Can Anyone Stop Paris From Drowning?

The city is preparing for the return of a hundred-year flood that could displace millions.

JULY 20, 2023

I.

In late 2019, trucks carrying Greek statues, Egyptian sarcophagi and sculptures by Bernini departed from the Louvre Museum in the center of Paris. Bound for Liévin, a small French town near the Belgian border, the artworks were wrapped in frames and stacked on pallets for the journey.

Liévin was not a well-known cultural capital. A former mining center, its most prominent public art was a sculpture commemorating a 1974 explosion that killed 42 workers. The trucks were heading to a low triangular building northeast of the city. Once unpacked, the artworks would be stored along a “boulevard” lined with doors 5 meters tall, either placed along 26 kilometers of hallways or hung up on mesh wiring. Ninety-six stone columns that had been raised out of a ditch along the rue de Rivoli were covered in plastic wrap and transported on wooden pallets to be unpacked in the northern town, near a small satellite of the museum.

After 16 months of to-ing and fro-ing, the trucks completed their mission: 100,000 artworks in the Louvre’s underground storage had been removed from Paris. The last time this kind of evacuation took place was the late 1930s, at the advent of the German occupation, when artworks were hidden away to the Château of Chambord. This time, the Louvre was preparing for another sort of catastrophe: the inevitable yet unpredictable flooding of the Seine.

The Paris region sits at the meeting of four rivers: the Seine, the Marne, the Oise and the Yonne. Visitors to the city tend to follow their eyes upward toward the city’s monuments and spires. But under the Eiffel Tower lies a vast water table. Streams course through the soil, cutting their own paths across the earth. The observant flâneur might notice that the name of the city’s hippest neighborhood, Le Marais, translates to “the marsh.” In the southeast of the city, small metal plaques mark the passage of a river called the Bièvre under the sidewalks; it was pushed underground in the early part of the 20th century. Under the Palais Garnier, with its paintings by Marc Chagall, is a 10,000 square meter artificial lake, which inspired Gaston Leroux to set his novel The Phantom of the Opera there. Now police and firefighters use it to practice scuba diving. French protestors used to shout, “Sous les pavés, la plage!” — “Under the cobblestones lies the beach!” They were almost correct. Deep underneath the roads of Paris there is not sand but pools of water.

