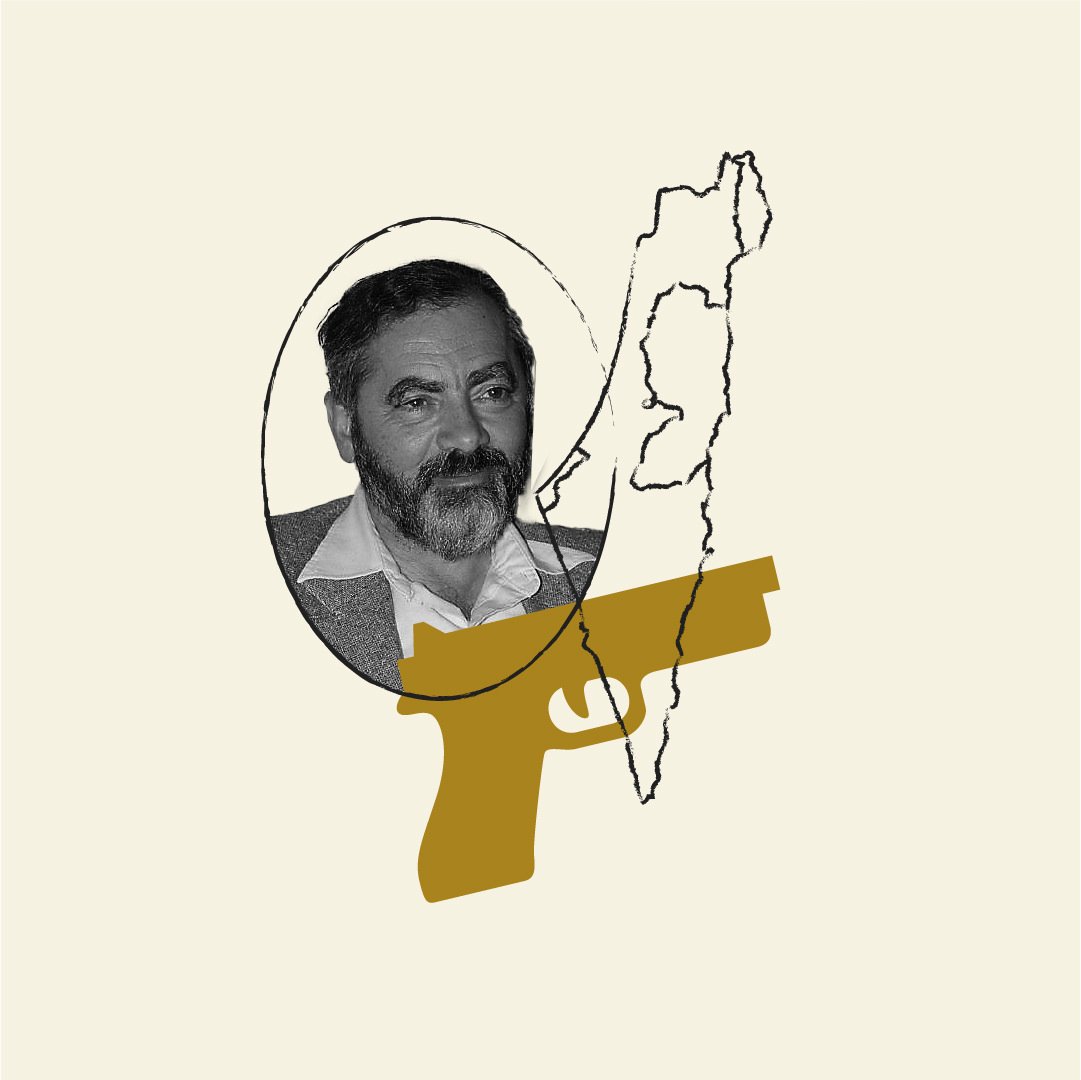

A conversation with legal scholar Itamar Mann about the war in Israel and Palestine.

OCTOBER 26, 2023

As the atrocities in Israel and Palestine have unfolded, human rights workers, lawyers, scholars, and civilians have looked to international law, and to the laws of war, for answers to the most basic questions: How could this have happened? How can we make it stop? Itamar Mann is an Israeli legal scholar who studies international law as it pertains to the rights of refugees and displaced peoples. He was at home in Haifa on October 7, and is now in London with his family. Mann spoke with Dial Executive Editor Linda Kinstler about how international law is operating in this moment, and how law might be wielded to break the cycle of vengeance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Linda Kinstler: What have the past two weeks been like for you?

Itamar Mann: My first response on October 7, was really a sense of enormous fear and outrage that this could happen. It felt like terrible negligence on the part of the military and the government. For decades the public sector, including government agencies that were supposed to provide run-of-the-mill security for citizens of Israel within the 1967 borders had dried up.

What we are seeing is the catastrophic unraveling of the endless occupation and siege on Gaza, coupled with the calamitous effects of the Israeli government’s defunding of the most basic services for citizens.

A rather famous case in point is the right wing government’s decision to deny protection for Israeli communities near the border with Gaza, which had to be overturned as “unreasonable” by the Supreme Court. But this also includes health, and really all needs associated with security writ large. It appears we now do not even have the thinnest night watchman state.

What we are seeing is the catastrophic unraveling of the endless occupation and siege on Gaza, coupled with the calamitous effects of the Israeli government’s defunding of the most basic services for citizens. The feeling is that negligence is so deep, and the decision makers we now have are so incompetent, that grave mistakes will be made on every turn of the road. There’s no one we can really rely on. Very quickly, civil society took action, and a lot of people are volunteering and giving assistance and help. But that only revealed further the deep sense that things were not provided for by the government.

As the days and weeks passed, that initial sense of dread started to fade, and instead a kind of realization settled, that life has changed in a very fundamental way. We were all walking on very thin ice, and that ice has broken, but we still don’t know what that means. Like many, I have been following the few hostages returning. And I have been deeply disturbed by civilian casualties in Gaza and the humanitarian crisis developing there.

LK: What were the things that the Israeli government defunded? What were the things that they didn’t provide?

IM: It was very clear that there is a lack of equipment for the purposes of taking care of wounded people, a shortage of mental health support, and significantly, a shortage of reliable information.

Living in the north of Israel, in Haifa, the main fear is a war with Hezbollah. In Haifa, there are petrochemical industries that have been there since British Mandate time. I think the fact that they are still there, at the center of a metropolitan area, also contributes to the feeling of gross negligence around basic security. It’s very well known that if these facilities are targeted by Hezbollah, the blast will create enormous civilian casualties and a kind of petrochemical mushroom over the city. I contacted an individual who is in charge of this facility to understand whether we’re doing anything to prevent that kind of damage. She said, look, there’s nothing to do because we can’t move the materials now. They're too dangerous. And they will be dangerous anywhere. So where will we move them to?

LK: How have you been personally affected by the violence, if at all?

IM: I have not been personally affected by the violence, but Israel is a very small place, and nothing is really that far away. The family of a very close colleague of mine is from a kibbutz called Kfar Aza. It has been basically destroyed. Another colleague’s sister was killed there. Former students had friends at the rave at Kibutz Re’im.

What I did feel immediately is a certain change on campus. I believe we will continue to experience enormous transformations in terms of the level of free speech that is allowed for students and faculty. Arab Palestinian students in particular are being monitored for their activity on social media, and disciplinary ramifications that we have not seen before are quickly being introduced. The political ramifications are clear – under the guise of security, civil and political rights are being set aside. I have no doubt that this will influence my own academic life. The semester has not started, and the government has now postponed it. We are supposed to start in early December, but it is not clear if that will happen. When we do come back into the classroom, I think it will be clear that something very basic has changed in terms of our interactions. Some students will be coming back from reserve duty in the war. Others will be constantly suspected as siding with the enemy.

LK: Do you see international law operating anywhere here?

IM: When Biden made his first address on this conflict, he started by talking about the laws of war. I think he has a particular understanding of the laws of war, which is not characteristic of most professionals in this field around the world, but it is what is understood as the laws of war in the White House, in the Department of Defense, and the Pentagon. Generally, as applied to Israel, it appears in this case to be about providing some level of humanitarian aid, and perhaps about not starving people as a method of warfare or of pressure on Hamas. This is a very thin understanding of the laws of war to begin with. But it is what is relevant now.