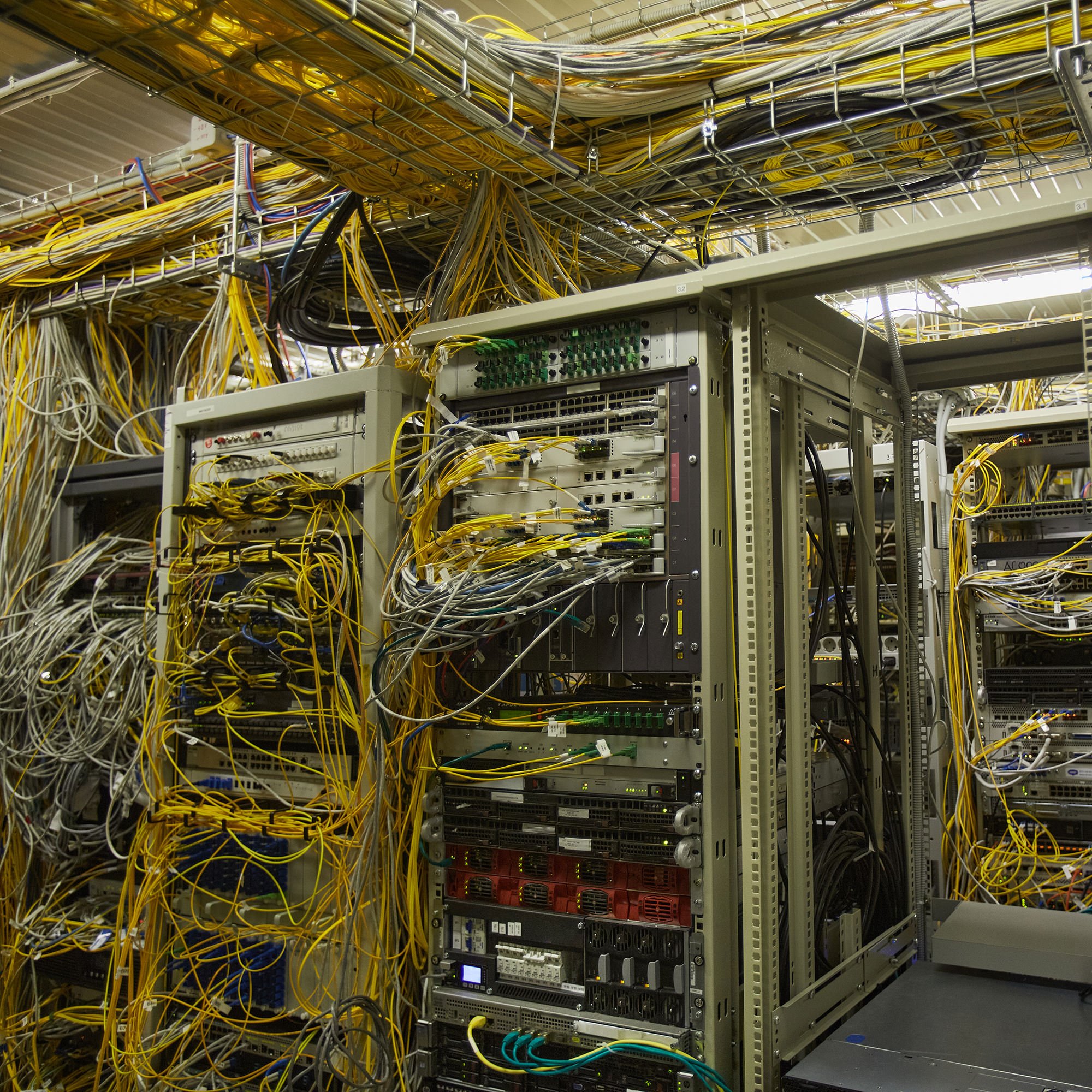

The chalky land is riven with holes; over the past century, it has been drilled and dug up and drilled again. Paris lies atop 217 kilometers of metros, 2,600 kilometers of sewers and 300 kilometers of catacombs; there are also conduits for water, telephone cables, electricity, and the new tunnels of what will be the Grand Paris Express, a planned subway system that will connect the city to its suburbs. Every year, the water threatens to rise up through these tunnels.

Unlike floods caused by storms or bad weather, rivers tend to rise and fall slowly; asynchronous with the water table, their movements are irregular and uncertain. Though scientists are currently working to create models of what the flood will look like and where it might flow, it is hard to predict where, and how much, water will pour into the streets. In 2017, construction workers in the northeast of Paris accidentally pierced through the water table, flooding the train system and halting traffic for days. The accident was a small example of what awaits in the case of a hundred-year flood, which could occur at almost any point. According to Serge Garrigues, a retired general once in charge of overseeing such disasters, “It could be that everything works fine. But if we end up in this kind of situation, all of a sudden, we might have a whole transportation network that collapses.”

II.

There’s reason to be worried. After all, Paris has flooded before. The last catastrophe to overtake Paris occurred about a hundred years ago, in 1910. It started in January, after a fall heavy with snow and rain. The river began to rush so fast that people upstream could not take accurate measurements of the swell. Paris depended on the Seine for deliveries of food and supplies, but the speed of the water moving along the banks prevented ships from docking.

An observer described how the city was full of “good humor,” momentarily transfixed by the oddity of it all. But the reality was frightening.

Then time stopped. A pneumatic system that pumped compressed air throughout the city, blowing through its postal system and animating the public clocks, was submerged. 5,800 clocks fixed the time at 10:33 p.m. on Jan. 21. The next morning, Parisians found that their basements had become inundated with water, which also came up through the maintenance holes and flowed into the streets. In her book Paris coule-t-il? (Is Paris drowning?), Magali Reghezza-Zitt describes how the telegraphs and telephones stopped working, as did the electricity and the heat. The city, which had only recently opened its metro system, was forced to rely upon carriages. Horses were taken out of retirement and housed in the Gare de Lyon, one of the few stations that did not flood and thus was transformed into a stable.

At first, people tried to carry on. Women lifted their skirts and waded through the rising waters. Soon that became impossible. Sailors arrived from Brittany with 300 dinghies; soldiers built bridges across avenues. Deputies rowed to the National Assembly in top hats. An observer described how the city was full of “good humor,” momentarily transfixed by the oddity of it all. But the reality was frightening. Paris was isolated from the rest of France. Without transportation barges, food sources were cut off, and existing stores were flooded, too. The city, which had just completed a sanitation system, could no longer operate its incinerators. Every day, 1,320 tons of trash were thrown back in the river. The garbage drifted downstream, polluting neighboring towns. The wooden tiles that covered the streets disintegrated and began to rot. Patients were evacuated from hospitals. In Ivry, southeast of Paris, a factory exploded.