Normally, we think of laws of war and international humanitarian law as kind of horizontally enforced among many parties that all accept the rules as binding, whether through treaty or custom. Here, it's basically a vertical relationship between Biden and Netanyahu, where Israel is a client state in the most bare and obvious way. Can you call that law, or is it just one party telling another party what to do because they have the power to do so? It's a philosophical question: even in the most basic tradition in which law means enforceable command, that command must be general. So I think the answer is probably no, that’s not really what we talk about when we talk about law.

There seems to be a hope among certain lawyers that this time international criminal courts will provide some form of accountability or deliverance or justice. Or maybe the hope is that domestic courts will ultimately take the lead through universal criminal jurisdiction. I have to say, I do not see that happening, and am not sure the impetus to double down is warranted.

And yet, there may be certain limitations on what Israel can do in this war that are imposed because of the hierarchy of power. They’re very meager, and they’re probably not enough. The momentous violence Israel has already imposed upon Gaza, and the quickly increasing death toll in the thousands, is the result of very well-articulated and very public calls for revenge and for exerting enormous damage, damage for damage’s sake. But maybe, I don’t know, there is still something here that would be different if Israel was getting U.S. aid without any strings attached whatsoever. The strings are minimal, but they are identifiable.

What’s also clear here, and this is somewhat related, is that the whole myth of a strong Israeli army, or Israeli military sovereignty, all of that has proven to be completely illusory.

LK: Is there any chance that law, in whatever form, might be enforced in this conflict, or has it been rendered completely impotent?

IM: I’ll start from law as applied to Israeli military action. The Center for Constitutional Rights, an American nonprofit, published a legal opinion about Israel committing the crime of genocide, which, if that proves to be the case, would provide for forms of enforcement that are beyond the International Criminal Court. The International Court of Justice in the Hague also has jurisdiction when it comes to the Genocide Convention . But I personally think that those forums of public international law are at this stage utterly irrelevant. Various parties, including Palestinian actors, and including the Israeli NGO Public Committee Against Torture, have attempted to hold Israel accountable at the ICC. But this campaign has been going on for an extremely long time. Over the years, I’ve become more jaded about that possibility.

Now, when some Israeli politicians are saying very openly that it's either us or them, that we need to destroy them for us to be able to survive, there is also this renewed doubling down on categories from international criminal law. There seems to be a hope among certain lawyers that this time international criminal courts will provide some form of accountability or deliverance or justice. Or maybe the hope is that domestic courts will ultimately take the lead through universal criminal jurisdiction. I have to say, I do not see that happening, and am not sure the impetus to double down is warranted.

There is a certain limitation of the imagination, in saying that this time it’s really the worst and therefore this time international criminal law will be useful. If there’s any chance that there will be a different dynamic at the ICC, it’s not because of Israel’s more extreme violence in this case, but because there was also extreme violence perpetrated by Hamas. If Hamas perpetrators of this extreme violence are also held accountable, and there is a kind of “balanced” approach that can now be taken, that may make it a little more politically possible for the ICC to play a role. But even that is highly unlikely.

Perhaps the more innovative avenue has to do with limitations on arms sales to Israel under domestic law. I have seen that the Palestinian human rights organization Al-Haq together with the Global Legal Action Network have published a briefing in that direction. I’m not entirely convinced that will be effective, but am more able to see the political and movement-building value of the exercise.

LK: You have remarked elsewhere that the rush to make genocide accusations on both sides signals the utter failure of international law. How do you view that failure, as both a scholar and practitioner? We are facing down the prospect of immediate mass killings, and the public has few mechanisms to combat it, other than, as you have noted, signing a petition, drafting a declaration, things of that nature.

IM: I am extremely worried that what we are seeing is, as you say, the prospect of immediate mass killing, that is already taking place, but also will continue in great numbers, and there’s basically nothing that can really stop it. It seems to me that the train has already left the station. The speed may vary, but the movement is there. This is a deeply depressing conclusion, that it is basically too late and there’s nothing left to do. One question one might ask is, what could have been done differently?

I think that the U.S. government, as well as other Western governments have turned a blind eye to the occupation for much too long, and are complicit with what we’re seeing now. The underlying basic, structural cause of all the violence that we’re seeing is reducible to the fact that the Palestinians have been subjected to indeterminate occupation, and in Gaza, also a kind of 16-year siege. These have amounted to one system of apartheid, with elements within Israel, and have been essentially dehumanizing. But foreign governments, including Arab governments, were happy to look away as long as dehumanization did not burst into the kind of spectacular violence we have seen since October 7. It is indeed in this context that we have seen dehumanizing attacks against Israelis.

There were many moments in which red lines could have been drawn and were not drawn. I don’t mean to take away responsibility from Israeli actors at all. I think that we are to blame for the development of a system of apartheid. Our government is the primary party responsible for this. But other governments could have done much more. Once again, not only the US but also Arab governments, which signed the Abraham Accords from a position of complacency.

An exchange of hostages and prisoners and a ceasefire are badly needed. But I just think the chances are extremely slim. Within Israel, this would be perceived as a victory for Hamas. What is clear to me is that domestic politics in the U.S., and domestic politics in other countries around the world that have interests in this issue, are more important in reaching a ceasefire than any public international institution, by far.

Both Israelis and Palestinians have already suffered terrible, terrible losses. To have a halt here, even one that is imposed by external actors in an effective way that would also ensure security for Israelis, would be better than following this road into an abyss that we can only imagine right now. I'm extremely afraid that, if we don’t stop and this develops into a ground incursion into Gaza alongside some kind of war of attrition in the North of Israel against Hezbollah, one of the sides will make a mistake. If one of the sides makes a mistake in this war of attrition — and we’ve already seen some mistakes but they can happen again, and in a big way — the outcomes are very uncertain and extremely risky. The only thing that I can see as potentially stopping scenarios of extreme risk for civilians in the region is the slight chance of an imposed ceasefire, perhaps facilitated in collaboration between the US and regional powers. All this is more about politics than about international law.

LK: What has it been like to see your colleagues abroad responding in very disparate ways to what’s going on?

IM: I’ve been associated with what, within Israel, is sometimes called the “radical left.” I don’t think in other contexts the positions of this camp are necessarily considered radical: support for a democracy that doesn’t have Jewish attributes, and instead is based on equality for all its citizens and social justice. Some of the positions I have seen from colleagues who are considered to be on the “left” abroad have led me — as well as many others in the Israeli left — to immediately feel entirely alienated from them. To be sure, I think these positions belong to a minority, but still one that has certain influence.

There is an interesting aspect of norms during warfare, or during revolution, that is revealed here. Does one side imagine members of the other side as potential members of the community it will establish after it will win the war?

Those who expressed the view that the massacre of October 7 was part of a decolonial campaign to liberate Palestine were the most disturbing. The underlying implication, sometimes explicit, sometimes implicit, has been that people who are considered settlers — not only people beyond the 1967 borders, but all Jewish Israelis within the area — are legitimate targets for the liberation war. Killing us is part of decolonizing the area, within what is referred to as a settler colonial paradigm.

Within the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, in our area and abroad, many have been more nuanced. Many Palestinians are now seeking measures against Israel and accountability for rampant killing by Israeli bombs, indeed making the argument on genocide, but are far from the implicit legitimation of the killing of Israelis. Those are messages I can understand and sometimes also endorse and support with all my heart. But regrettably, there was not enough clarity in the first days after the October 7 massacre, and a sense of sharing a struggle for liberation has been to some extent broken.

There is an interesting aspect of norms during warfare, or during revolution, that is revealed here. Does one side imagine the other side as potential members of the community it will establish after it will win the war? We might think of this as a kind of imagination of a social contract between rivals in war. Surely, Israel has failed that test time and time again when it comes to Palestinians. But the sense of a shared struggle was based on the agreement that a left position must imagine everyone as an equal member of a post-revolutionary society. Now we are seeing a different imagination being articulated, one perhaps based on a certain understanding of the Algerian revolution: that the “settlers” must leave, or die. Supporting such a position or even forming a certain coalition with it is totally out of the question.

LK: This war has already taken thousands of civilian lives. How have you observed this situation collapse, or rather critically endanger, the status of the civilian?

IM: Despite my pessimism about legal enforcement, I think legal principles might actually give us some guidance here. Among international lawyers, we say that civilians are not targetable unless they are “directly participating in hostilities” (DPH). And even if Israelis in many aspects of their civilian lives are quite militarized, we have rich and varied lives, like anyone else. We are of course not always directly participating. This is easy to say about a baby. But the same goes for an 18-year-old civilian, watching television in their home. They are not directly participating in hostilities. They should be entirely protected, and any suggestion to the contrary is fundamentally objectionable. For this purpose, it doesn’t really matter if they are located in occupied territory or in Israel proper.