“We can’t see where the evil is going to stop,” wrote one Parisian on Jan. 27. “The soldiers in the streets, the train carriages, the increase in the price of butter and eggs. A thousand little clues that you can’t perceive separately, but which together make up a particular atmosphere. You breathe it like air.”

The flood was not restricted to the flanks of the river. It seemed to travel everywhere. In front of the Gare Saint-Lazare, a mile north of the riverbed, the sidewalk groaned with water. One paper described how “the terraces of the great cafés which once sparkled with light and buzzed with movement are now deserted and black.” The slightest pressure of footsteps caused the asphalt to sink. “One has the distinct sensation,” the paper continued, that Paris was “tormented by both the waters flooding its surface and those bubbling beneath. It is threatened with sudden engulfment to unknown depths.”

The water subsided a week later, but it took until March 15 for it to fully recede. The nauseating, moist smell lingered weeks after the city had dried out.

III.

“It’s certain that there will be a major flood on the Seine, and it will be worse than 1910,” said Valérie November, who studies risk at the CNRS, the French national research consortium. In the past 100 years, the number of people in the Île-de-France region has nearly tripled. In that time, the risk for a major flood — more violent and lasting than the one a hundred years ago — has only increased, and small floods have become a regular part of Paris life.

In 2016, the Seine rose over 6 meters. Two years later, it rose nearly 6 meters again. Homes lost electricity; roads were cut off. Yet these floods are nothing compared with the projections for the hundred-year flood to come, which show the water rising over 8 1/2 meters, or more.

Current predictions say that a flood would affect nearly a million people, who will likely find themselves without lights or water.

The effects of climate change also mean that the flood is likely to be much larger and harder to track than its precedents. Scientific wisdom once held that flooding would occur in January after a rainy fall, as in 1910. But in 2016, the flood took place in May and June.

When the water arrives, it will knock out one of the densest metropolises in the world. In 1910, 150,000 people in Paris were affected, some 200,000 more in the suburbs. Current predictions say that a flood would affect nearly a million people, who will likely find themselves without lights or water. Without electricity, water treatment plants could stall. “In that case, it’s not 900,000 people who would have to be evacuated,” said Servane Gueben-Venière, a professor at Sciences Po. “It would be more like 5 million people. We can’t leave people without drinking water, electricity or a sewage system for days.”

Yet few Parisians know to expect this disaster. Despite the regularity of flooding in France’s capital, and the probability of a major flood in coming years, communication about it has been minimal. For a long time, the French approach has been to rely on the state, said Garrigues, the former general. Now government agencies have to get citizens to be more proactive about preparing themselves when the time comes. “That’s another big challenge.”

Over the course of my reporting, I looked up my own address on a government flood risk map. It told me what I had suspected but not fully known. The water is projected to reach the corner of my street. Who knows what will be happening in the basement. I’ll likely be out of electricity, possibly of fresh water, and without a sewage system. By law, I should have been informed of this. In practice, I had no idea.

IV.

On paper, the preparation plans look solid enough. Live in France long enough and you’ll know that for every eventuality, there’s a committee, a white paper and a scheme to follow — at least in theory. All institutions in the Paris region must submit to a bureaucratic jumble that is meant to assess how ready they are to face the water. There’s the PAPI ( an acronym that stands for “flood prevention action program”) and the PPRI (“flood risk prevention plan”) — as well as the PCA (“business continuity plan”) — all of which outline how cities and organizations will face natural risk. Paris’ flood plan, for example, details how nursing homes and hospitals must evacuate people in case of rising water, but does not provide specific guidance about where inhabitants might go. “Everyone has a continuity plan,” said Bruno Barroca, who studies urban resilience at Gustave Eiffel University, “but you can’t simulate how they might interfere with each other.”

The RATP, the city’s transportation authority, is particularly proud of its contingency plans. These go through David Courteille, a genial man whose official title is director of the equipment, stations and bridges business unit. He met me in his office in the Paris suburbs with a gift: a book on the ingenuity of the Paris metro. The organization has more than 700 people trained to protect at least 426 critical points of infrastructure when the time comes.

Still, the museum calculates that some 7,500 square meters of its exhibition rooms in Paris are vulnerable to flooding, including the collection of Islamic art.

Workers at the RATP must undergo a daylong flood preparation course that will allow them to be mobilized at moment’s notice. On a recent Friday, a group of seven employees was sitting on the RATP’s “campus” in a vast workshop surrounded by free-standing turnstiles and a large escalator. They were learning about what they might have to do when the flood arrives. The agency has requisitioned hotels so that workers could stay in central Paris without having to figure out a way home in the event of subway closures. The instructor passed around food packets of canned chicken and instant coffee, which he said had been based on army rations. The agency has been stocking up supplies, complete with little guides for putting together walls and barriers. At trainings, employees learn how to protect air vents (by covering them with concrete) and entrances (by creating double walls of sealed cement blocks). I watched them trade places so that each of them got a chance to practice mixing mortar and lining the bricks. “We know we’re going to screw up the sidewalks,” their trainer remarked.

Museums, too, have their plans. The Louvre has finished moving out artifacts from storage. Still, the museum calculates that some 7,500 square meters of its exhibition rooms in Paris are vulnerable to flooding, including the collection of Islamic art. The museum now runs exercises to see how quickly employees can evacuate the art upstairs and is working with engineers to figure out how to protect large sculptures that can’t be moved in tubes of plastic wrap. “There’s no perfect solution,” said Anne de Wallens, head of the museum’s Preventive Conservation Department, at a recent conference.

When the Quai Branly museum across the river was built in the early 2000s, the design incorporated the possibility of floods. The exhibition halls are raised on stilts, while the building is protected by an underground wall that surrounds it “like a cake mold,” according to Vincent Saporito, head of collections management. The hundreds of thousands of objects in the museum’s underground collections are organized by importance; 210 wheeled cabinets filled with masterpieces can be rolled upstairs in the event of a flood. Employees, he says, “are informed from the beginning about the particularities of our museum.”

But no single agency has full oversight of the Seine. The river runs through 14 different territorialities, each with its own administrative system. The dikes west of Paris are under different oversight from those to the east. Projects for new reservoirs have barely advanced. A new reservoir planned 100 kilometers southeast of Paris has been under consideration for three decades, but the project, regularly submitted for approval by local committees, has only advanced bit by bit. There is no certain date of completion. In any case, it would reduce the level of water in Paris by only a few dozen centimeters, according to Barroca. “People say, ‘Is it worth making a big dam for that?’”

Only 60 percent of towns in the Paris region have complied with the legal obligation to draw up local emergency plans. Fewer comply with the obligation to test these plans every five years, according to a report by the French government’s auditing body, the Cour des Comptes. Population density has steadily increased in flood-prone areas in the Paris region, the report continues, no doubt because flood protection plans have rarely been enforced. A coordination exercise in 2016 brought together local officials, network providers and firefighters to prepare for what will occur when the historic flood arrives. Nine hundred rescue personnel — made up of local firefighters and police and other state authorities from Belgium and Italy — simulated what they might do during the flood. They practiced evacuating a nursing home by helicopter and transferring victims by boat. At one point, they docked a boat by the side of the river and rifled through mounds of dirt with packs of dogs, who sniffed at colleagues lying in the mud to rescue them. A similar exercise will not be repeated until 2024. “It was very expensive,” said Ludovic Faytre, who studies risk at the Institut Paris Region.

In theory, during the flood, the Paris Defense Zone, which acts as a sort of intragovernmental emergency management system, will take over. But in practice, neighborhoods may be left to figure things out on their own. “A municipality will, for example, report its situation to the intermunicipality, which will report its situation to the departmental prefect, who will report to the department, then to the defense zone, which in turn will report to the interministerial crisis unit, if it’s activated,” said Gueben-Venière. “But by the time an answer arrives, there are already people making decisions on the ground.”

Reporting this article gave me a small taste of the kind of miscommunications that could arise when planning for, let alone being in the heat of, a crisis. The head of a European research organization tasked with flood research refused to talk to me before she received the go-ahead from the city of Paris. The city, claiming it had no authority over what a European organization should do, said it could neither approve nor disapprove. “People must know!” wrote the expert in the email. Still, she would not agree to an interview.

V.

One hot night in June, I went underground at the Gare Saint-Lazare to observe workers as they set up barriers at the entrance of the train station. Courteille’s team had just ordered some materials, and the staffers were working with a crew they had contracted to make sure the large grate they had commissioned would actually fit when it had to be deployed. We stood by the entrance to the metro, watching the final passengers exit. At 12:30 a.m., the workers began to assemble the barrier. A team of seven people unscrewed white panels along the side of the entrance to reveal joints and hooks. They carried large pieces of metal, molded with handles, and lined them in front of the entrance. A few rats ran by and disappeared into unknown holes. The workers continued, slotting in the aluminum panels one by one until they covered the entire wall. Within an hour, the entrance had been transformed into a reflective barricade to keep the water out. They paused briefly to admire their work, and then began to dismantle it.

The next morning, not a single piece of the flood barrier would remain. The only indication left would be a thin metal bar framing the entrance to the subway. Thousands of commuters would walk by it that morning, unaware that its dull reflection hinted at the threat to come.