Interestingly, DPH is arguably the category Israel and the U.S. have used to expand their ability to target civilians. This has been central in debates post-9/11. But this is mainly because just like any legal category, DPH can be abused if applied in bad faith. There is no reason to assume a-priori such bad faith. We should all be able to distinguish between civilians and combatants, even if we happen to think that the civilian is a “settler.” And we should all be able to distinguish between civilians and combatants, and refrain from collective punishment against civilian populations, for example through denying water, food, medicine, or electricity, as is happening in Gaza right now. Sharing such values, whether framed through international law, Shari’a, Jewish law, or any other doctrine, can be the basis for coalition across rival groups.

Another, perhaps deeper, critique of the civilian-combatant distinction in international law is that it often functions as a form of domination: only the stronger side can “afford” to make the distinction and win the moral high ground. The weak must use the weapons of the weak (and can therefore target and kill settler civilians). But that critique too must be rejected, if the weak mean to ultimately win the war and live alongside the party they had fought. The other option they have is to discard any such plan.

LK: You are describing the sense of extreme contingency in which everyone is living at this moment, defined at once by a dearth of reliable information, and also a desire to know everything as it happens. Is that the kind of Hobbesian panic terror that you said, on X, that you had experienced?

IM: For Hobbes, “panic terror” is when fear does not have reason or rationality attached to it, in which case people act in unreasonable and irrational ways, pushed by impulses. They end up running in different directions and doing all kinds of contradictory actions at the same time. I had been thinking about this in my academic work on refugees, in terms of the way that large-scale refugee crises sometimes occur, where people really don’t feel that they have any possibility to have any organized form of protection, so they just flee. My initial response to all of these events, on the emotional level was fear, a fear that's not attached to reason. I didn't feel that I could reason through how to act in a way that would stop the most catastrophic results. So in that regard, it’s very similar to panic terror.

It is now abundantly clear that Israel is using military force for the purposes of revenge.

Before we left for London, there was a ferry — a cruise ship, really — that the American Embassy provided for American citizens to leave from Haifa to Cyprus. I’m an American citizen, and we registered initially for that. I was standing with my family, in the Haifa port, waiting for the cruise ship to leave. I was extremely fearful, but I also was curious about this opportunity to do this unexpected participant-observer fieldwork in the context of maritime migration, which has been really important in my scholarship. We didn’t end up going on that ship – there was a lot of chaos. We ended up taking an El Al flight.

I think this feeling of panic terror is playing out differently in different parts of Israeli society. My friends who are Palestinian citizens of Israel have been displaced in similar ways. But their circumstances are also different, because they're also thinking of their own basic liberties in a context in which many fear that any Arab Palestinian will be suspicious immediately. There are people who have decided to leave because of that reason.

LK: I have been curious about calls to hold Hamas accountable, legally, for their crimes. I saw online that an American rabbi had said that Hamas leadership should be tried in the same way that Adolf Eichmann was tried in Israel. You have written extensively about the legacy of that proceeding and its implications for Israeli law and politics. What do you make of such calls?

IM: It is now abundantly clear that Israel is using military force for the purposes of revenge. You normally think of revenge as something that is lawless. But criminal law does give a certain refined version of revenge legitimacy within the system. The question came up in my mind: what would be the outcome, how would it play out, if an imaginary Israeli government would say, I'm not attacking the entirety of Gaza, I’m not going to go for revenge through military might, which is completely illegal under any understanding of the laws of war. But I will hunt these people down, and I will try to arrest them wherever they are, and I will bring them to trial, and perhaps even execute them if convicted (just like Eichmann was). Would that be better? Criminal law might give us a certain vocabulary, an outlet for these very, very strong feelings of revenge that exist in extremely large parts of Israeli society.

✺ Published in “Issue 9: Weapons” of The Dial

ITAMAR MANN is an Associate Professor at the University of Haifa, Faculty of Law. He researches in the areas of legal theory, international law, refugee law, and international criminal law. He has published in leading journals and edited volumes, and his book, Humanity at Sea: Maritime Migration and the Foundations of International Law, came out in 2016. Itamar’s recent scholarship has focused on law and oceans and seas, and on the law pertaining to boats — from rescue vessels to cruise ships. He is the president of Border Forensics.